| GROSS SCHNEEN, Germany

Sometimes he sneaks the old family photo down to his room because he likes it so much, even though it was taken long before he was alive, and even though it’s not his family. At least, not the one he was born into.

He finds comfort in the faded tableau: the young couple with their two small kids, smiling happily 35 years ago in what was then West Germany — a world unimaginably removed from the one in which he grew up. But Germany is now his home too, and the people in the picture have become surrogates for the loved ones he left behind.

His parents and two younger siblings are still in Syria, and he worries about them every day. They fire messages back and forth on WhatsApp; they talk on the phone when they can. He knows his family hides things from him — like the time his mom and sister were shot and wounded in front of their house, not long after he said goodbye. They only told him about it weeks later.

His parents want him to concentrate on building a life for himself in this strange new land, with its unfamiliar customs, its difficult, alien tongue. And if they can’t be there for him, they’re glad the couple in that long-ago photo are. Since the day Eva Linkersdoerfer, now a cheerful 70-year-old, spotted Mustafa Kawsara in a school gym packed with refugees, she and her husband have taken him under their wing, offering advice, a listening ear, and a warm, comfortable room here in the village of Gross Schneen.

If anyone who’s had to flee his homeland and abandon all he holds dear can be counted as lucky, Kawsara knows he’s been lucky — twice.

He’s thankful to have made it to Germany after an exhausting, often harrowing trek across Europe this summer. Syria’s brutal civil war no longer threatens him directly.

But he knows he’s had another narrow escape. Instead of sitting in the Linkersdoerfers’ home, gazing wistfully at their family portrait, soothed by the peace that floods the tidy rooms, Kawsara, 22, could be living a drastically different life right now, right here, in the very heart of Germany.

He could be sitting in a crowded, chaotic camp just two miles down the road. He could be feeling lost, hopeless, alone. He could be in Friedland.

::

Set in a charming landscape of verdant fields and wooded hills, the town of Friedland (pop. 1,200) prides itself on being a haven for those in need.

For 70 years it has hosted a refugee camp, whose first occupants were some of the millions of ethnic Germans expelled from Eastern Europe after Hitler’s defeat. The main street is Heimkehrerstrasse: “Returnee Road.” On a hilltop high above the town, four immense, jagged concrete slabs stand as a monument to the original refugees, with plaques admonishing future generations to safeguard freedom and human dignity.

Those who have found shelter in Friedland over the decades include people escaping violence in Vietnam and the Balkan conflicts of the 1990s.

But this is now a camp, and a town, overwhelmed. Friedland’s patience and resources are under intense strain by a volume and speed of new arrivals that no one was prepared for.

The same is happening all across Germany. More than 750,000 asylum seekers, many of them Syrians, have crossed into the country in 2015, part of the biggest mass migration Europe has seen since World War II. The total could rise to 1 million by year’s end. The near-euphoria of the summer — when Germans greeted arriving refugees with applause, when they basked in the international praise heaped on their country for throwing open its doors — has been supplanted by some harsh realities and hard feelings.

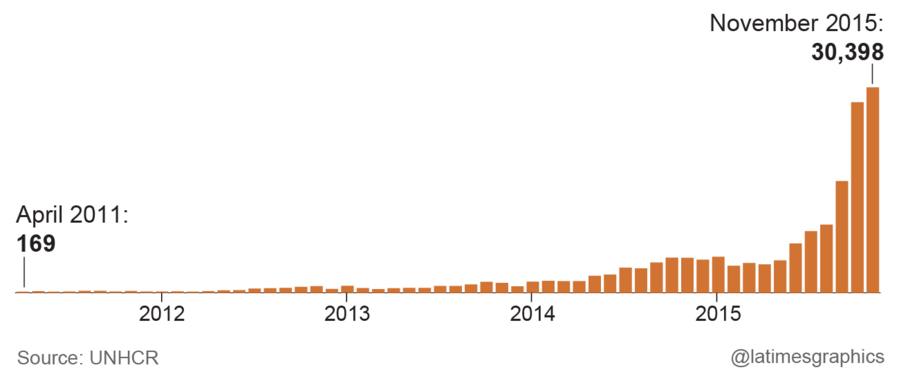

Monthly Syrian migration to Germany

Chancellor Angela Merkel’s once-stratospheric approval ratings have dropped as members of her own center-right party, the Christian Democratic Union, angrily criticize her open-door policy. Far-right groups counter her mantra of “We can do it” with the slogan “The boat is full.”

