Walking in L.A.: Times analysis finds the county's 817 most dangerous intersections

It's evening rush hour near MacArthur Park, and the streets teem with activity.

Crowds pack the crosswalks, weaving around cars that nose through to make right turns. Men pull food carts and women push strollers toward the Metro Rail station, accompanied by the strains of pop music from cars and businesses.

This is the kind of dense, transit-oriented neighborhood that Los Angeles officials say the car-clogged city needs to replicate.

But Westlake's bustling character also makes it one of the city's most dangerous areas for pedestrians: On four blocks of South Alvarado Street, the neighborhood's backbone, 90 people were hit by cars in a period of 12 years.

A Los Angeles Times analysis shows nearly a quarter of traffic accidents involving a pedestrian occur at less than 1% of the city's intersections. Many of the most dangerous crossings, which see a disproportionately high rate of crashes, are clustered in high-density areas between downtown Los Angeles and Hollywood.

Pedestrians were involved in 1 in 10 traffic accidents in Los Angeles from 2002 through 2013, but represented more than 35% of road deaths. Many of the fatalities occurred on long, straight streets or near freeways.

Urban planners say the data highlight the great challenge in Los Angeles' quest to be more pedestrian friendly: Its wide boulevards and sprawling grids, designed to move cars as quickly as possible, are vestiges of the past that put pedestrians of the present in danger.

Have you been involved in a pedestrian-related accident?

Share your story »Over the last five years, Los Angeles has sought to tame the traffic. Officials have added more than 200 miles of bike lanes, installed high-visibility crosswalks and pushed for more mass transit, hoping to breathe life back into commercial boulevards and coax Angelenos out of their cars.

But the work is far from done.

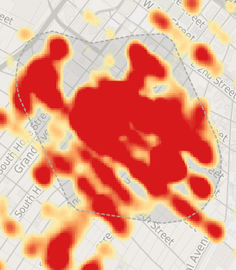

Concentrations of pedestrian accidents and problematic intersections

From 2002 through 2013, more than 58,000 accidents involving pedestrians occurred in L.A. County. A Times analysis identified more than 800 highly problematic intersections, which had a higher rate of pedestrian injury or death than county averages. Many intersections were clustered in dense neighborhoods such as downtown L.A., Koreatown, Westlake and Hollywood.

Please rotate your device

For the Record

July 14, 2015: Due to a geocoding error, an earlier version of the interactive map accompanying this article incorrectly located three intersections. After relocating these intersections and recounting collisions, Western Avenue and 48th Street was removed from the map; Western and 29th Street was added. Western's intersections with 36th Street and 38th Street were moved from Torrance to the correct locations in West Adams. The changes had a slight effect on the display of the heat map.

“Safety should be our north star,” said Seleta Reynolds, the Los Angeles Transportation Department's general manager. “So many people are being injured and killed. It's an invisible impact on families and on our city.”

Using data collected from reports that law enforcement agencies send to the California Highway Patrol, The Times analyzed more than 665,000 traffic accidents in L.A. County from 2002 through 2013 and identified 579 intersections in Los Angeles where the reported rate of crashes between cars and pedestrians was significantly higher than the county average.

Downtown L.A.

The largest number of problematic intersections for pedestrians are in Downtown L.A. a Times analysis shows. The area has 48 dangerous intersections, almost as many as Koreatown and Westlake combined.

Many of the city's intersections have never seen a pedestrian accident. But among those that have, a tiny fraction of crossings has recorded an outsized number of crashes.

Resurgent downtown Los Angeles has the highest concentration of those intersections, The Times found. More than 600 people on foot were hit by cars at 48 intersections over those 12 years, or an average of one person per week. Eleven people were killed.

In Westlake, near MacArthur Park, 343 pedestrians were struck and three were killed in an area of less than one square mile.

