Hip-hop, not Beatles, had greatest influence on pop music, study says

Baby boomers, take a deep breath.

Hip-hop, and not the Beatles, triggered the most important evolution in American pop music over the last half-century, according to a new study by researchers in Britain.

That's based on a digital analysis of chord patterns, tonal shifts and other audio features (lyrics weren't considered) of more than 17,000 songs on the U.S. pop charts between 1960 and 2010.

The explosion of hip-hop and rap music in 1991 had far more auditory influence on the popular songs that followed than the British Invasion of 1964 or the synth-pop surge of 1983 — the other two years that saw big shifts in musical styles, according to researchers at Queen Mary University, Imperial College London and the online music service Last.fm.

The rise of Hip-hop

Thickness indicates more songs per year.

Hip-hop, rap, gangsta rap, old school

1960

1990

2010

"Hip-hop is the single greatest revolution in the U.S. pop charts by far," said Armand M. Leroi, 50, a professor of evolutionary developmental biology at Imperial College London and co-author of the study. "That surprised me. Being a victim of boomer ideology, I would have said it was 1964."

The finding challenges mainstream perceptions that the 1960s' British Invasion marked pop's most significant development of the last half-century.

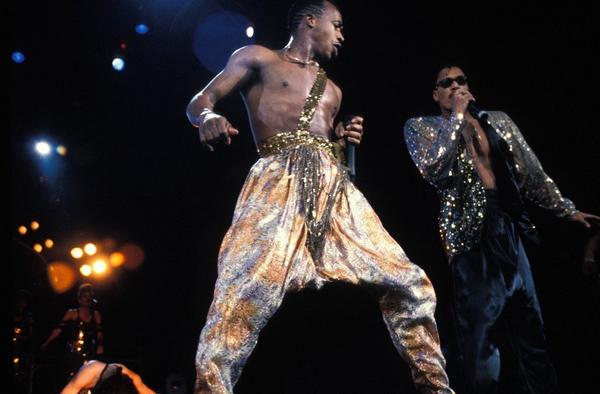

The influence of the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Who, the Kinks and other British bands of the '60s is taken as a matter of faith among the generation that came of age with those groups. By comparison, the influence of rap and hip-hop is frequently minimized in larger discussions about styles and genres that revolutionized pop music.

Born out of black urban America, rap and hip-hop are often referred to as a pop-culture game changer, but they are less frequently credited with revamping the very structure and sound of popular music as we know it.

But how do you scientifically quantify the very subjective sounds of Jimi Hendrix, the Bee Gees, Madonna, Run DMC, Guns N' Roses, Jay Z, Lady Gaga and Justin Timberlake/Bieber into cold, hard data?

Leroi and study co-authors Matthias Mauch, Robert MacCallum and Mark Levy analyzed 30-second snippets pulled from 17,094 songs, representing 86% of all the singles that charted on the Billboard Hot 100 during the 50-year scope of the study.

They tossed traditional genre classifications aside and, instead, looked at differences in chords, rhythms and tonal properties, then assigned each song to one of 13 groups based on the patterns they found.

The rise of songs without chords

Tagged as rap or hip-hop or something similar by last.fm users

Then, like evolutionary biologists who chart the differences among species in nature, they looked at diversity in pop music: When did it shift most rapidly? And what are the most critical shifts?

Among other findings, they determined that what's long been considered a seminal moment in pop music — the U.S. release of the Beatles' "I Want to Hold Your Hand" on Dec. 26, 1963 — may get too much credit for starting a revolution. Their analysis showed that musical styles were already changing before that release, suggesting that the Beatles and other British Invasion bands simply capitalized on a movement already underway.

"Evolution is a process — a process gives rise to a creature, which gives rise to [another] creature and so on," Leroi said. "The same happens when someone writes a song. They hear one and build on it."

But not everyone is sold on the use of mathematical analysis to unravel the mysteries of music.

"It's problematic that scientists are trying to assign some sort of quantitative means of assessing that importance [of pop music]," says Joanna Demers, associate professor and chair of musicology at USC's Thornton School of Music.

"Of all of the musical styles occurring in popular music around the world, hip-hop is quite important, but really it's dub reggae that's come back in everything we hear," she said, referring to a genre of electronic music that grew out of 1960s' Jamaican reggae. "I believe the software they're using wouldn't even register that."

Another key finding in the study, published this week by the journal Royal Society Open Science, has to do with what many people perceive as the declining quality of pop music.

Though music fans often lament that the deep and meaningful jams of their youth have given way to the Miley-blaspheme of today, the team's data suggest that they're letting emotion cloud the real story.

Despite the advent of Britney, Imagine Dragons and Flo Rida, empirical evidence suggests that music is no more shallow or vapid than it once was.

The study found that diversity in pop music has persisted and flourished over time — except for a stretch around 1986 when synthesizers and drum machines invaded our better senses and "everything sounded like Duran Duran," Leroi said.

Critics argue that many of the revelations in the study, in fact, echo what we already know about the trajectory of pop through anecdotal evidence. There's plenty of wiggle room in the British study given that it does not take lyrical content, social factors, cultural markers or the wonderfully bizarre performance qualities of artists into account.

Or put another way, can music really be understood through a lab project?

The British researchers say, yes, and that "musical lore and aesthetic judgments" pale next to "rigorous tests of clear hypothesis based on quantitative data and statistics."

"You can say, ‘This is really when it happened,' " Leroi said. "It's not just, ‘Things were really cool at CBGB's or on the Sunset Strip back then.'"

USC's Demers disagrees, pointing out that researchers in the humanities would be laughed at if they were to insist on bringing a nonscientific viewpoint to a subject such as evolution.

"It's an unnecessarily contentious thing to say, that humanists don't have anything important to say because we don't deal with mathematically acquired data," she said. "Imagine [if we] wrote a paper about evolutionary theories that said, ‘Scientists don't give us what we really want, which is more touchy-feely stuff.' "

How what you eat demands more water than you think it does

How what you eat demands more water than you think it does Run the L.A. Marathon without ever breaking a sweat

Run the L.A. Marathon without ever breaking a sweat California's worsening drought

California's worsening drought 6 Girl Scout Cookies you thought you were getting but aren't

6 Girl Scout Cookies you thought you were getting but aren't