She ran across the rocks, turning to face the spot where, 40 years into her past, Julie Lam stepped off a bus and into a new life.

“This is really it?” Lam whispered to herself. “This is it. I am here — where we all started.”

Standing in the shadow of the mountains, the 54-year-old blinked away tears, remembering the old bus winding its way through rows of barracks, suddenly stopping, its ragtag passengers turning wide eyes toward a door that swung open.

A deep voice speaking “American” announced: “Welcome to our base. Let’s look at where you’ll be staying. We hope you will feel safe.”

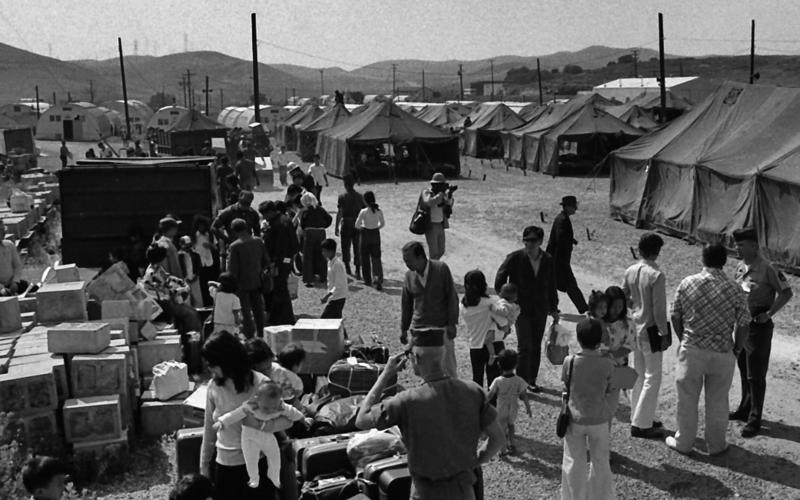

Some of the men, women and children peeked at the stranger, not understanding. With his hands, the Marine beckoned them, guiding the elderly down the steps to the sandy ground of Camp Pendleton.

As Lam and the others emerged in the cold air, another jolt greeted them — in the arm. A nurse stood poking them with inoculations. At the next station, they walked away with “health and comfort” packets stuffed with a washcloth, toothpaste, tiny bottles of shampoo. A cluster of Marines handed the shivering newcomers what many would wear morning to night: standard-issue military jackets that stretched to a youngster’s knees — one size fits all.

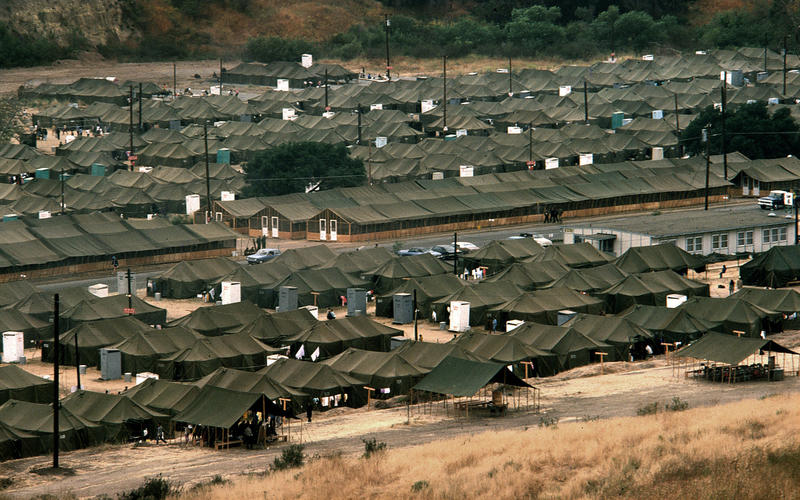

It was late April 1975. Saigon was teetering. Almost overnight, refugee camps had sprung up across the U.S. to shelter an exodus of 100,000-plus Vietnamese.

With just 36 hours’ notice, enlisted crews rushed around Camp Pendleton, sweeping the grounds, laying plywood floors, setting up hundreds of tents and thousands of cots, stocking pantries.

Inside the tent city, the lost and the bewildered roamed, one of them describing their arrival “like coming to the promised land — just that we didn’t know what was promised or where we would land.”

For Lam and fellow evacuee Lisa Ha Nishihara, fear and confusion became their companions, girls on the brink of an undefined future.

By April 30, Saigon had fallen. The Vietnam War was over. The refugees listened to the news on the radio, their tears streaming long past dawn.

They had lost not just a war, but a country.

The night before the trip that would change their lives, the Lam siblings lounged in their parents’ bedroom in Saigon, in a two-story villa across the street from the home of South Vietnam’s vice president. An uneasy silence replaced their usual banter.

