Interactive Graphic

Faces to watch in 2014: Entertainment and arts

The Times asked its reporters and critics to highlight figures in entertainment and the arts who will be making news in 2014. From teen actors to media moguls, rappers to classical cellists, here’s who they picked:

|

Ansel Elgort | Actor

Before Ansel Elgort was cast in two of next year's most highly anticipated movies, he had 900 followers on Instagram. Now — just months after shooting the dystopian action flick "Divergent" and the cancer love story "The Fault in Our Stars" — he's up to more than 117,000. Both films are adaptations of bestselling young-adult novels, and if fans of the books turn up at theaters in droves, Elgort is primed to become the next big teen heartthrob. In a way, though, the 19-year-old has been readying himself for the spotlight for years. Growing up in Manhattan, he performed the Nutcracker with the New York City Ballet and attended LaGuardia High School — the performing arts school that 1980's "Fame" was based on. His parents were also in the arts: His mother is opera director Grethe Holby and his father, Arthur Elgort, shot photographs for Vogue. Did your parents' professions influence your decision to be an actor? It was monumental that they were in the arts. My dad was always taking photos of us at home, and even on set — he'd bring us along and stick us in the photos in the background. It was almost the beginning of acting for me, like, "Hey, you go over there and play basketball in the background, and don't even think about the camera." — Amy Kaufman |

|

Natalie Dormer | Actress

Audiences familiar with Natalie Dormer are probably accustomed to seeing her dressed up in royal garb, from the flowing gowns of Anne Boleyn on the Showtime series "The Tudors" to the ornate dresses of would-be queen Margaery Tyrell on HBO's "Game of Thrones." Next November, the 31-year-old British actress will show a different side as Cressida, the intrepid documentary filmmaker and revolutionary in "The Hunger Games: Mockingjay — Part 1," the first installment of the series' two-part finale. "It's such a departure for me," Dormer said, speaking on the telephone from Britain. "At the moment, people think of me in long skirts, with long brunet hair, so [it's a change] to be running around in combat trousers and flat army boots." A role in the blockbuster series, which Dormer will reprise for "Part 2" in 2015, could spell a new level of fame for the actress, who in addition to "Game of Thrones" this year appeared in the Formula 1 racing drama "Rush" and the Ridley Scott thriller "The Counselor." She has also completed work on "Posh," director Lone Scherfig's adaptation of the Laura Wade play about an elite social club at Oxford University, as well as the indie dramas "Fencewalker" and "A Long Way From Home." — Oliver Gettell |

|

Diego Boneta | Actor

Born to two engineers in Mexico City, actor and singer Diego Boneta can thank his parents for a slight miscalculation. At age 12, he begged permission to audition for "Codigo Fama," a singing reality show for children. "After my mom saying to my dad that she knew her statistics and there was no way I was going to make it, they let me go," Boneta, 23, said on the phone from Los Angeles, where he now resides. He came in fifth place, which led to stints on three telenovelas and then appearances on the American TV series "Pretty Little Liars" and "90210." Boneta made his film debut opposite Tom Cruise and Julianne Hough in "Rock of Ages," an adaptation of the Broadway musical, and he's showing no signs of slowing down. He'll next appear on screen in "Pele," a biopic in which he plays the childhood rival of the Brazilian soccer star. The film's release will be timed to this year's World Cup, which kicks off in Brazil in June. Boneta made his film debut opposite Tom Cruise and Julianne Hough in "Rock of Ages," an adaptation of the Broadway musical, and he's showing no signs of slowing down. He'll next appear on screen in "Pele," a biopic in which he plays the childhood rival of the Brazilian soccer star. The film's release will be timed to this year's World Cup, which kicks off in Brazil in June. Boneta has also wrapped the psychological thriller "The Dead Men" and the "Lord of the Flies" remake "Eden," about a downed U.S. soccer team. He'll start shooting the horror movie "Summer Camp" in Barcelona in January. — Oliver Gettell |

