The elevator doors snap shut behind Otto Solis and his fellow ironworkers. With a quick shudder, gears kick in for a rattling 90-second ascent through the concrete structure rising at the corner of Wilshire Boulevard and Figueroa Street in downtown Los Angeles.

The men huddle in the confined space. Wearing hard hats, bandannas, kneepads and gloves, they look like gladiators ready to fight.

It's the start of their 6:30 shift, a dark morning under drizzling skies at the construction site for the New Wilshire Grand hotel and office project.

Foreman Solis and his crew of 10 belong to a class of ironworkers known as rod busters. Their job today is on the 24th floor, where they will place steel that in three days will be encased in concrete, taking the structure up another story.

Consisting of small-diameter rods known as rebar, the steel provides strength to concrete, which would otherwise crack and crumble over time. Rebar is a crucial component of this skyscraper that at 1,100 feet will be the tallest building west of Chicago.

The central element of that skyscraper is the concrete structure, known as the core. It will house elevators and stairs and will eventually be surrounded by a skeleton of structural steel that will support the rest of the building.

The elevator jerks to a stop at the 19th level. The rod busters step onto a small platform and start climbing. Stairs, suspended from a deck nearly 30 feet overhead, sway in rhythm to their steps.

Their final ascent is up a series of ladders. Twelve rungs to the first deck, then 20 to the second, 12 to the third and 24 to the top level — the gantry — open to the sky.

Even with the concrete core standing just a third of its eventual height of 73 stories, the view is spectacular. To the northwest: the observatory at Griffith Park and the Hollywood sign. To the west where Ballona Creek reaches the sea: a small blue line of ocean, now obscured by squalls.

On Figueroa Street below, pedestrians with umbrellas move like dots on the sidewalks.

Solis and his men share the gantry with the concrete workers. Today the rod busters are on the east side, while concrete is poured on the west.

Rain falls harder as Solis puts on his tool belt: 15 pounds of equipment, including wrenches, tape measure, torpedo level, pry bar, pliers and a spool of annealed wire. He steps into his safety harness, straps wrapping over his shoulders, around his hips and groin.

He makes sure the lanyards extending from the harness are not tangled. When snapped onto the steel, these lines would catch him if he fell.

Twelve years ago, Solis was working maintenance for a McDonald's in Hollywood for $7.75 an hour. He had come to this country from Guatemala and never dreamed that in his first year as a rod buster he would make $36 an hour.

Today he has a home in La Puente, where he lives with his wife and three children.

“This is dangerous work,” he says, “but it can change your life.”

The rebar began its journey downtown from a Rancho Cucamonga scrap yard, owned by the Brazilian company Gerdau.

In the shadow of mountains, monstrous trucks haul piles of crushed steel — washing machines, lawn mowers, bottle caps, beer cans, watchbands and, on occasion, gun arsenals — to an electric furnace that at 3,000 degrees dissolves everything into liquid.

Amended with carbon, manganese, silicon and sulfur, the molten brew is cast and cooled into 20-foot-long billets, 6 inches square, which are then run through a series of rollers that shape it into 225-foot lengths of rebar.

Cut and bent, the rebar is stacked in a crosshatched pattern and wired together by hand to create three-dimensional checkerboard structures through which concrete can flow. The structures, averaging 3 feet deep, 8 feet wide and 19 feet tall, are known as cages.

Assembled in San Bernardino, cages are trucked to the construction site, stitched together on the ground to form even larger cages and lifted by a crane to the top of the concrete core.

Once the cages are positioned, steel plates are attached to their sides, and concrete is poured into the gap, enveloping the rebar. After the concrete hardens, the plates are removed. Every four days, a new story is added to the core.

Suspended midflight, the first cage sails over Solis and his men.

J.C. Cortez and Alvaro Reyes grab ropes hanging from either end of the structure and pull it into position. Thirty feet wide, it weighs 22,000 pounds.

“Cuidado con los dedos,” one man calls out. Watch your fingers.

“Esperese, viejo.” Hold on, old man, another teases.

Rod busters guide the cage to the top of one concrete wall, then climb on top, 300 feet above Figueroa Street, to unhook the lifting slings. Others begin anchoring the cage to the exposed rebar beneath it.

Clipping his lanyards onto the rebar, Solis joins them. With his feet braced against the steel, he cuts a 2-foot length of wire from the spool on his tool belt. He bends, twists and tugs it into a knot around two lengths of steel.

“Working with rebar is like a puzzle,” he says. “It's 1, 2, 3; not 1, 3, 2. You have to be methodical.”

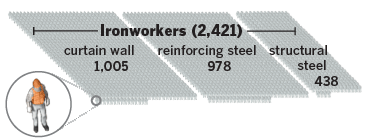

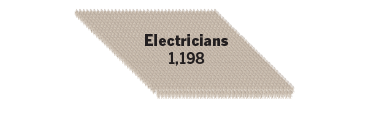

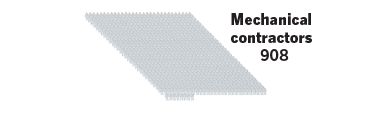

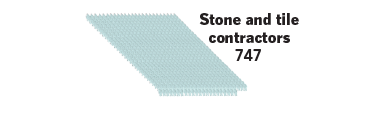

Nearly 400 workers are on the job at the New Wilshire Grand site, almost a third the number that will be there when the workforce peaks next December. They are ironworkers and the concrete gang, as well as carpenters, plumbers, electricians, glaziers and other specialists, each trade defined as much by ego and pride as by skill.

Racing toward an anticipated completion in 2017, the project is staffed six days a week for an average of two shifts a day.

