The gray rubber dinghy that carries Huda Malak, pregnant with her first child, sags to sea level as it approaches Lesbos. The overloaded raft has been taking on water since it launched from a crag off the Turkish shore, about six miles away.

The 18 Syrians on board desperately try to bail water from the sinking craft. Weight, they need to shed weight. They start jettisoning backpacks that hold most everything they still own. A trip that should have taken 45 minutes has lasted double that, and they are still a mile from the Greek island.

Suddenly, Malak’s husband, Tarek Sheikh, stands up.

“I’m doing this to save you, our child, and everyone on board,” Sheikh tells her.

Then he jumps overboard.

His weight makes the difference, and the raft chugs toward land as Malak looks back to where her husband disappeared into the Aegean.

Finally, the boat makes one last thrust and scutters onto a pebble beach.

“Thank God, we are alive!” shouts Firas Gharghoori, a thick, compact man in shorts and a straw fedora, kneeling on the polished stones in a prayer of gratitude.

The new arrivals begin to wander away from the shore, but Malak remains. She crouches with knees bent, face cradled in her hands, her eyes focused on the sea. Fellow migrants approach to offer support to the 23-year-old schoolteacher, their elation at having made it to Europe tempered. She waves them off.

Without warning, Sheikh’s younger brother, Mohammed, takes off his shirt and plunges into the surf in a bid to rescue Sheikh — soon followed by a grizzled Greek restaurateur who has wandered to the scene. The Greek later swims back, his leg bloodied from the rocks. He gamely tries to maneuver a white paddle boat to sea as a makeshift rescue craft. It doesn’t get very far.

A Greek coast guard vessel appears offshore, but far from where Sheikh disappeared. Gharghoori frantically signals at the cutter to move to the left. A coast guard officer in aviator sunglasses, who is in radio contact with the cutter, arrives in a pickup. In broken English, he tries to calm everyone. A few minutes later, he approaches Malak and gives the thumbs-up sign.

Her husband, the hero of the gray rubber boat, is safe. His brother has been rescued too.

This year, more than 2,500 refugees and migrants have died trying to reach Europe in an armada of flimsy rubber dinghies and rickety fishing boats.

Tens of thousands of others are willing to take the risk. But they make it.

Men jump out first, giving a hand to women and children, who sit low in the middle of boats that are inevitably crammed with far too many passengers. Backpacks and shoes are tossed to the beach in the faint hope of keeping them dry. Some flip their life jackets in the air, like soccer players shedding their shirts after a goal.

Edward Mardini, his trousers and shirt plastered onto his thin frame, liberates a phone from several layers of plastic wrap and tries to keep from dripping on it as he dials Damascus.

“Father, we made it to Europe!” Mardini shouts into the phone, tears welling behind his spectacles. He fires a celebratory safety flare into the air, sending red sparks into the azure sky.

His 5-year-old son, Michel, keeps blowing the red whistle he was given when boarding the boat, seeming to find some comfort in the repetitive act.

Nearby, Greek foragers who’ve been waiting on shore move in with quiet efficiency, grabbing the outboard motor and dragging it up the beach like rough treasure.

The narrow ribbon of water between Turkey and Greece where Homeric protagonists once sailed to immortality has become a heavily traveled thoroughfare in the depopulation of Syria, a nation whose relentless destruction has touched off one of the biggest waves of human migration since World War II.

More than half of Syria’s prewar population of 22 million is adrift, including 4 million refugees who have fled abroad and 8 million Syrians forced from their homes but still living in the war-ravaged country.

Tens of thousands of Syrians, along with migrants from Afghanistan, Africa and elsewhere, have surged toward Europe seeking refuge in such relatively generous nations as Germany and Sweden.

Where have Syria’s refugees gone? »

The mass exodus has created an anarchic human caravan that appears beyond control. Clashes have broken out with authorities from the Greek islands to Budapest to the German-Danish border, creating a crisis for bewildered European policymakers who are throwing up walls and razor wire and dispatching riot police along porous frontiers.

