Eight men tell stories of innocence and fights for compensation

By Molly Hennessy-Fiske

They are among the hundreds of people who have been imprisoned for crimes they did not commit — robbery, rape, kidnapping and murder. First they had to prove their innocence. Then they fought to be compensated for their time behind bars. Eight men share their stories

Robert Dewey

- Age: 54

- Colorado

- Wrongful conviction: Rape and murder

- Sentence: Life

- Served: 16 years

He resembled an extra from “Sons of Anarchy.” Known to fellow bikers as “Rider,” Robert Dewey sported a long goatee, braid and beefy forearms laced with tattoos.

But he was no murderer.

Exonerated by DNA two years ago, he urged Colorado lawmakers to pass exoneree compensation legislation. When the governor signed the bill into law last year, Dewey rented a car and drove 244 miles from the mountains of Grand Junction down to Denver to watch. Then he drove back — he couldn’t afford to stay.

His compensation started in fall 2013: $100,000, the first annual payment out of $1.2 million.

Like lottery winners, many exonerees have little experience managing such huge sums. Under the new law, Dewey was supposed to take a budgeting class, but he delayed. By winter, he had burned through most of his first check.

He spent it on his parents and seven grandchildren, on a 1998 Ford truck, a $23,000 custom motorcycle, a friend’s pit bull puppy named Spartacus and a half dozen diamond stud earrings. He repaid friends who had loaned him money and provided loans to others.

Last December, disaster struck.

Dewey was hospitalized. Surgeons attempted to mend throat damage related to a prison work injury. Complications required a second surgery, and he was discharged in a wheelchair. His relationship with his girlfriend frayed and she kicked him out of her apartment.

“I just don’t know how much more I can take,” he sobbed.

Dewey pawned his diamond earrings. He piled most of his belongings in his truck and hauled them to a storage unit, rented a one-bedroom basement apartment surrounded by salvage yards and stocked it with cheap food — jelly sandwiches and off-brand Lucky Charms. In the summer, he had more surgery to repair his back and hung on until his next check arrived in the fall.

Then things started looking up.

He met a widow at a garage sale, moved in and married her Nov. 20. He bought new diamond earrings, a pit bull puppy named Girl, a $7,500 motor home, $3,000 trailer and a couple Harley-Davidson motorcycles they plan to take to Phoenix. This month, a filmmaker documenting his exoneration planned to fly the couple to Los Angeles for filming, and Dewey expected to visit his mother in Ridgecrest for the first time since his release.

“Finally, something good is happening for me,” he said.

Photo by Ed Andrieski/Associated Press

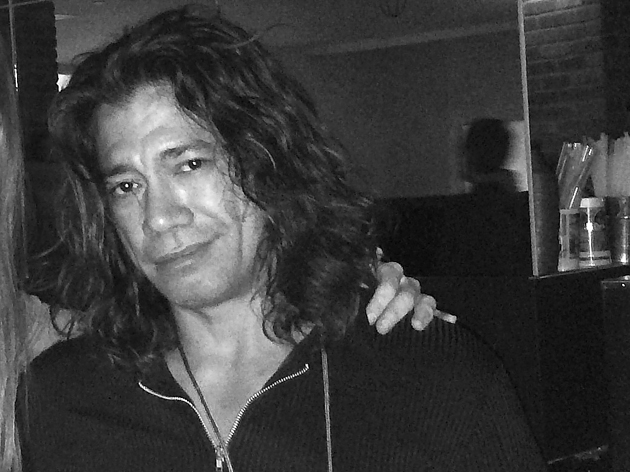

Jose Diaz

- Age: 50

- San Jose

- Wrongful conviction: Rape, attempted rape, oral copulation, penetration with a foreign object

- Sentence: 15 years

- Served: 9 years

Jose Diaz was paroled and forced to register as a sex offender for years before he found an attorney — his fourth — who was able to persuade prosecutors that the attacks were linked to a serial criminal known as the Hooded Rapist. His convictions were vacated, charges were dismissed in 2012 and a judge found him factually innocent.

But when he sought compensation, state attorneys argued that Diaz had waited too long to apply — even though he applied shortly after he was cleared.

