In a lush enclave of an afflicted city, dozens of fledgling western bluebirds alight every spring. Kathi Rainbolt spawned the annual baby boom by setting up nest boxes in an arcade of giant pepper trees weeks after her 3-year-old grandson, Bailey, died.

The sanctuary is just one of the marks her family has left on the city since her grandfather came here to start a refrigeration business during the Depression. And Rainbolt is just one in a contingent of San Bernardino residents determined to bring back the city they once knew.

“Berdoo” was once a blue-collar, middle-class town, sustained by rail yards, an air base, a steel mill and sprawling orange groves.

Today, it’s the poorest city of its size in the state, riddled with shuttered buildings and burned-out homes. It is mired in its fourth year of bankruptcy and its third decade of a meth epidemic. Few residents can find good jobs and 91% of the city’s public school children live in poverty.

As people moved away and waves of foreclosures turned family-owned homes into cheap rentals, the fibers of community that grew over generations rapidly frayed.

But they haven’t all snapped.

Scattered across the 60-square-mile city are people who stay even as it seems there is not much to stay for. Like longtime couples who tolerate each other’s faults and still see beauty others may not, many of San Bernardino’s strongest supporters are committed for better or worse, in part because they’ve already been through so much.

They have friends, churches, clubs and surviving haunts. They like the slower pace, mountain views and historic homes under big oaks and elms. As city officials stumble forward with a bankruptcy recovery plan, these loyalists do what they can to keep the community intact.

“My parents dedicated themselves to this city,” says Rainbolt, 63. “They made this city a better place. We want our children to carry on that legacy too.”

A neighborhood changed

“There’s still nice, decent people in San Bernardino, whatever race, color or background.”

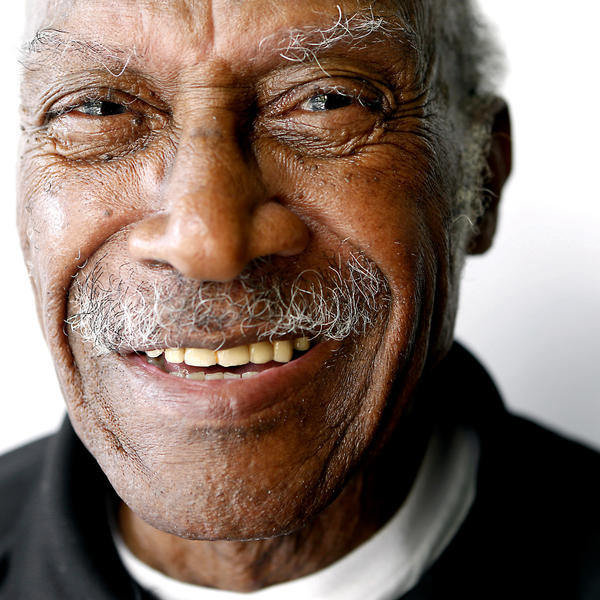

Randolph Riley, 83, made his home on the west side of San Bernardino, where most African Americans clustered. It was 1954. The decline he has seen since pains him: teenage prostitutes walking the streets, trash-filled vacant lots.

With the city in bankruptcy, the number of paid full-time code officers dropped from 27 to six. Three days a week, Riley volunteers as a code enforcement officer, pushing back against the neglect.

One morning he and his regular patrol partner, Carolyn Conley, pull up to a house that’s been charred by three fires. The city keeps boarding it up. The squatters, who set the fires, always find a way back in.

Conley, 68, peeks into the dark interior and calls out to see if anyone is there. But the occupants have left for the morning.

A neighbor, Charles Taubman, who has lived two doors down from the house for nearly 40 years, tells her about it. Pimps use it as a makeshift brothel, he says. He’s seen people drag in water heaters to strip for metal, and women leave their babies in strollers outside as they go in with envelopes and come out with small bags.

Taubman, 72, raised his boys playing football on this street. Most of the other families who owned the nearby homes are gone now, but Taubman, a former Marine, still flies the Stars and Stripes in his well-kept frontyard. He has no trouble explaining why he stays: “There’s still nice, decent people in San Bernardino, whatever race, color or background.”

“I love, absolutely love, this city, ... sometimes it looks dim and I think, ‘Oh my God, is it going to get better?’ But I know it is.”

A community in need

On a warm October night, Vicki Lee, 58, pulls up to a Days Inn on Highland Avenue with backpacks, school supplies, toothbrushes, apples, raisins and boxes of Cup Noodles. She’s helping out a single mother in crisis. The woman’s six children — the oldest is 10 — run out to Lee, hug her and dig into the supplies.

“We love you, Miss Vicki,” they say.

“Do you have any kids?” one of them asks her.

“No, I have you.”

Lee grew up on the west side of San Bernardino, like Riley, and has warm memories of her childhood. Now she works for the San Bernardino School District, making sure homeless children are in school and not being neglected or abused.

It’s more of a mission than a job. She walks the Wal-Mart parking lot late at night, looking for families sleeping in vehicles. She agonizes over the children stuck with parents on drugs. “The kids didn’t ask to come here,” she says.