This year alone, close to half a million migrants have crossed the Mediterranean and reached Europe, according to the International Organization for Migration, a Geneva-based intergovernmental body.

Almost 350,000 migrants — a nearly eight-fold increase from all of 2014 — have arrived by sea in Greece, a critical hub in the new migration because it affords relatively easy access to the rest of Europe from Turkey, which borders Syria and connects with land routes to Asia.

They come, like the Mardini family, with a cellphone, a backpack or two and their remaining life savings in U.S. dollars stashed away in their clothing. Many have sold everything to pay smugglers to cross from Turkey, and to cover additional smuggling and travel fees farther on.

Doctors and teachers, engineers and housewives, they board boats from secluded coastal strips in Turkey and aim for the rocky shores of Lesbos, Kos and other nearby Greek islands, the distant vessels appearing as black specks on the horizon. From the beaches of Lesbos, many face a 40-mile walk to the nearest processing center, because Greek officials restrict access to buses or taxis in a failed attempt to stem the illicit arrivals.

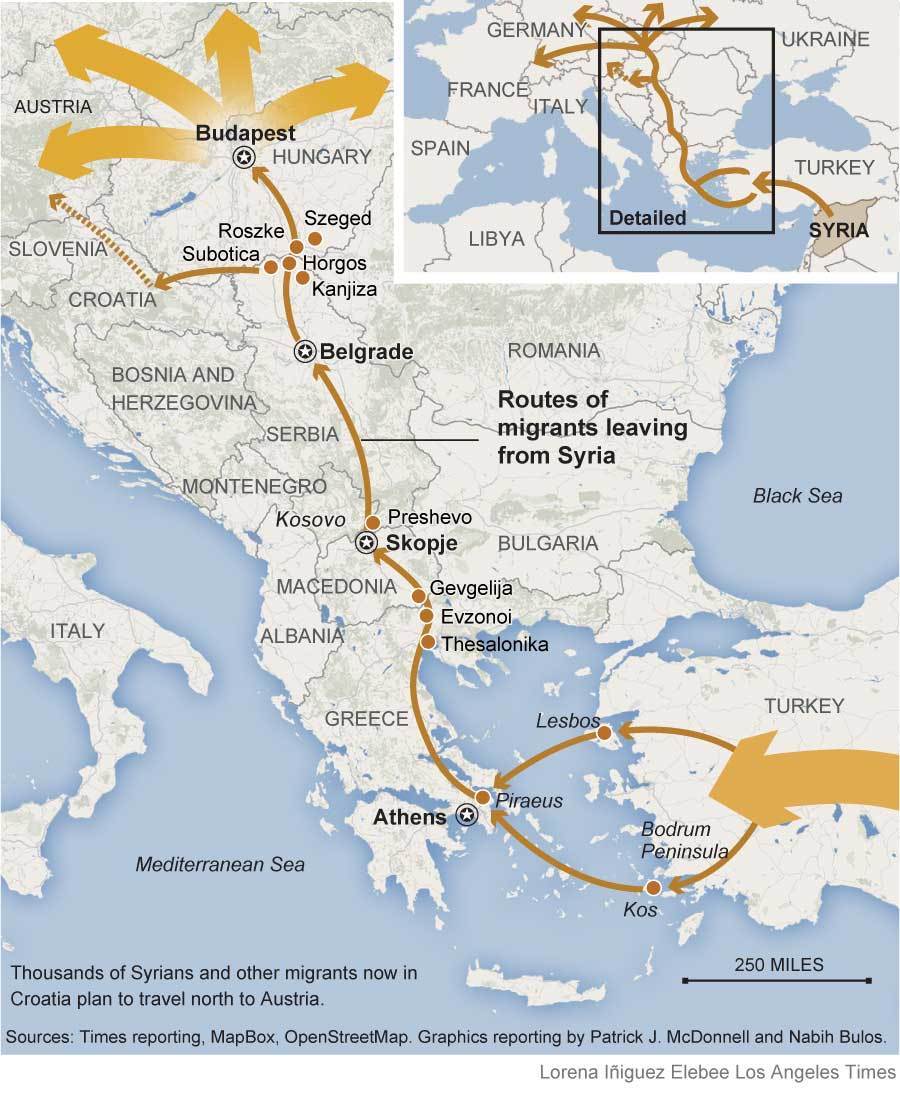

The refugees often spend days awaiting Greek permission to leave the islands before boarding ferries for Piraeus, the port of Athens, and then embarking upon a new and sometimes perilous journey through the Balkans and on to Hungary, Austria and Germany.