Finally, their father spoke. “I need to tell you what will happen tomorrow. We’re going to America. We have a chance to escape. But it will be like night and day,” Tuan Lam warned. “To survive, we’ll have to find jobs. We’ll have to work very, very hard. But I don’t mind — as long as we stay together.”

Tuan Lam’s parents started to fret. His children still did not talk. In the homeland, their dad never feared providing for them, owning a host of factories and supplying uniforms, food and building materials to the U.S. Army and Navy. Yet at 45, he would be starting over.

Julie, his middle child, a 14-year-old with serious eyes, went to her room, fetching an allotted two items of clothing for their journey. Her pregnant mother worried for her and her older sister.

“She told me: ‘If there’s something harmful, the boys can take care of themselves. But what would the girls do?’” Lam recalled.

On April 21, as nervous South Vietnamese soldiers patrolled Saigon, the Lams left their haven and boarded a flight to Manila, a refueling stop, then on to Los Angeles, where they transferred to a Greyhound bus for the trip to Camp Pendleton.

“The roads leading us to the base were huge — I mean huge. I wondered, what must this place be like? We were all scared and just followed directions,” Lam said.

Inside Pendleton, it didn’t matter where folks came from, what they might have carried, even that the Lam daughters had arrived with $20,000 sewn into pouches inside their pants — in case of emergency. Everyone struggled with resettlement. Camp life was the great equalizer.

Because the Lams were among the first families to enter camp, pale-skinned Marines escorted them to a Quonset hut.

“We couldn’t believe it. It had real doors — none of the tent stuff — those tents were freezing,” Lam remembered. She lay near her sister, as they both helped their mother, who had given birth to a sixth child upon leaving their homeland, a boy named Tien.

Lam took turns washing his cloth diapers. One afternoon, the family received an unheard-of-gift. “They gave us U.S. diapers. Disposable diapers! We didn’t even know they existed,” Lam said.

Food was also an unknown territory. At the mess hall, servers plunked blobs of corned-beef hash onto her plate. Hamburgers and hot dogs had a squishy texture.

“The portions were American-men-type of huge,” she said. “We couldn’t get that much in.”

The best part were the nights, when they would gather to watch movies shown on a giant screen, wishing they could figure out the foreign words. Under the starry skies, the refugee kids looked like tiny adults, pulling their military jackets close.

Her father stayed busy, shaking hands, introducing himself, frantic to find off-base housing — and a new profession.

Luckily, Tuan Lam had brought a prized possession: his resume. It was nestled with letters he had received from Army Gen. William Westmoreland, commander of U.S. military operations for a time during the Vietnam War, and former Vice President Hubert Humphrey. Both men had toured his businesses.

“My father kept telling us to stay calm. I kept thinking: This is temporary, even though we were told it would be forever. In my mind, we’re going back. We’re going back — some day.”

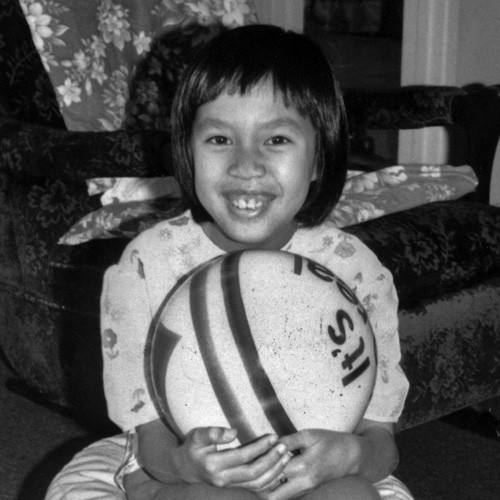

There she was, the girl with the startled elfin face, peeking from a 4-decade-old photograph with her great-grandmother.

She touched the black-and-white image, tracing the outline of her elder’s wrinkles, her cheeks wet from crying. “I remember her, but I do not remember enough,” said Lisa Ha Nishihara, then a 5-year-old called Ha Hoang.

What comes to her mind is her small self, weaving between the cots at Camp Pendleton, her feet clinging to flip-flops that were her only shoes. Little Ha Hoang followed the woman, Tran Thi Nam, everywhere.

At 109, the oldest resident at Pendleton had survived both Chinese and French invasions of Vietnam. She raised six children, who gave birth to her grandchildren, who bore her great-grandchildren. They spent each day among four generations on the island of Phu Quoc, fringed with white sandy beaches and dotted with dense, tropical jungle. She and her husband owned a pig slaughterhouse.

Of course, Great-Grandmother was very strict. “When she asked us to do something, that was it,” Nishihara said. “She didn’t like to repeat herself, and everyone got disciplined when they didn’t follow as she asked.”

At the tent city, Tran tried to assert herself. She told her family that she was “too old to wonder” what would happen to her. Still, she reminded little Ha and the other youngsters to mind “that you do what the big American men tell you. We are their guests.”