Friedland hasn’t been immune. In August, residents found anti-refugee flyers from the neo-Nazi National Democratic Party stuffed into their mailboxes. Stickers slapped on lampposts declared “Maria, not Sharia”: the Virgin Mary, not Islamic law.

One of the problems is that Friedland’s camp, in the middle of town, was designed for 700 to 900 people. A couple of months ago, it held 3,500, or maybe even 4,000. No one knows for sure, because they came so fast they couldn’t be properly processed. Almost overnight, foreigners outnumbered local residents three to one.

The camp’s population is currently about 3,000, which means that Heinrich Hoernschemeyer, the camp director, still has to pick his way to his office past men, women and children stretched out on mattresses and cots in the hallways of the administration building.

“At the moment our biggest priority is that everyone has a place to sleep,” he says.

Rooms meant for four people now house eight or more. Classrooms and TV lounges have been turned into sleeping areas, which increases the number of beds but takes away leisure facilities for the camp’s inhabitants, many of them single young men who chafe at the enforced idleness.

Fights are not uncommon. Police have been called in to break up brawls, which often erupt in the long lines for food. It can take up to two hours to get into the cafeteria, past the German security guard in the flak jacket and rubber gloves who sits warily behind a thick sheet of plexiglass, stamping everyone’s ID cards.

The primary activity in the camp is waiting. For meals. For the chance to sift through mounds of donated clothes, hoping to score shoes that fit. For some indication of how long you’ll have to stay in Friedland. For your interview with a social worker, your appointment with a counselor, your court date for your asylum application.

Regular procedures of registration and orientation have been upended, offending the German penchant for order and efficiency. Only recently was Hoernschemeyer’s overburdened staff able to produce a complete list of everyone living in the camp.

Syrians make up the largest group. Then come Iraqis and, after them, Afghans, Eritreans and Pakistanis.

The camp’s official capacity figure now seems a mockery.

“We’re not going to get down to 700. That’s just unrealistic,” Hoernschemeyer says. “But if we could just get down to double the maximum, that would be good.”

::

Susanne Schneider lives across the street from the camp’s main entrance, in a modest home with a small, manicured lawn. Behind her friendly demeanor lies a struggle between her sympathy for people who have run for their lives and her aggravation over the disruption some of them are causing.

The camp’s inhabitants are free to go in and out. They take walks through town, past the parish church, the local supermarket, the fast-food place, the Jehovah’s Witnesses on the sidewalk handing out literature in Arabic, the railway station, the neighborhood pub. Farther on, they cross the little bridge over the Leine River, which gently winds through the states of Thuringia and Lower Saxony.

Women in head scarves shout after children on bikes. Young men in twos and threes swig soda, sometimes beer.

There’s little interaction, friendly or hostile, between the foreigners and the locals.

But there are complaints. Residents say they’ve come home to find their apple trees picked clean. Or their kids’ bikes and toys stolen, after being left outside with the small-town trust that everyone is used to. There’s the trash in their yards, the noise at night, the commotion when police are summoned to the camp.

Schneider feels like she can no longer keep her two dogs out front.

“The people walk along the edge of my yard, along the fence, and the dogs bark at them. I’ve gathered a bushel basket full of sticks out of my yard that have been thrown in there by passersby...They just hit them,” she says.

The family-run Edeka supermarket, on Heimkehrerstrasse, is one of the few places where local residents rub shoulders with the new arrivals. The number of customers has doubled over the last 12 months. A year ago, the store sold 40 loaves of bread a day; now it’s 200, manager Tanja Gonschior says.

But the market is hardly making a killing, Gonschior says during a break in the peach-colored staff room.

The newcomers mostly buy staples like oil, beans and flour, which don’t carry high profit margins, says Gonschior. Sometimes they rip open merchandise to see whether it’s sugar or salt, ketchup or barbecue sauce, because they can’t read the German packaging. A few helpful labels in Arabic have helped cut down on that practice.

But the store also has been hurt by the fears of some of the local residents. They tell Gonschior they avoid buying fruits and vegetables now for fear of catching diseases from refugees who poke and prod the produce, but haven’t undergone medical screenings in the camp.