The Mardini family began their odyssey in Bab Touma, a mostly Christian district in the Old City of Damascus that is a frequent target of insurgent shelling. But before that, they’d already moved twice from war-battered suburbs to flee bombardment.

“My older boy was having a lot of problems because of the war, the shelling,” says Mardini’s wife, Sara Azar, standing on the beach and cradling her 1-year-old son, Mark, who is still wearing his bright orange life jacket. “He was starting to stutter. He was so afraid.”

Mardini quickly calls the smuggler in Turkey who’d arranged their passage on the boat, reading a code that will release the smuggler’s fee from a kind of escrow account. It’s a rare consumer protection measure for clients who cough up between $800 and $1,200 per head for a trip that costs $17 on a legal ferry. With payment on arrival, smugglers theoretically have a financial motivation to ensure that their clients reach the other side.

“Abu Hussein,” he tells the trafficker, using the man’s nickname. “I cherish Allah, the prophets and you!”

::

After arriving on the coast, clusters of bedraggled migrants soon begin hiking up the steep hills, passing tourist hotels, cafes and swimming pools on the 40-mile trek to the island’s capital, Mytilene, where ferries embark for the mainland.

Along the winding road, they doze beneath trees and in grassy clearings, often in breathtaking settings overlooking the Aegean, with the Turkish coast shimmering in the distance.

Groups soon thin out as the younger, healthier walkers take the lead, leaving behind the elderly, the infirm and those with small children. The summer sun is unforgiving; temperatures soar above 90 degrees.

“Please, a ride, just for a short distance?” one elderly Syrian woman, dressed head-to-toe in black, implores a motorist at a particularly difficult uphill stretch. “Bless you!” she says after being given a one-mile lift up the hill. “Bless you!”

At the fishing village of Skala Sykaminias (permanent population: 140), clusters of new arrivals file by Our Lady the Mermaid Orthodox church, past port-side tavernas with drying octopus tentacles hanging outside and fishermen mending nets and unloading the day’s catch. Nearby beaches are littered with deflated rafts and discarded life jackets.

Tourists and townsfolk have gotten used to the apparitions.

“Of course we feel bad for them; we see pregnant women and the elderly among them,” says one restaurant owner as she serves coffee and breakfast to tourists. “They don’t hurt anyone. But it makes the visitors uncomfortable.”

As she speaks, another raft filled with migrants glides ashore a few hundred yards up the coast, within view of the coffee sippers.

On a recent day, an Afghan woman with polio was stranded in the village. Her fellow Afghans advised her to stay behind in the hope that someone would have pity on her. She sat for hours outside a church, forlorn. Finally, a Dutch tourist couldn’t take it anymore. She borrowed a car and drove the woman part of the way to a makeshift camp, signaling her passenger to duck down in the rear seat to avoid police, known to bust anyone giving lifts to migrants.

Sources: Times reporting, MapBox, OpenStreetMap. Graphics reporting by Patrick J. McDonnell and Nabih Bulos. Graphic by Lorena Iñiguez Elebee, Los Angeles Times.

Many of the refugees stop at a mini-market for water and snacks before proceeding up the steep hill leading out of town. At the market, Rami Kanbar, 29, is provisioning for the trek along with his boat-mates.

Kanbar, wearing a hooded gray University of Colorado sweatshirt, says he left Aleppo, his hometown, where he had worked as a volunteer emergency medical technician in a city split between government and opposition forces. He came under suspicion because he provided aid to victims on both sides of the conflict, he says, his voice cracking with emotion.

