A Killer

on the Loose

Patients at UCLA were becoming deathly ill.

A superbug was spreading. Could doctors stop it?

A Killer

on the Loose

Patients at UCLA were becoming deathly ill.

A superbug was spreading. Could doctors stop it?

Doctors at UCLA’s flagship hospital were baffled: A healthy 40-year-old woman had fallen deathly ill after a routine procedure.

A long black scope had been threaded down her throat to treat troublesome gallstones. Now antibiotics were powerless to stop a raging infection.

Her physicians called in Dr. Zachary Rubin, the hospital’s director of clinical epidemiology and infection prevention, and its top disease detective.

He immediately suspected the scope itself — a dirty one could cause this kind of infection.

So Rubin inspected the hospital’s cleaning rooms, where workers scrub dozens of reusable medical instruments and load them in washing machines packed with powerful disinfectants. He saw no evidence to support his theory.

He considered taking the devices, known as duodenoscopes, out of service. But if his hunch was wrong, he knew there could be serious consequences.

The scopes, used several times a day at the hospital, save the lives of some critically ill patients and spare them complications from surgery. He held off to keep investigating.

But he didn’t realize that the woman wasn’t an isolated case. A superbug outbreak was already spreading inside UCLA on that day in mid-December.

A killer was on the loose.

--

The bacteria arrived at UCLA unnoticed in September, hitching a ride on a patient.

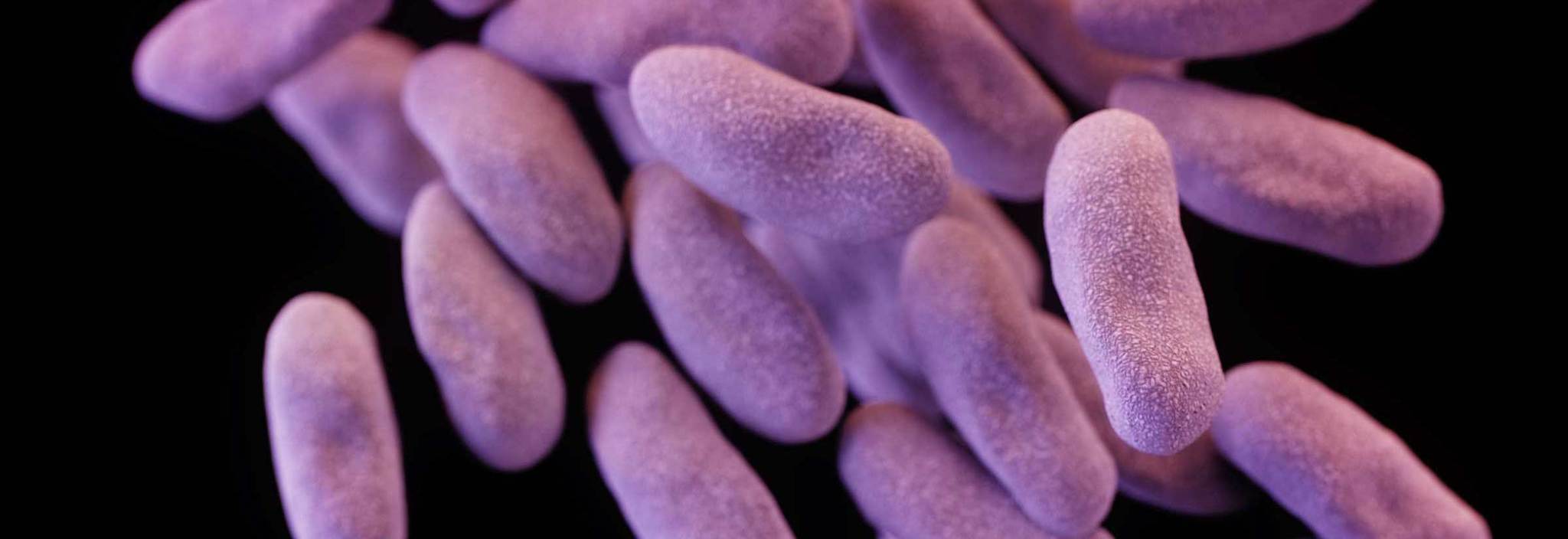

Unbeknownst to doctors, that patient — a woman being evaluated for a liver transplant — was carrying an unusually potent version of CRE, or carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae.

Some Americans carry these bacteria with no ill effects, but years of antibiotic overuse have created virulent strains immune to most treatments. By some estimates, CRE kills up to half of infected patients.