One morning a week, she leaves home early to take care of her late mother’s clients at Illusion’s Beauty Salon. Working the Marcel irons and curling wax, she catches up on the lives of others who’ve stayed.

“I love, absolutely love, this city,” she says. “I know sometimes it looks dim and I think, ‘Oh my God, is it going to get better?’ But I know it is.”

A reason to stay

“Our backyard evolved over something horrible, and that's what I think is going to happen in this city.”

With the Mojave Desert to the north and the Sonoran Desert to the east, San Bernardino had an obvious need to fill when Kathi Rainbolt’s grandfather, an Englishman named William H. Bird, arrived in 1932.

The city was emerging from its cowboy era, when Wyatt Earp and his family roamed the dirt streets and cheap brothels and gambling dens drew men from as far away as Los Angeles. Bird sold refrigeration and cooling units from the clapboard garage where he kept his horses. Gradually, the machines found a niche in businesses such as the new California Hotel and the Harris Co., a department store that drew customers from all over the inland valleys and desert.

In middle school, Kathi once kissed a quick-witted prankster in the orange groves. Eventually they married.

He became a teacher at Cajon High School on the north side. They had two boys, bought a house on a street between a wash and the Arrowhead Country Club, and hung a tire swing from the avocado tree in the backyard.

One night in the late 1980s, the Rainbolts had just finished dinner when they heard pounding on the door. A moment later, four teenage skinheads kicked it in. Kathi’s husband, Bill, grabbed a baseball bat and chased them away.

They thought it was a fluke.

But in the next few years, her youngest son, Ryan, was twice held up at gunpoint. Later, just before Christmas, someone ransacked their home.

This was an era that saw the city’s economy eviscerated. Kaiser Steel, Norton Air Force Base and the Santa Fe repair shops closed, as did the Harris Co. and the California Hotel. Old friends and neighbors began moving to Redlands or the coast.

“A lot of those people, they raised their kids here,” Kathi says. “They got a lot out of this city. They took a lot out of this city. It was easier to move than it was to fight. I’m a little resentful about that.”

In 1970, 64% of residents were white. Now 16% are. The Latino population grew from 20% to 64%. It was one of a few places immigrants could afford. Median household income dropped steadily in those years, from $56,278 to $37,440 in 2013 — in inflation-adjusted dollars — transforming San Bernardino from one of the wealthier cities in the county to its poorest.

Kathi and Bill poured their time into school PTAs and youth sports, church and neighborhood associations, those basic binders of community. They maintained their church’s sanctuary garden, and their local freeway overpass. Bill did charity work through the Masonic Lodge and Scottish Rite.

But Bill had a massive stroke in 1997. He was in a coma for two months, and came to consciousness, at age 47, unable to talk or move around.

Kathi quit her job at St. Bernardine’s Hospital and became his full-time caregiver.

The doctor told her Bill needed visual stimulus to keep parts of his brain firing. She put hummingbird feeders outside so he could “catch” the birds’ fast movement through the windows.

She installed a waterfall and pond to bring more movement to that armchair view.

Her garden became her oasis.

Two years later, her eldest son’s baby, Bailey, was diagnosed with a congenital brain disorder and suffered seizures. “I would just scoop him and talk as soft as I could,” she says.

He died in 2002, before his third birthday.

In Bailey’s honor, Kathi built a “bluebird trail” of 12 nesting boxes along a lane next to a golf course.

The bluebirds came. So did neighbors, and then strangers, bringing their children and grandchildren in the spring to see the nestlings.

Bird Refrigeration closed shortly before Kathi’s father died in 2013, after 80 years in business. The recession had dealt the final blow.

Still the family pushes on. Her older son works at the Amazon distribution center in San Bernardino, and her younger son is a principal at an elementary school in one of the poorest parts of town.

City and business leaders are pushing to turn the city around by luring new industry and by transforming the school district, training students for specific high-tech design and manufacturing jobs.

Rainbolt still loves hearing the Santa Fe Depot whistle at 5 p.m., and smelling the orange blossoms on trees she planted to evoke the old groves.

The tire hanging from the avocado tree reminds her of her sons swinging or shooting BB guns through its center.

“I can’t leave this place because I still come out here and I hear two little boys laughing,” she says. “Our backyard evolved over something horrible, and that’s what I think is going to happen to this city.”

Contact the reporters Joe Mozingo and Francine Orr.

In their own words:

Betty Sutcliffe, 77

Joan Hatton

Iluminada Kellers, 83

Kathi Rainbolt, 63

Randolph Riley, 83

Carolyn Conley, 68

Michael Segura, 23

Charles Taubman, 72

Vicki Lee, 58

Tell us what you think. Leave your comments here »

Additional Credits: Digital design director: Stephanie Ferrell. Digital Producer and Developer: Sean Greene. Caption for lead photo: Michael Segura, 23, looks out from his backyard in San Bernardino. A graphic artist and leader of San Bernardino Generation Now, he and his friends are trying to get teenagers and young adults to take an active role in their city. “I feel like there’s so many opportunities here. The way I describe it to the kids, it’s blank canvas, we can create anything we want here.”