Tran had pulled through the harrowing boat journey — fleeing in a 20-foot boat with 14 members of her family from their island — famous for fish sauce production — to Vietnam’s open seas. They had been rescued by a Navy ship that transported them to Guam, and from there, they relocated to Pendleton.

But in Oceanside, after dark, the frigid temperatures and winds blowing over the makeshift shelter chilled her bones. She wrapped herself in wool, protected by a rosary. But she caught pneumonia. It was June, and in a matter of days, Tran’s heart stopped beating.

Her great-granddaughter would not leave her side until the adults bid a last goodbye — signing papers allowing her to be buried at the nearby Eternal Hills.

On a morning with a soft breeze, that little girl all grown up locked hands with her own daughter, bending over a grave.

“See there — Anna is her saint name. That’s why we all have it as our saint names,” she explained to the 12-year-old, Summerrose. She read the engraved words, “Anna Tran Thi Nam.”

Nishihara, 45, is a nurse practitioner in the suburbs of Fresno, where her clan settled post-Pendleton, and where her parents found their first American jobs: picking chiles on a farm.

While growing up in California’s Central Valley, she thought she’d be a pediatrician. But discouraged by crying children, she ended up working in urgent care.

She is haunted by her great-grandmother’s last days in the tent city — spent desperately longing for a sponsor who would enable the clan to leave the camp.

“I have always thought — if we never left Vietnam, she would have lived longer,” she said of her great-grandmother. “These are the things we do to stay alive when what you know of your country is dying.”

Nishihara has only fleeting memories of Vietnam, unlike Lam, who has returned to her birthplace four times — once bribing a guard for a peek at her old home, transformed into a post office headquarters.

Lam took over Vien Dong, popular in Orange County’s Little Saigon for its salty, northern Vietnamese cuisine and founded by her uncle, Tony Lam, the first Vietnamese American elected to political office in the U.S.

On a recent day, he visited her at lunch, their heads together, sharing old stories. They were joined by Lam’s husband, Hung Hoang, whose family also sought refuge at Camp Pendleton. They were children in the same sprawling tent city, but they didn’t meet until nearly two decades later.

“I’ve been looking for her all my life,” Hoang told Lam. Their eyes met, the spell breaking when Tony Lam launched into a patriotic song, a call to his youth.

Julie Lam touched her husband’s arm, then her uncle’s hand, nudging him to drink a steaming tea.

“We are Americans now — we are so grateful. But the Vietnamese are survivors because of one thing — family,” she said. “Never mind the distance. We always try to find a way to stay together.”

The 9-year-old boy peeked out from his tent, ready for play. He raced to find his new friends and, grabbing pieces of cardboard, they headed for the hills, sliding down for hours.

“We would never tire of it,” Tony Strom says of his stay at Camp Pendleton, which began when he and his younger sister arrived with their mother, a single parent, the night of April 30, 1975.

Read more»

An-My Le remembers the “empty sort of pain” of being at the Pendleton tent city without her mother.

“Everyone at camp had their moms. We were lost without ours — we were trying to figure out what to do as a family without her,” Le, then 15, says.

Read more»

Behind this story: Journalists share their experiences

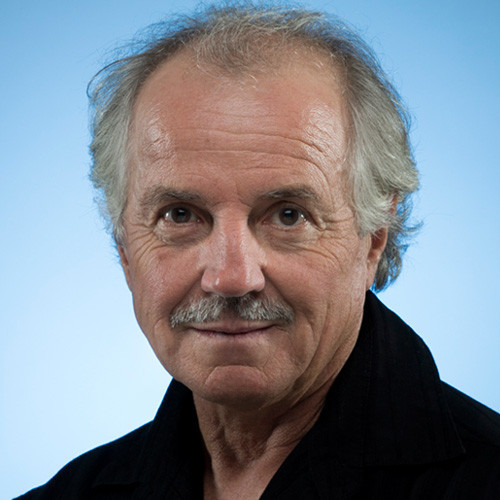

Anh Do, reporter

Forty years ago, my parents told me to prepare for a trip to the seashore. Excited, I rushed to get my plastic pail. What I did not know: we were about to cross a bigger ocean, heading for the promise of America. My father's work as a journalist allowed him to find valuable contacts among foreigners — with a doctor helping us get seats on a flight bound to leave Saigon on April 26, 1975. We landed in Guam, then onto this sunbathed land known as Southern California. Educated in French, I spoke no English. My siblings tagged behind me. My mother carried an unborn child inside her, soon to be my youngest sister. We arrived at camp, searching for warmth and some kind of safety amid chaos.