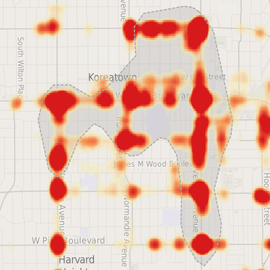

In Koreatown, near the nexus of two Metro rail lines, more than 400 people on foot were hit by cars over the same period, 11 of them fatally.

“There's this perception — not just in Los Angeles, but in other major cities — that nobody walks,” said Janette Sadik-Khan, a former New York City transportation commissioner who is now a principal at Bloomberg Associates, which advises cities on quality-of-life issues. “That's not only an inaccurate, but a deadly perception.”

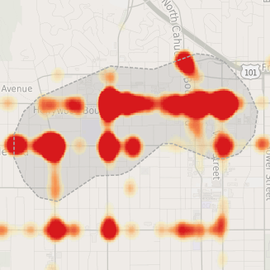

The data also showed that some of Hollywood's iconic boulevards — Hollywood, Sunset, Santa Monica — are perilous for pedestrians: 369 people were hit by cars at 23 intersections that The Times identified as dangerous. Eight people died.

At Hollywood Boulevard and Highland Avenue, just outside the TCL Chinese Theater, 38 pedestrians were hit by cars, and one was killed. Traffic is notoriously slow there, and experts say newer crosswalks and traffic signals help keep pedestrian incidents from happening even more frequently. But the throngs of people on foot, many of them tourists, who crowd the sidewalks make safety improvements paramount.

“The streets should be designed for people who are completely unfamiliar with them,” Ryan Snyder, a transportation planner and UCLA professor, said as he watched traffic at the busy intersection.

Moments later, a woman stepped off the curb next to Ripley's Believe It or Not and snapped a selfie in the crosswalk, a Hollywood Boulevard street sign behind her.

In this area of Hollywood, Snyder said, adding so-called curb extensions would improve safety. Bumping the corners of the sidewalk farther out into the street could eliminate a lane of traffic — an unpopular proposition among harried L.A. drivers — but would reduce pedestrians' crossing distance. Using what was formerly the right-hand travel lane, he said, officials could add bicycle lanes, bigger bus stops or more street parking.

One consolation for drivers: Restriping the street can sometimes lead to more efficient traffic movement. “Two good traffic lanes work better than three bad ones,” particularly when cities add turn lanes and improve intersection design to reduce crashes, Sadik-Khan said.

Only one intersection in Los Angeles County saw more pedestrian crashes than Hollywood and Highland. At Slauson and Western avenues in South Los Angeles, 41 people were hit by cars over the 12-year period.

“There is so much work to be done here,” Deborah Murphy, an urban planner who runs Los Angeles Walks, a pedestrian advocacy group, said as she surveyed the streets on a recent afternoon. The wide intersection, anchored by three strip malls and a gas station, felt like a highway: Cars sped through it, and vehicles leaving parking lots narrowly zipped past children on bikes and old women with wire carts.

Hollywood

Covering roughly the area bordered by Hollywood Blvd., Sunset Blvd., Vine St., and Highland Ave., 23 Hollywood intersections saw 369 people hit by cars, including eight deaths.

Away from L.A.'s congested core, wide streets like these can invite speeding or rapid lane changes. Adding taller buildings or trees that arch into the roadway could narrow drivers' field of view, Murphy said, adding more shade for pedestrians and subconsciously signaling drivers to slow down.

Another factor that makes Slauson and Western so dangerous, Murphy said, is that pedestrians must cross five lanes of traffic, or about 70 feet, to reach the opposite corner.

“That's a long way for an able-bodied person,” Murphy said. “Now think about people who do it in a wheelchair.”

At each corner of the intersection, one ramp points people with wheelchairs or strollers into the middle of the intersection. The better, but more expensive option, Murphy said, would be to add one ramp at each crosswalk. The city also could install sharper curbs that force drivers to brake as they turn, she said.

