By his own account, Patrick J. O’Reilly was at times “a cheerleader and an advocate” for the Missile Defense Agency during his four years as director. But he broke ranks with his predecessors at the agency by questioning flawed programs that cost taxpayers billions of dollars.

In a series of interviews, O’Reilly said members of Congress whose states or districts benefited from missile defense spending fought doggedly to protect three of the programs long after their shortcomings became obvious.

He described how Rep. Howard “Buck” McKeon (R-Santa Clarita) reacted when he outlined his reservations about the Airborne Laser project, envisioned as a fleet of Boeing 747s that would be modified to fire laser beams at enemy missiles.

O’Reilly, who led the agency from 2008 to 2012, said he told McKeon in private Capitol Hill briefings that the planes would have to fly so close to their targets that they would be defenseless against antiaircraft fire.

“Buck McKeon just ripped me apart,” said O’Reilly, a physicist and retired Army lieutenant general. “He’d immediately start talking about, ‘OK, we’ve got a problem. So how much money are you putting towards the problem? How much money do you need?’ I was trying to say, ‘On the technical merits, it doesn’t make sense.’”

McKeon served four years as chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, and his district adjoined Edwards Air Force Base, where Boeing Co. and other contractors were developing the Airborne Laser. The project was killed in 2012, after a decade of testing and $5.3 billion in spending.

McKeon, who retired in January, did not respond to messages seeking comment.

O’Reilly grew skeptical of another missile defense project, the Kinetic Energy Interceptor, after he learned that Navy ships would have to be retrofitted — at a cost of billions of dollars — to accommodate the 40-foot-long rocket. Existing ships could not carry interceptors longer than 22 feet, he said.

Expensive duds:

Airborne Laser

Kinetic Energy Interceptor

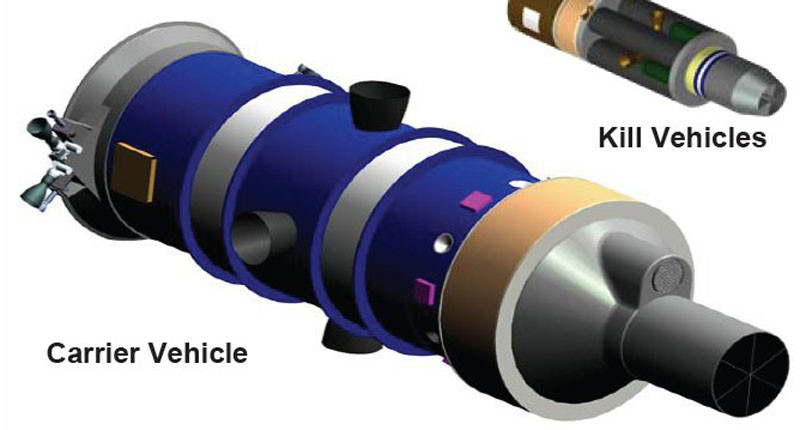

Multiple Kill Vehicle

Sources, top to bottom: U.S. Department of Defense | Northrop Grumman Corp. | GlobalSecurity.org

“This was unbelievably expensive — to mess with the fundamental structure of a ship,” he said. "The technical issues were not minor; they were revolutionary.”

The project’s backers included Sen. Jon Kyl of Arizona, then the second-ranking Republican in the Senate, and GOP Sens. Jeff Sessions and Richard C. Shelby of Alabama. O’Reilly said the three senators bristled when he suggested that the Kinetic Energy Interceptor was unworkable.

Many of the jobs related to the program were in Alabama and Arizona.

“When I would say things like, ‘I’m having difficulty understanding, sir, how to put this on a ship,’ the answer would come back, ‘We have very smart aerospace engineers and we have the strongest military-industrial complex in the world. We can solve anything,’” O’Reilly said. “And they would hand-wave.”

Shelby, in a May 13, 2009, letter to O’Reilly, said killing the Kinetic Energy Interceptor would be "irresponsible.”

The program nevertheless was discontinued that year. By then, $1.7 billion had been spent on it.

O’Reilly said the same three senators defended another project, the Multiple Kill Vehicle, after he raised questions about its feasibility. The project envisioned a cluster of tiny interceptors that would destroy enemy missiles in space. It was shelved in 2009, after nearly $700 million had been spent.

Neither Shelby nor Sessions responded to emails and phone messages seeking comment.

Kyl, now a Washington lobbyist, said that he did not recall discussing specific defense systems with O’Reilly, and that he supported “the most funding that we could possibly get” for missile defense, regardless of the economic benefit to Arizona.

“I believe that having a robust missile defense to protect the United States is a critical component of not only national defense but our strategic deterrent,” Kyl said. “I’m not pleased that after all this time and a great deal of money spent, we don’t have more to show for it than we do.”

O’Reilly, now 58 and living near Huntsville, Ala., said he regretted that elected officials did not focus on the cost and practicality of the troubled projects.

“These things really didn’t have a lot of merit,” he said. “It was just how they were packaged and sold in Washington.”

Read more: Failed missile defense programs cost U.S. nearly $10 billion »

Additional Credits: Digital Design and Development: Lily Mihalik and Evan Wagstaff. Lead image: SBX passes the Seattle skyline just before arriving at Vigor Shipyards. (Boeing / Missile Defense Agency)