Photographer's journal: A look at Europe's migrant crisis

Photographer's journal: A look at Europe's migrant crisis

“I tell them I take all those things home and I eat all those things, and I don’t get the flu,” says Gonschior, 40, an affable woman with tattoos of stars behind her multiply pierced ears. “Who tells me that German people are very hygienic? No one has a paper to show me that says, ‘I’m clean.’”

Worried residents raised the health issue at a tense town hall meeting in October attended by more than 300 people. They also demanded to know how long the camp would remain overpopulated.

Andreas Friedrichs, the mayor for the greater Friedland area, says he’s pleaded to the federal government in Berlin for more resources, but they’ve been slow in coming.

“I told the German interior minister that you can break even a good horse. He said what he always says: ‘We’re doing everything in our power.’ And I responded, ‘Then please do it quickly.’”

Friedrichs pauses, then reaches for another metaphor to describe Friedland’s predicament: “Our snorkel is not as high as the tsunami is.”

::

Kawsara arrived in Friedland at the beginning of August. He was shocked by the camp’s conditions, but the overcrowding ended up working to his benefit.

He’d left Syria in May. He was only a few months away from earning his law degree, but the situation in Idlib, his hometown, had become so dire, with young men shanghaied into fighting for one side or the other, that sticking around to get his diploma was folly.

Two months of hard travel took him from Turkey to Greece, through Macedonia and Serbia, across Hungary and Austria, and finally to Munich, in southern Germany. From there, he took a train to the town of Neubrandenburg, north of Berlin, where he had a contact. But at the Neubrandenburg railway station, he decided to turn himself in to police. It was close to midnight.

“I said, ‘Hello, I am Syrian.’ They said, ‘You are welcome,’” Kawsara recalls. They started peppering him with questions, but then, noticing his exhaustion — he hadn’t had a proper night’s sleep for a week — they asked if he needed a nap. When he nodded, they led him to a bed in an unlocked jail cell.

“It was the most beautiful place I ever slept in,” he says.

He was sent to Friedland a couple of days later, but officials at the camp said it was full. After staying only a couple of hours, he and some other new arrivals were bused to a hastily prepared overflow facility: the gym at the Carl Friedrich Gauss School, a public campus here in the village of Gross Schneen.

It was an improvement, though scarcely paradise. Scores of people slept in the same room, in row upon row of cots.

He felt glum that first day in Gross Schneen, and sat with his eyes downcast, his thoughts far away. The authorities had taken away his cellphone as part of their security investigation into his background, and he had no way of communicating with his parents and younger siblings in Idlib or with his two older brothers, who’d fled Syria before him, in England and the U.S.

A friendly, eager volunteer asked if she could help. She spoke to him in English, which he could speak, too, having learned some at school and even more from Taylor Swift songs and favorite films like “Fast and Furious.”

The woman took him to the local police station to inquire about his phone and his passport, which had also been confiscated. Yes, the items were in official custody. But it would be some time before he could get them back.

The next morning, the woman — it was Linkersdoerfer — turned up at the school again and gave him a present: an old cellphone and a SIM card so that he could call his anxious family, who had had no news of him for days.

After that, Kawsara and Linkersdoerfer were constant companions. A retired schoolteacher, she came to the campus every day to give German lessons to the refugees. He was her assistant, his English and Arabic bridging the gap between her and her pupils.

Away from the classroom, the two of them would chat for hours about everything: politics (he wants Syrian President Bashar Assad to go, but without violence), religion (he’s Muslim, she’s an atheist), gender equality (they’re both in favor), gay rights (she’s for, he’s against). Ever the teacher, Linkersdoerfer schooled her young new friend in aspects of German culture, like punctuality and meticulousness, and researched how he might continue his studies in Germany.

After heavy rains flooded the gym in the middle of August, forcing all the refugees there to relocate to another school a few miles away, Linkersdoerfer made a snap decision.

“One day my husband came home from work, and I said: ‘Mustafa is now here. He is living with us,’” Linkersdoerfer says. “I knew after so long together, 40 years, that he would say OK.”

Wolfgang Thyssen-Linkersdoerfer — he adopted his wife’s last name — didn’t blink. He and Eva are proudly pro-refugee and loudly left-wing. A sticker on their mailbox proclaims, “A bed for Snowden,” proclaiming their willingness to offer sanctuary not just to Kawsara but to Edward J. Snowden, the former U.S. national security contractor who leaked highly classified documents.

