Stunned by the Watts riots, the L.A. Times struggled to make sense of the violence

Almost all of them are dead now.

When I joined The Times in 1970, they were the giants of the newsroom, still sharing the glow of the Pulitzer Prize for their coverage of the Watts riots five years earlier.

Forty-five years later, I looked back on how they told Los Angeles’ most tumultuous story of that era, and my first reaction was, “How could this coverage have won a Pulitzer Prize?”

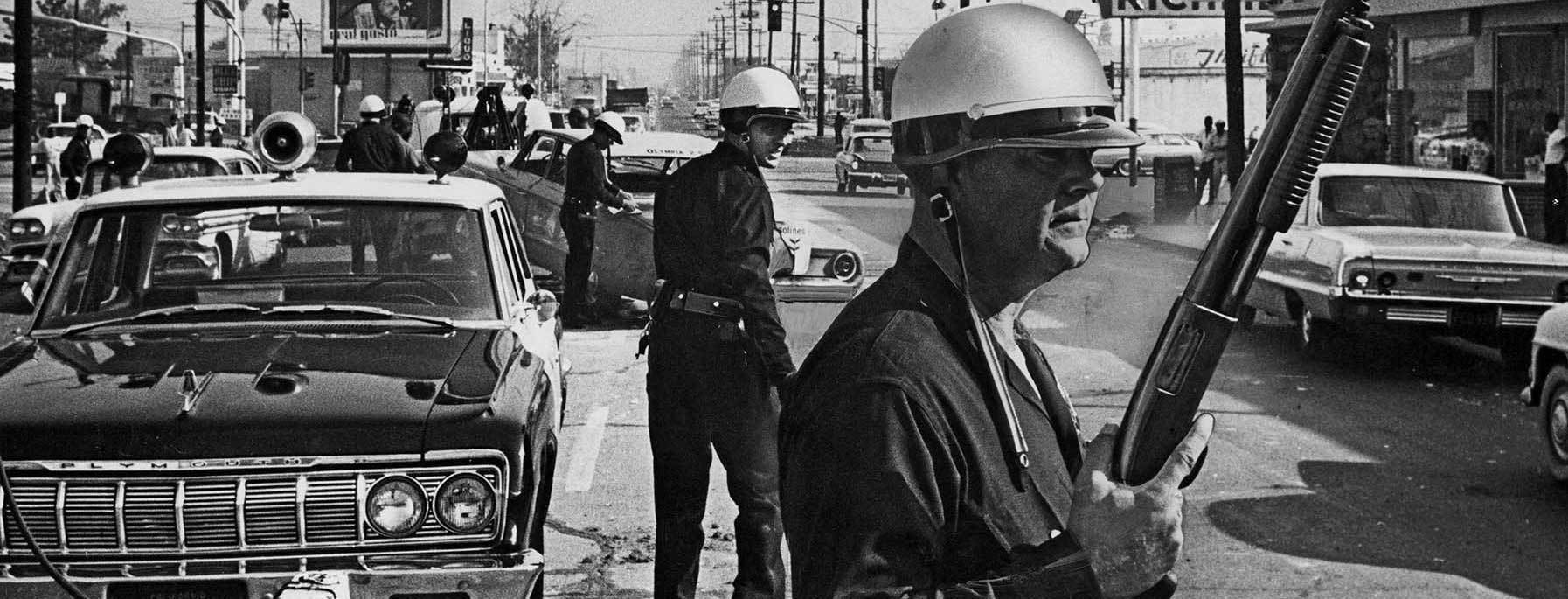

I'm not suggesting the work was unworthy. I read the stories with admiration for the reporters’ newswriting skill and for the courage of many white reporters who headed into the conflict zone.

But as the coverage continued day after day, it became apparent how unprepared these journalists were to probe the complex social currents that ignited and fueled the upheaval.

The race of rioters is not identified in any part of this story. It’s left for the reader to infer from the locations cited that the events are in the black part of the city and the rioters are most likely black. Click the highlighted selections to see them in context

Over the 11 days of riot coverage and initial follow-up, The Times’ perspective evolved from objectivity to alarm to befuddlement as reporters struggled to comprehend a threat to their city from the sort of racial conflict that until then had largely been limited to America’s southern and northeastern states.

I joined The Times soon enough after the riots to know that reporting of the time can’t be judged by the standard that applies to an incident today in Ferguson, Mo., or Baltimore or Oakland that sizzles instantly across Twitter, Instagram and Snapchat as fragments form an unfiltered kaleidoscope of perspectives. Back then, we used pay phones to call in what we saw and editors in the downtown office shaped it into a singular voice — the voice of white Los Angeles.

Still, as I read, I found it hard to digest the frequent use of “Negro.”

It’s easy to forget that the word was standard American usage in 1965. The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. had used it in his 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech, and the terms “black” or “Afro-American,” preferred by leaders such as Malcolm X, were just beginning to gain traction.