“They’re trying to base it on a technicality instead of justice,” said Diaz, a tech worker and married father of four who lives paycheck to paycheck.

He had been cleared with help from local prosecutors, including the head of the Santa Clara County district attorney’s conviction integrity unit.

“We view an exoneree as someone who was a victim of a crime,” Assistant Dist. Atty. David Angel said, adding that in Diaz’s case, “We do not believe he committed the crime, technically and actually. We believe he served a sentence he should not have.”

“The district attorney should be the ultimate authority on whether a conviction was valid or not,” Angel added — not the state compensation board.

Diaz hired a lawyer, but it still took him two years to appeal and get a Superior Court judge to order the state compensation board to approve his $305,300 payment this year, which he didn’t receive until November.

“They’re spending more money fighting these cases,” he said. “It’s unethical.”

Anthony Graves

- Age: 49

- Texas

- Wrongful conviction: Capital murder

- Sentence: Death

- Served: 18 years

Anthony Graves spent a dozen years on death row, where he was scheduled for execution twice.

He was convicted in 1994 of killing a 45-year-old woman, her 16-year-old daughter and four grandchildren in a single stoplight town about 90 miles northwest of Houston. The victims were variously beaten, stabbed, strangled and shot.

The sole witness to the crime was also charged and initially implicated Graves, but later recanted. Graves’ conviction was overturned and he was released in 2010.

Because prosecutors fought his exoneration, Graves was not initially compensated. It took a year of lobbying for legislators to pass a special bill granting him compensation under state law, about $1.5 million.

“They go to great lengths to make sure you don’t receive the money,” he said of prosecutors. “I just had the public on my side.”

Graves filed a complaint with the state bar against his prosecutor, former Burleson County Dist. Atty. Charles Sebesta. In March, the bar announced plans to investigate. In July, the bar found just cause for the complaint to go to court, and the prosecutor elected to have it heard by an administrative judge, sealing the proceedings.

Sebesta maintains that he committed no misconduct in the case, and that Graves is guilty.

Graves said he pursued the complaint because he wants to prevent prosecutorial misconduct and send a message to the public that it won’t be tolerated.

“What you’re doing is trying to restore faith in the criminal justice system,” he said.

Photo by Marie D. De Jesus/Associated Press

Alvin Jardine

- Age: 45

- Hawaii

- Wrongful conviction: First-degree sexual assault, attempted sexual assault, first-degree terroristic threatening, kidnapping, burglary

- Sentence: 35 years

- Served: 19 years

Alvin Jardine had spent more than a decade in prison when his younger sister urged him to say he was guilty. If he admitted guilt and showed remorse, she said, the Hawaiian parole board might free him.

“She told me, ‘Just look at it as a means to an end,’” recalled Jardine, a native Hawaiian with a surfer’s tousled, shoulder-length hair, muscled shoulders and lilting voice.

But he refused to lie.

“If I have to do 35 years, I’ve got to do 35 years,” he told her. “I’m not going to admit to something I didn’t do.”

At the time of his arrest, Jardine had been an apprentice carpenter earning $16 an hour building million-dollar homes. His daughter was nearly 3 years old. He was getting married to her mom, had just bought a truck and some tools.

Jardine was freed three years ago but still feels like he’s been spit from a time machine, a 21-year-old trapped in a middle-aged body. In prison, he grew accustomed to guards telling him when to come and go. Without them, he feels aimless. He has trouble dealing with people back in Maui.

“If someone raises their voice to me, I get issues. Because in prison, that’s what it’s about — respect,” he said.

That makes it hard to find steady work.

“It’s not that I cannot find one job — it’s that I cannot keep one job,” Jardine said. “I get attitude if somebody speaks to me the wrong way. I don’t know really what’s tactful, what’s required outside.”

Jardine lives on the beach, showers at his girlfriend’s house and borrows her truck to get groceries he can barely afford. “I’ve got to go hat in hand and beg for food stamps,” he said. “Freedom comes with a price.”

This year, Hawaiian lawmakers rejected legislation to compensate exonerees.