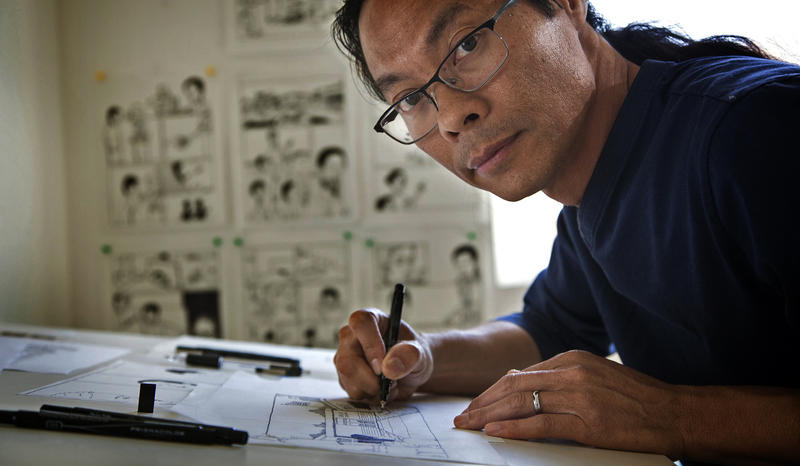

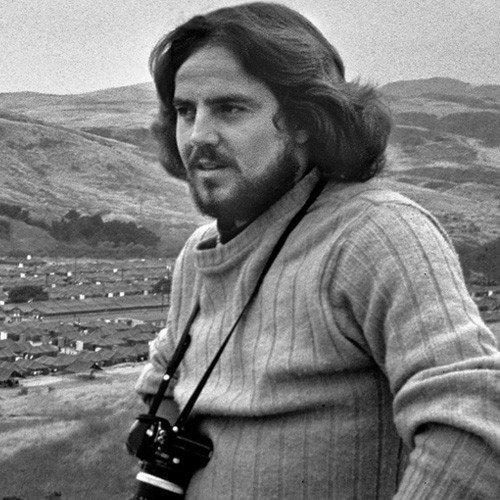

Don Bartletti, photographer

Forty years ago, I worked at my first newspaper job at the Vista Press in San Diego County. The Vietnam War had come crashing to an end — and I asked my editor if I could document the frantic arrival of the refugees crowding Camp Pendleton. Only four years before, I was an Army Infantry 1st Lieutenant commanding convoys of ammunition and helicopter fuel on jungle roads. Now I focused my Nikkomat camera and 55mm macro lens — equipment I bought at the Army Post Exchange in Vietnam — and walked through the tent city. I was stopped in my tracks when I gazed at the most beautiful woman I've ever seen: Tran Thi Nam, age 109. The lines that defined her astonishing age were all but cheek to cheek with the porcelain-smooth face of her 5-year-old great-grandaughter, who leaned on her wheelchair. I photographed the two, never knowing if I would see the child again. Until this April.

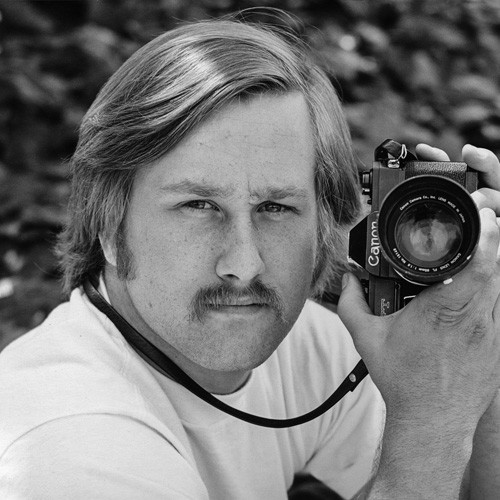

Don Kelsen, videographer

Forty years ago, I was the community relations photographer at Rio Hondo College in Whittier, California. I drove to the windswept refugee camp near the coast and saw rows of children sitting on bleachers. A group of theater students from our school had ventured to Camp Pendleton that May morning to entertain the new population of Vietnamese arrivals. The boys and girls were curious, friendly, sharing easy laughter as the performers staged their skits. I recorded some of the day's events for later publication. I had served in Vietnam, in the infantry with the Army's 101st Airborne in 1969, when battled raged as deaths mounted. In 1975, I soon had a different experience with the Vietnamese.

Additional Credits: Digital Producer and Developer: Evan Wagstaff.

Did you immigrate to the United States after the Vietnam War? Share your experience

What did you or your family bring with you on the journey to America? Do you still have it? Comment below or post to Twitter or Instagram with #VietnamToAmerica. Don't forget to post the photo.

Share your experience

What did you or your family bring on the journey from #VietnamToAmerica?

“My mother grabbed a pile of photos she had carefully saved over the years to document our family story. Ma remembered she was lucky to take 2 ounces of gold and some wedding jewelry — part of her dowry when she married my father in 1964.”

— Anh Do, Los Angeles Times reporter