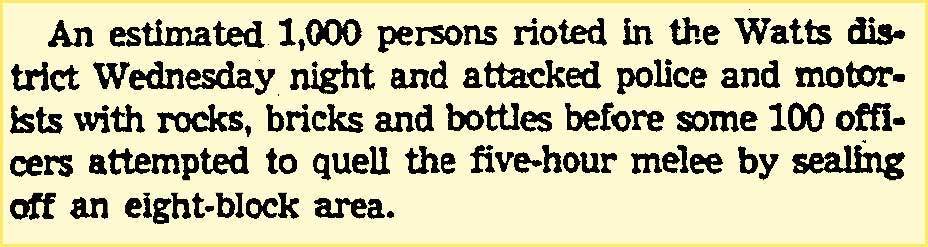

Yet, even then, there must have been some diffidence about the way the paper used the word. The first day’s key report began: “More than 1,000 persons rioted...” But as the days wore on, the term "Negro" became ubiquitous, used most troublingly as a collective noun: “the Negro.”

By the third day of rioting, the word “Negro” became synonymous with “rioter” on The Times’ pages. It was sprinkled through nearly every story, both as an adjective and a noun.

The first day’s coverage didn’t strive for answers, but rather offered simple, tight description of what reporters could verify at the time.

On the second day, the fumbling began.

Newsrooms had yet to fully develop the skeptical instincts that were later sharpened by the Watergate scandal, and The Times’ coverage wandered from the unchallenged invective of “the streets” to the unchallenged invective of two figures who would come to symbolize rigidity and repression: Mayor Sam Yorty and Police Chief William H. Parker.

The paper did offer a platform to black City Councilman Billy G. Mills as he called for a Human Relations Commission, but what he said was tepid — that the area’s “problems” could be “discussed.”

But in what would become a pattern of extremes and unbalance, it also let Parker deliver a front-page broadside on people “who have lost all respect for the law,” while two inside stories blared racial hatred from rioters.

Philip Fradkin, who would later bring the paper national stature as its first environmental reporter, wrote a harrowing tale of personally escaping mob violence. It included what can only be called a regrettable apologia for the police: “No officer I talked to, overheard or questioned ... made derogatory comments,” including using the N-word, regarding residents of the area, Fradkin reported.

The day’s most penetrating story was written by an unlikely team. Charles Hillinger, a jovial bear of a man who would later become the paper’s traveling chronicler of everything quirky in California, hit the streets to ask why the rioting had started. Veteran reporter Jack Jones, apparently writing from Hillinger’s notes, began the story: “Knots of Negro residents stood among the shattered glass residue of a hot August night’s violence on Avalon Blvd., Thursday night and their words were those of anger, frustration and resentment.”

The article dared to offer a resident’s view that the police themselves precipitated the rioting by dispatching dozens of cars to the initial flare-up. “If the police hadn’t come in like that, people wouldn’t all have come running out of their houses to see what was going on,” said resident Ovelmar Bradley.

But as the arson, looting and sniper fire intensified during a third day of rioting, that perspective was lost.

A Page One editorial set the tone by demanding “the sternest possible steps” now that “kid-glove measures have failed.”

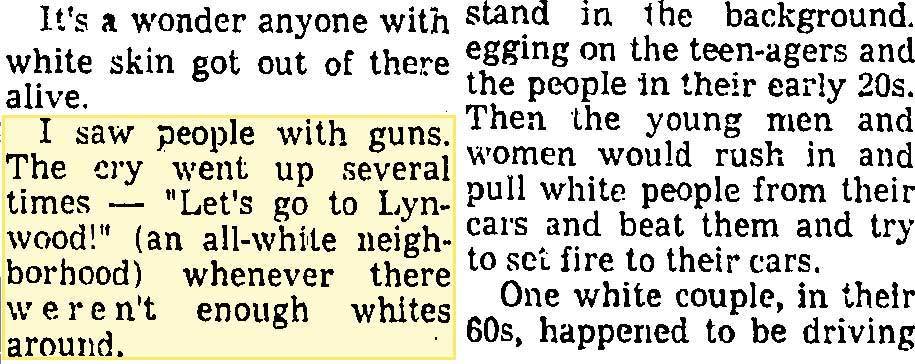

A first-hand account by a Times advertising salesman, who was black, was turned into provocative prose by a downtown rewrite man.

Richardson’s second eyewitness account produced the unforgettable slogan of the riots.

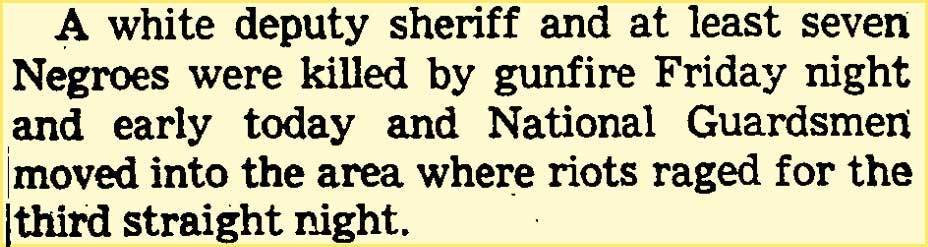

It pained me to read the day’s roundup under the byline of Art Berman, whom I later knew as one of the paper’s most sensitive editors. He too became trapped in the us vs. them, white-Negro dichotomy as the words “rioters” and “Negroes” blended into synonyms: “A white deputy sheriff and at least seven Negroes were killed by gunfire Friday night ... ”

That same day, a boldface note explained that Robert Richardson, a black advertising salesman for the paper, had volunteered to go into the riot zone — at once an admission that the paper had no black reporters and a false intimation that white reporters could not cover the unrest — they could and did.