The source patient at UCLA underwent a procedure Oct. 3 known as ERCP, or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. During the procedure, a flexible scope is used to diagnose and treat problems in the digestive tract such as cancers and blockages in the bile duct. Nearly 700,000 such procedures are performed annually in the U.S. More than 800 are done each year at UCLA, among the most at any hospital nationwide.

The medical scope had picked up the bacteria from the woman’s intestinal tract, and the standard cleaning didn’t remove it.

--

Just two weeks later, in mid-October, Lori Smith called 911 at her modest home in a leafy section of Woodland Hills. Her 18-year-old son, Aaron Young, was doubled over in pain. He couldn’t summon the strength to get dressed after his morning shower.

Young landed in the pediatric intensive-care unit at UCLA with an inflamed pancreas. Four days later, a doctor guided a slender scope down his throat to put a tiny stent deep in his gut.

It was the same scope that had been used earlier on the first CRE patient.

Within days, an infection sent Young into septic shock. As his fever hit 104, nurses piled green cooling blankets on his 140-pound body. A ventilator kept him breathing.

Doctors soon realized he was fighting an antibiotic-resistant superbug. But they had no idea where it came from.

His parents — Lori and her husband, Glenn Smith — struggled through each day, not knowing whether their son would survive another night. They took turns sleeping on a small couch pushed up against the wall of his fifth-floor room in the ICU.

On her mornings at home, Lori Smith would check her son’s latest lab results on her smartphone.

“Every day brought a new horror,” she said.

The nonstop fever and the cooling blankets, set to 30 degrees, kept Young shivering uncontrollably. His body began shutting down from an untreatable nightmare.

--

As Rubin focused on the 40-year-old woman dying in the ICU several weeks later, he wasn’t yet aware of Young’s predicament — or the patient who first carried the superbug into the hospital.

He ordered his 10-member team to pull the chart of every CRE patient at UCLA in the previous year.

Rubin wanted to know whether infected patients had other things in common. Were they hospitalized on the same floor? Did they undergo a common procedure?

The medical records turned up 34 patients, including Young, with a CRE infection. But about half of them had CRE before coming to UCLA.

Rubin and Dr. Romney Humphries, the microbiology lab chief, agreed to search back even further and pull samples from every CRE patient since 2011. The samples were stored in a freezer at a UCLA lab a few miles from campus.

A bright orange biohazard sticker was stamped on the gray metal freezer in the back of the cramped lab. Humphries and two of her colleagues picked through long boxes covered in ice crystals that held the frozen vials.

Young’s doctors were experimenting with a cocktail of half a dozen antibiotics to fight his stubborn bacteria. One older drug appeared to work, but it posed severe side effects.

Young spent Christmas in the hospital. He was well enough to attend the hospital’s holiday party, decorated with a "Frozen" movie theme. One of his doctors took off his wristwatch and gave it to Young as a gift.

By New Year’s Day, he had turned a corner. On Jan. 6, Young went home after 83 days in the hospital.

--

Rubin’s detective work dragged on. Well into January, he still had not found the source of the outbreak — or whether he even had one.

The physicians using these scopes weren’t seeing a pattern either.

Dr. Raman Muthusamy, director of UCLA’s endoscopy lab, performed ERCP procedures on some of the patients who developed strong drug-resistant CRE infections. But the lab reports Muthusamy saw suggested they were different strains.

Rubin, standing at his desk, stared at a spreadsheet listing dozens of facts and figures on every infected patient. Nothing jumped out.

Rubin had the training for this. The Phoenix native, 41, once worked at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, researching surgical infections and the spread of the MRSA superbug. He had a medical degree from the University of Arizona and had done his residency at New York’s Mount Sinai Hospital before joining UCLA a decade ago.

But his experience wasn’t helping. An infection was stalking his patients and he didn’t know why.

At night, after tucking in his three children, Rubin dashed out for five-mile runs in his Westside neighborhood.

He picked over the clues in his head, asking himself: “What am I missing here?”

--

On Jan. 25, Young was due back at the hospital for another ERCP procedure to remove his stent. He was scheduled to go home five days later.

A doctor put a duodenoscope down Young’s throat for a second time.

“They said it would be a walk in the park,” said his father, Glenn Smith, a 53-year-old cabinetmaker.

Young crashed again. His temperature spiked to 103. His blood pressure plunged to 60 over 29. His survival was back in doubt.

On the same day Young was scoped, Jan. 27, Rubin and his team started to connect the dots.

The microbiologists had obtained a detailed genetic fingerprint for one of the CRE cases, and they confirmed that several infected patients were matches. It was only the second time that strain of CRE had been found in the U.S.