Photo by Molly Hennessy-Fiske/Los Angeles Times

Alan Northrop

- Age: 50

- Washington State

- Wrongful conviction: Rape, robbery, kidnapping

- Sentence: 23 years

- Served: 17 years

Three years after Alan Northrop and his codefendant were freed by DNA testing, they were lobbying state legislators to pass a compensation law.

“It’s tough,” Northrop testified last year, his voice breaking, “I really hope this bill passes, not just for us — there’s other gentlemen in prison locked up wrongfully right now.”

Northrop looked like the clean-cut father of three he had been before he was wrongfully convicted. Back then, he was logging and starting an excavating business in his rural hometown of Woodland. The conviction smeared him and his family.

He told lawmakers he still owed $111,000 in back child support accrued while he was in prison. When he was released, he was homeless, forced to stay at his brother’s. Supporters gave him a used pickup truck, and he found a factory job that paid $11 an hour. But he still could not afford health insurance. He knew another exoneree who couldn’t find work to support his family, then was hospitalized with pancreatitis.

As Washington lawmakers debated the proposed compensation law, Rep. Brad Klippert, a Republican, was skeptical.

“For someone to be found guilty of a crime, especially of a felony crime, they have to have been found guilty by beyond a reasonable doubt by either a jury of their peers or by a judge,” he said at the hearing.

It was the third year Northrop had testified for compensation legislation. But this time, it passed.

Among other things, it entitles exonerees to $50,000 for each year in prison and awaiting trial, an added $50,000 for each year on death row and $25,000 for each year spent on parole, community custody or as a registered sex offender.

Northrop went to Olympia to watch the governor sign the bill into law. Afterward, a lawmaker stopped to shake his hand. It was Klippert, who had spoken out against the law but changed his mind and voted for it. Now Northrop heard him say, “Congratulations to you.”

Photo by Molly Hennessy-Fiske/Los Angeles Times

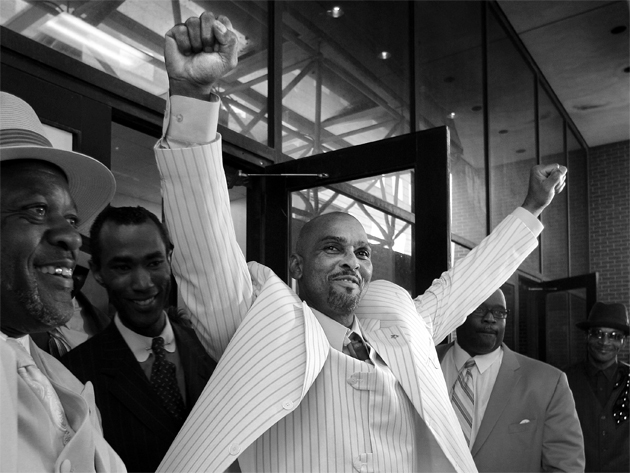

Johnny Pinchback

- Age: 58

- Texas

- Wrongful conviction: Aggravated sexual assault

- Sentence: life

- Served: 26 years

Johnny Pinchback won his freedom thanks to help from another Dallas exoneree he met in prison.

Charles Chatman, 54, had also been wrongfully convicted of rape. He served 27 years before DNA testing proved his innocence in 2008.

After his release, Chatman pushed Innocence Project lawyers and the Dallas district attorney to help Pinchback, who had been convicted in 1984 of raping two teenage girls at gunpoint.

In 2010, DNA tests of the rape kit in his case implicated another man. The following year, prosecutors dismissed the charges, and he was released.

Both Pinchback and Chatman received compensation payments from the state, more than $2.1 million each, plus a monthly annuity of about $12,000.

They still live in the Dallas area, where they attend services together at Greater Peoples Missionary Baptist Church.

Pinchback is long, lean and stylish, sporting sleek suits on Sundays to sing in the men’s choir. Chatman, a strapping but reserved figure with a shiny shaved head, usually slips in quietly beside Pinchback’s family.

During a service last year, Chatman and the rest clapped as Pinchback sang, “The angels keep watching over me.”

When the pastor urged Pinchback to offer the congregation some words of encouragement, he stepped to the altar.