Over the next two days, Richardson’s “eyewitness account,” rewritten in breathless prose by a reporter downtown, introduced the phrases “Get Whitey” and “Burn Baby Burn” and left the impression that black mobs were soon to be marauding through white neighborhoods.

A Page One dispatch from Washington cited Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s “The Negro Family — The Case for National Action” and quotes from President Lyndon Johnson, both asserting that the civil unrest could be traced to the disintegration of the black family.

Inside, Times medical writer Harry Nelson quoted psychiatrists who identified African Americans’ “feelings of rejection, self-hatred and anxiety about the future” as causes of the rioting.

Over the next few days, a flurry of one-source stories failed to challenge Parker and Yorty’s now obvious efforts to deflect responsibility for the continuing violence.

“Rejection and self-hatred” grossly misstate the more complex social analysis offered by a black psychiatrist later in the article.

One story proclaimed the area “totally devoid of effective community leadership,” echoing a quote from Parker that there was no reason to try to resolve the conflict in meetings because “these rioters do not have any leaders.”

Fifty years later, it’s unthinkable that reporters or editors would show such unskeptical deference to public officials, but later Times stories offered no counterpoint as Parker blamed Negro “pseudo-leaders” for “getting us into trouble” like “modern day Pied Pipers,” and Yorty blasted allegations of police brutality as “a big lie.“

A story without a byline allows Chief Parker to blame unnamed black leadership for fomenting the riot.

On the ninth day of coverage, as the rioting was subsiding, a fuming Yorty accused the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who had visited the smoldering streets of Watts, of “performing a great disservice to the people of Los Angeles and the nation” by suggesting that the riots could be partially attributed to police brutality.

King, who reportedly had remained calm while being berated by Yorty in a closed-door meeting, told reporters the next day that law and order could not be achieved “unless you have justice and human dignity in the community.”

After a meeting with the nation’s preeminent civil rights leader, The Times gives Mayor Yorty the forum to blast the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. as a provocateur.

On the 11th day of coverage, The Times finally pushes back on the harsh public comments of the mayor and police chief through the words of King.

After countless repetitions of the word “Negro,” it was a first for “dignity.”

King said he had not found Los Angeles’ leaders to possess the statesmanship and creative leadership to resolve the situation in South Los Angeles.

“What we find is a blind intransigence and ignorance of the tremendous social forces which are at work here.”

It was as if it took the visit of a true leader to shake The Times out of its confusion.

The next day National Editor Edwin O. Guthman, who had been a special assistant to Atty. Gen. Robert Kennedy and would become a mentor to me, wrote a richly thought out Op-Ed piece that compared the violence in Los Angeles to riots in Oxford, Miss.

“Each riot was rooted in deep and widely held resentments,” Guthman wrote. “Each was triggered by an official act and fanned by racial hatred.

“...We have all seen enough to know we must make it possible for whites and Negroes to live in a large city in peace and human dignity or this city and this nation are in for a very difficult and costly time.”

Two months after the riots, Times Editor Nick B. Williams tacitly acknowledged that the causes of the violence had not been adequately explored and launched a series to do so.

The “View From Watts” series quickly identifies basic inequalities in South L.A.

After 11 days of aimlessness, Guthman’s piece signaled a discernibly different course. As I read what followed, I began to understand the Pulitzer committee’s decision.

On Oct. 10, Times editor Nick B. Williams wrote a Page One editorial that acknowledged the paper’s failure to understand the riot’s causes, and pledged an “open and frank communication with the people of Watts, not just its leaders but the people themselves, including the rioters ... to explore the kind of thinking, the kind of passions, the kind of despair and apathy, that led to an explosion of hatred that rocked a great city and shocked the entire world.”

After Williams’ editorial, Jones returned to post-riot Watts to find 13 schools in that pre-federal lunch program era that lacked cafeterias.

“No one knows how many children in that poverty-ridden region find learning of little importance compared to hunger pains,” he wrote.

In another magazine-length story, he explored the resentment over lack of jobs, loan red-lining, bungled anti-poverty programs and educational failures that fueled the rage.

The story marked a dramatic improvement in the way The Times saw and shouldered its community role.

When I arrived at the paper five years later, Jones, who had previously chronicled mobsters and Hollywood scandal, had developed into a street-smart and sophisticated investigator of the black community’s daunting struggle to recover from upheaval.

Jack Jones’ lengthy analysis identifies a plethora of obstacles to solving the problems of South L.A.

That the paper had no black reporters to fill that role was a failure I still find hard to understand.

But with the benefit of 50 years’ hindsight, I can say confidently that the riots made The Times a better newspaper— and it seems obvious to me, at least, that this journalistic evolution was good for Los Angeles, as well.

Contact the reporter Doug Smith.

Design and Production: Lily Mihalik.