“My only crime is that I was helping people,” he says.

Raed Mutleb, 27, wearing black cargo pants and a faded pink T-shirt emblazoned with the Calvin Klein logo, makes his way along the beach with metal crutches — the result, he says, of a bullet in the spine during the early days of anti-government protests in Damascus in 2011.

Accompanying him are several relatives and friends from the Syrian capital, including reed-thin Thalal Massoud, 15, who suffers from a genetic condition that has left his leg muscles atrophied.

Leading the group is Massoud’s cousin, Mohammed Massoud, 26, a friend of Mutleb who studied French literature at the University of Damascus. The war cut short dreams of graduate study, and he is headed to Germany.

On the raft from Turkey, Mohammed Massoud says, he faced a wrenching dilemma.

“If we capsize, I can swim, I will survive. But you start asking yourself: Whom do I save?” he explains. “These are my loved ones, my body. Do I save my eyes?” He points to Thalal. “Do I save my heart?” Now he gestures to a female cousin, who doesn’t know how to swim. “Whom do I save?”

The group moves on. As they proceed in single file, the able men take turns carrying the younger Massoud.

Last in line is Mutleb on his crutches, moving slowly but never faltering.

::

In Lesbos’ main migrant camp a few days later, drying clothes hang from the chain-link fence encircling what used to be a park. Clumps of human waste lead to a hole in the fence that is a preferred entrance — no police stand guard here. The patches of grass and cracked concrete house multicolored tents bought for a bit more than $30 from locals cashing in on the migrant boom.

Mutleb, still wearing his Calvin Klein T-shirt, is washing at the communal faucet along with several companions from his raft. He hobbles about on his crutches in the mire of the camp.

On the streets of the tent city, enterprising migrants have jury-rigged traffic-light control boxes to siphon off electricity and charge their mobile devices. Several men live in a pair of abandoned sedans. Others sleep through the afternoon swelter amid a pile of ancient Greek and Roman columns, remnants of Lesbos’ illustrious past as a trading hub and center of learning, the birthplace of Sappho, the ancient lyric poet and proto-feminist.

“I’m just happy to be getting out of here,” says Amina Anas, who arrived with two children on the same boat as Mardini and his family.

She has finally received the official police paper allowing her family to leave on the evening ferry to the port of Athens.

Anas is traveling with her friend Wafaa al-Tarawiyeh, a heavyset woman with an unbroken smile whose son, Mohammed, 10, is seldom seen without a soccer ball.

“We’re going to Germany, no matter what my mom says,” he declares, after his mother has explained that their ultimate destination is uncertain. “In Germany they play the best football!”

::

“I was so angry when Tarek jumped in the water,” Malak says of her husband, whom she married in March. “But now I’m very proud of him.”

Malak says she deeply feared the frequent aerial bombardments back home in rebel-occupied northwest Syria. “My students would laugh and tell me not to worry, that the planes weren’t that close,” she recalls.

Tarek Sheikh, 32, a former contractor in the government-held city of Latakia, wanted to avoid military service for him and his younger brother in a nation where fighting-age men are a sought-after commodity — and have an alarming casualty rate. It is clear that Sheikh feels the weight of responsibility for this risky excursion to Europe.

After Sheikh was rescued, the couple was reunited at a makeshift shelter behind the Captain’s Table restaurant in Molyvos, a tourist town in Lesbos, and have made the trek to the Greek border with Macedonia with nearly 40 other people.

After a final two-hour walk through corn and sunflower fields, guided by word of mouth and GPS readings on cellphones, they arrive in a forest clearing. It is little more than a tree-shrouded landfill, soiled with discarded shirts and dresses, worn-out shoes, half-consumed food, pill bottles, torn-up documents.

They wait patiently as mosquitoes, fleas and giant flies feast on them. One girl combs the blond hair of a Barbie doll pulled from her pink backpack.

Near the international border, Greek police in military uniforms hold the migrants back, issuing each group handwritten numbers on scraps of white paper, like tickets on a deli line, to stagger their illicit entry into Macedonia. Finally, at mid-morning, it is their group’s turn.