More conventional testing methods, such as looking at levels of antibiotic resistance, had given doctors the false impression that patient infections were unrelated. Tiny pieces of DNA were carrying an antibiotic-resistant gene from one cell to another, creating different-looking bugs.

With a cluster of matching cases, Rubin asked a young infectious diseases doctor to look back at when those patients had undergone their scope procedures.

Quen Cheng, on a two-week rotation in infection prevention, dug through computer files at his kitchen table at night.

Rubin was home nursing a bad cold the next day, Jan. 28, when his top deputy texted, telling him to check his email.

He opened a message from Cheng containing a hand-drawn diagram mapping out when every infected patient had been scoped. Cheng scribbled stars across the page showing each person’s superbug encounter.

“This is it,” Rubin said, sitting up in bed and staring at his laptop.

Now he had no doubt. The bug came from dirty scopes.

--

The discovery unleashed a chain reaction inside and outside UCLA.

Doctors had confirmed that the transplant patient, admitted four months earlier in September, had passed the bug onto a scope made by Olympus Corp.

Sitting on the edge of his bed, Rubin called the endoscopy lab and halted ERCP procedures. Next, he alerted L.A. County public health authorities.

The hospital pulled the cleaning logs to determine what scopes were used on the infected patients. Rubin needed a list of all patients who may have been exposed, so they could be notified for testing.

One scope, labeled No. 47, was used on most of the infected patients, including the one who brought the bacteria into the hospital in September — and Young. Another dirty scope, No. 26, was used on some of them.

Both scopes had been cleaned in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, federal and county health officials said. The $40,000 scopes were just 7 months old.

One of Young’s doctors, Jaime Deville, took his parents down the hospital hallway on Feb. 2 to tell them the news. He swallowed hard and braced himself for the yelling.

Young’s parents, overwhelmed by the information, were speechless. All they could do was return to their son’s room and pray over him at his bedside.

“The anger came later,” Lori Smith said.

--

The public learned of the UCLA outbreak when The Times broke the news on Feb. 18. In all, eight patients had been infected by the contaminated scopes, and three of them died. Nearly 180 other patients were exposed and advised to get tested.

The incident prompted the FDA to issue a safety alert to all U.S. hospitals the next morning, Feb. 19, warning them to take extra caution when cleaning the scopes.

That afternoon at a hastily called news conference, Rubin stepped up to the microphone in his white medical coat to address a row of TV cameras. He squinted into the afternoon sun and apologized to the superbug victims: “Our heart goes out to the people involved who passed away because of this infection.”

Reporters peppered him with questions about why it took so long to crack the case. Rubin calmly defended his work.

“We are seeing a greater number of these CRE bacteria in the community and patients coming here,” he said into the cameras. “It took additional detective work.”

Back inside the hospital, Rubin felt sick to his stomach. The chief executive of the UCLA hospitals tried to comfort him.

“This is a terrible situation for the patients,” then-CEO David Feinberg told him. “But we have actually saved lives here. We put this on the national stage. This is not just a UCLA problem.”

--

U.S. hospitals received new cleaning instructions for duodenoscopes a month later, in March, from the leading manufacturer, Olympus, which controls 85% of the market. The company also recommended a new cleaning brush.

Olympus had taken similar steps more than two years earlier, in Europe. The company warned European hospitals and doctors in January 2013 that lethal bacteria could become trapped at the tip of its scopes. It had issued no warning in the U.S., however.

Federal prosecutors have issued subpoenas to Olympus and two other scope makers, seeking details about when they knew about the dangers of their devices and what actions they took to safeguard patients.

After investigating previous outbreaks and receiving injury reports, U.S. health officials also were aware of an infection risk from contaminated scopes and had been working on new cleaning standards since 2011.

“It’s just shocking that so many people were affected by this without anything being done about it,” said Lori Smith, Young’s mother and herself a nurse. “Does business go on as normal and people keep getting infected?”

Food and Drug Administration officials counter that it took time to evaluate the evidence and develop a response to a complex problem.

Several UCLA patients or their families are suing Olympus for negligence and fraud in state court. Among them are Young and his parents.

Olympus declined to comment on the pending litigation. The company said it expresses “sympathy to the patients who have experienced infections and to their families. We are taking this matter extremely seriously.”

--

Young went home April 3, after 67 days in his second stint in the hospital. He celebrated Easter Sunday with family over a meal of prime rib and baked potato.