Newly retired from his engineering job, Wolf, 63, has no patience for fellow Germans who think their country should turn refugees like Kawsara away.

“Are we supposed to shoot them, or sink their boats, or build a wall?” he says. “We’re a rich country, we’re a big country….We absorbed East Germany, so why is this a problem?”

::

In September, Kawsara stood before two dozen teenagers at the Carl Friedrich Gauss School, whose gym he’d lived in while the students were off on their summer break. Their teacher, Tarek Zaibi, had invited him to come speak to his class.

“I wanted to help them get rid of their prejudices,” Zaibi says. One girl had told him that the asylum seekers she’d seen looked too normal to be people fleeing a war. Why weren’t they missing limbs, or marked with bullet wounds?

Zaibi had asked Kawsara if he wanted any topics to be off-limits. Kawsara said no. The students’ questions to him that September morning were personal, direct.

How can a refugee afford a smartphone?

How much did he pay to get to Germany from Syria?

Does he have a girlfriend?

He explained that nobody dared make the trek through Europe without a GPS-enabled smartphone, for navigation and for communicating with folks back home. It was a lifeline.

His own two-month odyssey cost more than $4,200, including $2,150 for the hazardous sea crossing from Turkey to Greece and an additional $1,600 for a smuggler to drive him and others in a jam-packed van across Hungary into Austria without stopping, a journey of several hours.

And no, he doesn’t have a girlfriend at the moment, but he did before.

In Syria, he was shy and had few friends. But negotiating his way through Europe, on his own, boosted his confidence. He strikes up conversations easily with strangers now, and is determined to adapt to his new surroundings.

He sees in Germany the possibility of life the way he wants to live it: in a democratic, free society where people play by the rules. He likes it that people here are “punktlich” — punctual.

At the end of October, he began German language classes, augmenting what he’d learned at Linkersdoerfer’s side. Like a concerned parent, she drove him to his first day of school in Goettingen, about eight miles away.

Both of them were fuming slightly over the prospect of being late because a school official had told them the wrong start time.

“That’s bad,” Kawsara says. “He’s not German.”

“You’re more German than him,” Linkersdoerfer says with a snort.

Within minutes of being dropped off, Kawsara introduces himself to the teacher, a young woman named Marilena Ahnen, and stays by her side as the other students mill about. Like him, they’re mostly Arabic speakers. “You’re my official translator,” Ahnen tells him, in English. He beams.

Recently, he moved out of the Linkersdoerfers’ place to a room they found for him in Goettingen, because they’re planning to shut up their home in Gross Schneen to spend the winter in Spain.

But he still sees them often. They take him to volleyball matches in Goettingen’s big sports arena, where he’s learning to cheer and shout for the home team the way Eva does. He’s met their daughter and son — the two little kids in that family photo he likes so much, both of them now older than he is.

Sometimes, Eva can’t help but ask: “Would your parents have taken me in if I had come to them?”

He ponders. Perhaps not in the same way, he says at last. Their house in Idlib isn’t as spacious. But he has faith in his parents’ generosity; he’s certain they would extend a hand however they could. “There are many ways to help,” he says.

He’s settling into his new life, but he knows he won’t feel fully at ease until his parents and younger siblings are out of Syria. He has recurring nightmares about seeing his mother and sister getting shot, even though he wasn’t there when it happened; about being back in the forest along the Hungary-Serbia border and wondering why, why does he have to make that final push to Germany all over again?

He wakes up, heart pounding. After a few disorienting moments, it dawns on him that he’s in Germany after all, and that he has a second family looking after him now.

A few years ago, the Linkersdoerfers renovated their house, including the rooms he stayed in, which they redesigned with an expanded clan in mind. But their son and daughter have yet to oblige them with the desired grandchildren. “So he is our grandson,” Eva says, smiling and pointing at Kawsara.

“I’m happy to be,” he replies.

His eyes are red.

--

In an earlier version of this story, the name Tanja Gonschior was spelled incorrectly.

---

Design and development: Lily Mihalik. Lead photo caption: Mustafa Kawsara, 22, left his family in Syria in May 2015 to seek a better future. He plans to make a new life in Germany.