“Keep trusting in the Lord,” he said, and smiled at Chatman.

Photo by Tony Gutierrez/Associated Press

Mario Rocha

- Age: 35

- Los Angeles

- Wrongful conviction: Murder and attempted murder

- Sentence: 29 years to life

- Served: 10 years

Mario Rocha’s struggle to overturn his wrongful conviction attracted a slew of supporters, including an activist nun, pro bono attorneys and filmmakers who made the documentary “Mario’s Story.”

But when he applied for state compensation, few expected him to succeed and he was left to fight alone, acting as his own attorney.

Rocha was released in 2006 after an appeals court judge overturned his attempted murder conviction for a 1996 Highland Park gang shooting, citing ineffective assistance of counsel. Los Angeles County Deputy Dist. Atty. Robert “Bobby” Grace said he did not pursue a retrial because too much time had passed to mount an effective case.

When Rocha applied for compensation, the California attorney general’s office insisted he was guilty and contributed to his conviction by associating with a gang.

Rocha rejected that claim when he testified last year before a state compensation board officer.

“I grew up in prison. I wasn’t from a gang, but I do know people from every gang in California,” Rocha said.

By then, lawmakers had removed the provision in the law barring compensation to those who contributed to their convictions.

The attorney general’s office switched its position to support Rocha’s claim, noting that he may have belonged to a gang but “probably did not commit murder or attempted murder.”

The hearing officer recommended the state compensate Rocha, and on Dec. 12 of last year, the compensation board voted 2-1 to grant Rocha $305,900. The dissenting vote came from San Bernardino County Dist. Atty. Michael Ramos, who still questioned Rocha’s innocence.

Afterward, Rocha emailed supporters to criticize the “unpredictable state” for being “hell-bent on defending its crimes rather than holding itself accountable like a republic that is righteous in practice, not just rhetoric.”

Rocha had to wait more than six months for his compensation to be approved by the Legislature in June. Months later, he had still not received compensation.”I am ashamed and alarmed as I explain to my skeptical, struggling mother, ‘The money is coming, Ama, I know it seems unreal. But I have no control over this process once again,’” Rocha said.

He received his check last month.

Photo by Mel Melcon/Los Angeles Times

Johnny Williams Jr.

- Age: 39

- Hemet, Calif.

- Wrongful conviction: Lewd conduct against a child under age 14 and attempted rape

- Sentence: 16 years

- Served: 13 years

Last year, a judge declared Williams factually innocent — two months after he had been released on parole and forced to register as a sex offender.

In 2000, Williams had been convicted of molesting a 9-year-old girl in Oakland. He was exonerated after DNA recovered from the girl’s shirt pointed to the real molester.

Once he was cleared, his name was removed from the sex offender registry and word spread that he was eligible for compensation.

“Everybody wanted me to stay with them,” Williams said.

Williams stayed first with a sister in Texas, then with another in Hemet. He applied for compensation, but it took months for state officials to consider his claim.

He soon wore out his welcome with his relatives. Unemployed, he took shelter in the spare room of a church.

“I left the streets and now I’m back on the streets,” he said.

He had trouble finding work. The oldest of four children raised by a single mother, Williams had dropped out of school in seventh grade. He got licensed as a forklift operator and hoped to get hired at an Inland Empire warehouse. With donations from supporters, he bought a black 1997 Saturn to drive to job interviews.

“I have to work. I can’t just sit back and hope this comes through,” he said of compensation. “I need money right now.”

In May, still unable to find a job, he brought his compensation claim before the state board. They unanimously voted to pay him $461,600.

He bought a new SUV, a 2013 Dodge Journey, and this month closed on a two-bedroom house in Hemet.

Williams gave most of his compensation to a financial advisor at his bank.

“What I learned: It’s not enough money,” he said during a recent visit with his pastor. “That’s why I invested it, and I bought the house and put a lot of the money up. I’m going to get a job and stay in touch with people from the church.”

Photo by Brian van der Brug/Los Angeles Times

Read the story and watch the full video at latimes.com/exonerees

Credits: Production by Jerome Campbell