But he was back in the hospital 10 days later. His left foot was swollen, warm to the touch. Doctors suspected that the superbug had spread into his bones, but tests were inconclusive. They prescribed another 60-day course of antibiotics and, after several days, sent him home.

This might be his life for some time to come — never fully free of the dangerous bacteria.

Every subsequent surgery or procedure runs the risk of stirring up the superbug, and there’s no guarantee past treatments will rescue him the next time.

Young is one of seven children Lori Smith has adopted. The 57-year-old lost one son, James, to a heart condition when he was 10. Her eyes well up with tears when she considers what the future may hold.

“Aaron’s life has changed forever,” she said. “It’s hard to see a kid suffer.”

On a weekday evening at the family’s home, Young gathered enough strength to answer the door.

He wore baggy blue jeans and a dark blue T-shirt over his 5-foot-5 frame. A small smile revealed his braces. He sat down and fiddled with a small tube running from the catheter in his chest to the IV infusion pouch slung over his shoulder.

He spoke in whispers, punctuated by long pauses.

Young yearns to return to high school and see his friends again. He’s made plans to get baptized by his longtime pastor.

“All this tells me it’s time,” he said. “I thought I was going to die.”

--

The FDA summoned Rubin to its headquarters outside Washington in May for a two-day hearing about the scope-related outbreaks.

Olympus declined to participate. A North Carolina woman who lost her husband to a contaminated Olympus scope sobbed in front of the panel of medical experts and lashed out at the company and the FDA, accusing them of letting patients die.

Rubin flipped through PowerPoint slides describing the UCLA outbreak. Young was labeled Patient B on several charts.

The doctor outlined steps UCLA had taken to prevent future infections, but there is still no consensus about how to effectively clean these instruments.

After two days of testimony, the medical experts determined that the duodenoscopes were unsafe. But they said the devices shouldn’t be pulled off the market because they are used in a potentially life-saving procedure with no better alternative.

FDA officials are weighing their next steps. A redesign of the duodenoscope isn’t expected anytime soon. Meanwhile, UCLA and other hospitals have ordered more Olympus scopes — because new cleaning methods take the devices out of service longer.

In his ninth-floor office overlooking the hospital, Rubin is tracking UCLA patients who were exposed to the tainted scopes and checking for any new infections.

The outbreak makes him wonder what other medical devices touted by companies and cleared by regulators pose a similar danger.

“You realize — wait a second, what else are we missing here? These infections have been going on for years and people have known about it," he said. "My trust has been shaken.”

Timeline

Recent events involving scope-related outbreaks of antibiotic-resistant superbug infections at hospitals, including UCLA's Ronald Reagan Medical Center.

2013

January Scope maker Olympus Corp. issues "important safety advice" in Europe for the TJF-Q180V duodenoscope after infections at a Netherlands hospital. There's no notification in the U.S. Read more »

November Olympus visits a Seattle hospital to investigate a suspected outbreak. Read more »

2014

August Olympus sends a second safety alert in Europe after receiving complaints about tainted scopes. Read more »

Oct. 3 A UCLA patient carrying the CRE superbug undergoes a procedure known as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, or ERCP, with an Olympus scope; the device remains contaminated after cleaning.

Oct. 7 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports on an Illinois hospital outbreak tied to duodenoscopes that occurred despite no lapses in cleaning protocols.

Oct. 20 Aaron Young, 18, is treated with an Olympus scope at UCLA and exposed to CRE from the earlier patient.

Dec. 14 UCLA begins investigating a superbug infection in a female patient who underwent ERCP.

2015

Jan. 27 Young is treated again with an Olympus scope; his CRE infection returned.

Jan. 28 UCLA ties patient infections to the Olympus devices, halts all ERCPs.

Feb. 18 Los Angeles Times first reports the UCLA outbreak. Read more »

Feb. 19 The Food and Drug Administration warns U.S. hospitals about scopes spreading deadly bacteria. Read more »

March 4 Cedars-Sinai Medical Center reports four patients who had been infected by Olympus scopes. Read more »

March 26 Olympus issues new cleaning instructions to U.S. customers, similar to its European guidelines in 2013. Read more »

May 8 Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Torrance) criticizes the FDA's response to infections, seeks congressional hearings. Read more »

May 8 The U.S. Justice Department is investigating Olympus' role in outbreaks, the company confirms. Read more »

May 15 An FDA panel says that duodenoscopes are unsafe but that they should remain in use because no alternative is available. Read more »

June 9 Sen. Patty Murray (D-Wash.) asks Olympus for details on its response to infection reports.

Sources: Times reporting, UCLA, Olympus

Contact the reporter Chad Terhune.