Only about 3% of the pedestrian accidents from 2002 through 2013 were fatal, according to the analysis. But even less-severe crashes can take a major toll.

On a warm summer afternoon four years ago, Azurell Papka, then a 32-year-old IT specialist who walked and took the bus to work, stepped out of her office in North Hollywood as the sunlight began to fade.

The walk signal flashed at Magnolia Boulevard, and she began to cross. A Toyota Corolla made a right turn into the crosswalk and knocked Papka's legs out from under her, throwing her to the ground and tearing her rotator cuff. After several surgeries to repair her shoulder and wrist, Papka sued the Corolla driver and settled out of court.

With the money she paid her hospital bills — then bought a car.

“I still get nervous there,” Papka said of the intersection. “There's been at least one death on that corner. I'm just thankful it wasn't me.”

After decades of urging the city to improve pedestrian infrastructure, advocates say they are finally seeing incremental changes.

Mayor Eric Garcetti's office said officials will introduce in August a plan aimed at eliminating all traffic deaths by 2025, a “Vision Zero” policy that mirrors initiatives in New York, San Francisco and several European cities.

Downtown, some traffic signals have been re-timed to give pedestrians a head start, and a lane of traffic on Broadway has been replaced with umbrellas and outdoor seating to encourage walking and slower driving.

Analysts used five years of data to create “crash profiles” of city corridors. That will help officials decide how to spend their limited budget where it counts, the Transportation Department's Reynolds said, to alleviate the “public health crisis” of traffic deaths.

Knowing that most crashes at a certain crosswalk involve right-hand turns, for example, could prompt a re-timed pedestrian countdown signal, giving walkers a several-second head start before cars can turn into the crosswalk — a relatively easy and cheap way to make people on foot more visible to drivers. Other intersections may benefit from speed feedback signs or high-visibility crosswalks.

But where intersection transformations will happen in Los Angeles, and how that work could be funded, remain unclear.

Installing high-visibility crosswalks, with wide stripes and bright paint, costs an average of $2,500 in Los Angeles. Overhauling a street to add broader curbs, ramps or a median costs far more, particularly if the street must be reshaped to accommodate storm drains or higher curbs. In Pasadena and Long Beach, curb extensions cost between $20,000 and $120,000 per corner.

Koreatown

Koreatown doesn't just have a large number of pedestrian accidents, it has a large number of all types of crashes. More than 400 people on foot were hit at 29 Koreatown intersections, 11 of them fatal.

The city could also look to San Francisco for inspiration. Officials there recently moved to ban turns onto a mile-long stretch of Market Street to reduce conflict points between drivers, walkers and cyclists.

In the San Fernando Valley, which has a reputation for street racing, police are stopping drivers and warning them about speeding. “The stop is just as valuable as the cite,” Los Angeles Police Department Capt. John McMahon told commanders at a recent meeting.

In tandem with education and enforcement, reducing speed limits also can significantly reduce severe injuries and deaths, particularly near crosswalks without traffic lights, said Brian Tefft, a senior research associate at the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety.

Last fall, New York officials reduced the speed limit from 30 mph to 25 mph on 90% of city streets. The change sounds marginal, Tefft said, but it's designed to help pedestrians survive a crash.

At greater speeds, pedestrians are more likely to hit the windshield or be thrown through the air. Bones and organs can't withstand the impact of steel and glass. Pedestrians face a 25% chance of severe injury if they are hit by a car driving 23 mph, Tefft said. The risk rises to 75% if the car is going just 16 mph faster.

One more hurdle is the court of public opinion. Drivers often bristle at the idea of losing lanes of traffic. But, advocates say, weighing safety against traffic flow is a false equivalence.

“The common way to think about this is, we don't want to do anything that compromises car movement,” UCLA's Snyder said. “But is it more important to save yourself 10 seconds as you drive, or to save lives?”

Times staff writers Ryan Menezes and Doug Smith contributed to this report.