An hour’s hike takes them to the weathered train terminal in Gevgelija, a Macedonian casino town turned migrant way station.

As Sheikh and Malak describe it later, the train north to the Serbian border was packed and sweltering, hardly offering room to breathe. Then, they were turned back three times as they tried to sneak through the forest into Serbia. After finally managing to cross, they were caught and separated, to Malak’s distress, before being reunited and allowed to move on. They rested a few days in Belgrade, the Serbian capital.

The next obstacle: Hungary, notorious as a nation where many migrants and refugees end up in primitive detention centers. Hiding from border police, Malak says she heard the rhythmic rumble of a helicopter. “That made me think of Syria, the bombings,” she says.

After several failed attempts, the three crossed clandestinely into Hungary. A smuggler drove them to Austria, while another ferried them to Germany. And then, the last stage: a train to France.

During their 15-day odyssey, Malak and Sheikh crossed seven borders, covered more than 1,500 miles in boats, trains, buses, cars and on foot. Their raft had almost capsized in the Aegean, they got stuck in squalid camps, gloomy forests and along remote railroad tracks. They dodged border police and haggled with unscrupulous smugglers, and exhausted their savings.

But, finally, they — like so many others who have lost so much, and have risked so much — made it to western Europe, the new promised land.

::

For now, the couple has settled in the bustling French city of Lyon, along the Rhone, at the foot of the Alps. It is a mecca for students, tourists, gastronomic connoisseurs and outdoors enthusiasts.

With its old city lined with restaurants and outdoor cafes, and its proximity to some of France’s most storied wine country, Lyon attracts many seeking an urban lifestyle less frenetic than that of Paris and other big European cities. The city also has a significant Arab minority, mostly from north Africa.

The couple was drawn here because Sheikh’s older sister, Shatha, has lived here for years, pursuing a doctorate in science and an academic career. Sheikh’s parents arrived earlier this year from Latakia, on Syria’s Mediterranean coast. The extended family shares the sister’s neat, one-bedroom flat in a middle-class neighborhood where Arabic is widely spoken.

Guests are welcomed in the family apartment with tea and sweets. Her in-laws are extremely protective of Malak, who lovingly cradles her husband’s curly-haired 1-year-old niece, Shaymaa Alice.

Sometimes the couple strolls, holding hands, in the sprawling park known as Tete d’Or (Golden Head), a broad expanse of forests, fields and a lake at the edge of the city featuring scenes reminiscent of an impressionist canvas.

As the family completes political asylum paperwork, Sheikh is looking for work in construction. Malak wants to find some kind of job and continue her studies in English literature, her focus at the University of Aleppo.

In a neat script, Malak writes one-act plays in English, allegories of her life in Syria.

The text of one, “The Magic River,” was lost in a backpack when the family jettisoned much of their belongings from their foundering raft. “It’s still in my head,” Malak says.

Another drama, titled “The Closed Door,” is an internal monologue featuring a single character, Adam, who is locked in a closet. When he manages to open the door, and light streams in, dread of the unknown outside paralyzes him.

“I’ll stay here; it is stable here,” Adam tells himself. “At least here I can see the place around me and can hear myself.” But he fears he may suffocate inside.

Malak seems more confident now, filled out, a young woman flashing a bright smile, no longer gripped by uncertainty. For the time being, she says, the family will remain in France. She never liked traveling, she confides with a grin.

Special correspondents Nabih Bulos and Liliana Nieto del Rio contributed to this report.

About this series: This is the first in a series of reports on the greatest trans-national human migration since World War II. How we reported the series and reader reaction here »

A Syrian mother clings to shreds of hope for her family stuck in Turkey »

A group of Syrian women struggle to make a new life in rural Egypt »

Additional Credits: Video: Nabih Bulos. Digital design director: Stephanie Ferrell. Digital producer: Evan Wagstaff. Lead photo caption: Migrants landing in Lesbos, Greece.