Over the last year, the various crews have learned how to negotiate a site no bigger than a city block. Crowded with rebar, plywood, structural iron, scaffolding and machinery, the New Wilshire Grand is unusual among most construction sites because it offers so little room for storage or staging.

The number and flow of specialized workers from beginning to end

Each day, project managers oversee a carefully scripted schedule of truck deliveries and crane lifts for the immediate placement of materials.

“We knew that this job and this site would require patience and collaboration,” said Michael Marchesano, a general superintendent for Turner Construction Co. “We needed to get into a rhythm with one another.”

As of last week, that rhythm was being tested by a new phase of construction: the erection of the structural steel that will surround the concrete core.

Composed of beams, columns, braces and girders, the structural steel is massive. Some pieces, fabricated by Schuff Steel in Arizona, are nearly 40 feet long and weigh up to 51,000 pounds.

Made of special alloys, the steel is shipped from mills from around the world.

Steel from Germany is as thick as a phone book and prized for its resistance against peeling. Steel from Luxembourg is valued for its heft: Just 1 foot of one beam weighs 730 pounds.

Steel from South Korea was purchased in part as “a good faith gesture,” says Schuff project manager Jake Doherty. The New Wilshire Grand is owned by Korean Air.

The arrival of the structural steel also marks the arrival of the structural ironworkers, whose aerial feats balancing on beams high above streets in Manhattan and Chicago first inspired fear and awe nearly a century ago.

Last week, on their first day working the steel, Miah Thomas and Paul Graham performed a ballet 15 feet above a concrete deck.

With safety lanyards fastened beneath them, they walked a 7 1/2-inch-wide beam as if it were a sidewalk, spud wrenches hanging from their belts like swords. With wedges and crowbars, they aligned drill holes and bolted the beam into place.

“Being a structural ironworker,” says Chris Ahrens, a welder who watched the performance, “well, there is not much higher than that as far as being in the building trade.”

Unlike rod busters, structural crews are known for their swagger and an intensity that some argue come from the dangers of the work.

Eight U.S. ironworkers died in the first seven months of this year, three in July alone, according to the Iron Workers Union, a statistic that doesn't distinguish between rod busters and structural crews.

Major trades

Source: Turner Construction | Graphics reporting by Thomas Curwen

Structural crews have their rivals. Other trades view them as prima donnas whose willingness to take risks makes it easy to question their intelligence.

Round bolt, round hole, one carpenter said, as Thomas and Graham worked. How hard is that?

“Now being a carpenter, that takes brains,” he continued. “Most project managers began as carpenters. Jesus Christ was a carpenter. That's all I'm saying.”

Structural crews know they have a reputation as daredevils and hard partyers — and are trying to move beyond it.

“We cannot be viewed as the ‘crazy guys up there' and defined by 40-year-old movie stereotypes,” the union advises its membership in an article on its website. “We must replace myths and lies with the truth.”

Wary of outsiders, they avoid the limelight. Reality TV shows have courted them in vain, and the crew for the New Wilshire Grand turned down repeated interview requests from The Times.

“I learned to do as the old-timers taught me,” said foreman Craig Castor. “Keep your mouth shut and work hard.”

On the gantry, as the rain continues to fall, Johnny McCormack with the concrete company Conco gives the go-ahead to a pump operator working with the mixer trucks as they arrive off 7th Street.

From the pump, the mix flows through a 5-inch-diameter pipe across the construction site and up 300 feet to the gantry.

McCormack manipulates two toggles on a wireless remote control board hung around his waist. It directs the movement of a long robotic arm that holds a nozzle for dispensing the concrete.

Advances in construction methods have given concrete workers a role equal to that of the ironworkers, even if there is little glamour in concrete.

Thirty years ago, delivering concrete to such a height would have been impossible, but chemical breakthroughs have changed that.

Special additives introduce tiny air bubbles, which act like ball bearings to help the mixture's flow. Other chemicals make the concrete movable and cohesive like gelatin, and some put a negative electrical charge on the grains of cement so they don't stick together.

Making concrete is both a brutish and refined process.

Blasted out of the earth, limestone boulders are crushed and blended with calcium, silica, iron and alumina.

Pulverized into dust, the mixture is heated to more than 2,700 degrees, a process that melts and fuses ingredients into marble-size aggregations known as clinkers.

Ground down and blended with gypsum and more limestone, the mixture — now cement — is trucked from Mojave by its manufacturer, CalPortland, to a silo off Alameda Street.

When water and aggregate are added, the cement becomes concrete.

Balancing on top of a rebar wall, a worker positions the nozzle over a steel cage. The concrete drops with the sound of a coffee percolator. Two men snake electric vibrators through the rebar and into the mix, knocking out any air pockets.

If the concrete is poured too fast, it will place too much pressure on the steel walls and they will bow out. If poured too slowly, the concrete will start to set and not bond to the next layer.

Five passes will be needed to fill the western half of the core, a process that will take almost 10 hours.

A little before noon, Solis decides that the weather has become dangerous.

Wind gusts are clocking up to 20 knots, unsafe for flying steel, and satellite images of the storm show showers increasing for the rest of the day.

Solis halts the work. He had hoped to fly seven cages, but they managed just three.

The rod busters head to the ladders that will take them to the stairs and the elevator.

Solis stashes his tool belt in an equipment locker and grabs his lunch cooler.

They'll have to make up for lost time tomorrow.

Follow @tcurwen on Twitter.

Credits: Graphics reporting by Thomas Curwen | Graphics by Lorena Iñiguez Elebee and Len De Groot. Javier Zarracina and Jon Schleuss contributed to this report. | Production and design by Lily Mihalik