|

Gia Coppola | Filmmaker

With the release of "Palo Alto" in the spring, first-time writer-director Gia Coppola will officially usher her family's filmmaking tradition into its third generation. But although she is the granddaughter of Francis Ford Coppola and a niece to Sofia Coppola and Roman Coppola, her mentor and closest collaborator on the film was James Franco, whose short-story collection "Palo Alto Stories" provided the source material. As a screenwriter on this fall's animated hit “Wreck-It Ralph,” her first produced feature film, Lee helped add dimension to 8-bit video game characters and logic to an arcade-hopping story. Franco also has a supporting role in the film, which stars Emma Roberts, Jack Kilmer and Nat Wolff as wayward teens navigating the liminal stage between childhood and adulthood in suburban Palo Alto, Franco's hometown. Coppola met Franco through mutual friends after graduating from Bard College, She had also directed a number of music and fashion videos, and after discussing mutual creative pursuits with Franco, he sent her an advance copy of his book. "I felt like the book really resonated with that emotion of being a young person and trying to find your place — of being too old for kid stuff but also too young for adult stuff," Coppola said. IOf working with Franco, Coppola said, "He was there to be helpful and supportive as much as possible, but also gave me the free range to have my own interpretation. … And he's a wonderful actor, so I really learned a lot from that perspective, and he helped me block a scene or two and gave his input because he's also a director." Coppola, who turns 27 on New Year's Day, added that she's grateful to have her family's support, even if she tried not to need it. "I'm such a fan of what they make and I'm so fortunate I have such talented people that I can turn to for advice," she said. "But at the same time, I wanted to feel like I could do this on my own and have my own voice in this." — Oliver Gettell |

|

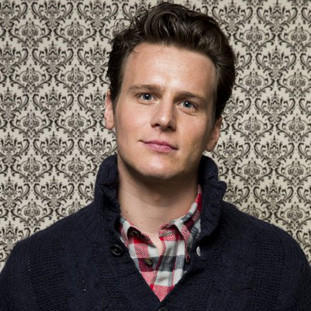

Jonathan Groff | Actor

He closed out last year as the voice of the rugged mountain man romantic lead in Disney's animated feature "Frozen." But things are about to get less PG for Jonathan Groff. The 28-year-old actor is switching out the unadulterated fun for adult-only fun when he stars in the HBO series "Looking." The half-hour dramedy, from Michael Lannan and Andrew Haigh ("Weekend"), centers on three gay friends navigating adulthood in progressive San Francisco. "It's as extreme as it gets," Groff acknowledged during a cab-ride phone call. That's no stretch. Within the first minute of "Looking," Groff's character is occupied in an awkward sexual encounter amid foliage. The Pennsylvania native made a mark as the hot-to-trot, shaggy-haired lead (Melchior) in the Tony-winning Broadway musical "Spring Awakening." He'd go on to bolster his theater cachet in productions that included "Hair" and "Red." He's also built a presence offstage with sideline TV parts. In a role that made use of his musical sensibilities, Groff had an arc on Fox's "Glee" as Jesse St. James, the male lead of the rival glee club. And in 2012 he appeared in the final season of Starz's "Boss" as an adviser to Kelsey Grammer's character, Chicago Mayor Tom Kane. — Yvonne Villarreal |

|

Annet Mahendru | Actress

Annet Mahendru could teach James Bond a thing or two. In her role as Nina on FX's "The Americans," she plays a high-level KGB agent stationed at the Soviet Embassy in Washington. She's also the lover of CIA agent Stan Beeman, who has recruited her to be his informant. But Beeman doesn't realize that Nina, newly committed to her country after discovering that Beeman has lied to her, is misleading him. The actress, who speaks Russian and five other languages, brings an exotic flavor to the drama: She was born to an East Indian father and a Russian mother and has lived in Afghanistan, Russia and Europe. Although she doesn't get much opportunity to display it on "The Americans," she has a comedy background, studying improvisation at the Groundlings School. Her other credits include "2 Broke Girls," "Mike & Molly," and "The Blacklist." — Greg Braxton |

|

Nancy Dubuc | President and CEO of A&E Networks

Nancy Dubuc has been a rising star in TV programming for more than five years. She has one of the most eclectic portfolios in television, overseeing the A&E channel, History, Lifetime and the Lifetime Movie Network. Dubuc has significantly bolstered her channel's brands by expanding the definition of what constitutes historical and A&E programming. The strategic pivot helped introduce "Pawn Stars," "American Pickers," "Hatfields & McCoys," and "The Bible" to History and "Duck Dynasty," "Storage Wars" and "Bates Motel" to A&E. She and her team have been successful in helping revive the TV movie genre for basic cable with such movies and miniseries as "Bonnie & Clyde," "Drew Peterson: Untouchable" and "Prosecuting Casey Anthony." Dubuc's challenge is to continue her streak of finding offbeat entertainment nuggets and characters (Think Robertson family of "Duck Dynasty") that go against the established grain to create pop culture. And of course, she must manage that talent (Think Robertson family of "Duck Dynasty"). Her track record is the envy of many TV programmers, undoubtedly placing her near the top of any executive wish list — although A&E Networks would not want to let her go. — Meg James |

|

John Mulaney | Actor-comedian

At 31, John Mulaney is already a seasoned TV comedy vet, with five years as a writer on "Saturday Night Live," the Comedy Central special "New in Town" and multiple late-night appearances under his belt. But in 2014 the Chicago native will take a giant leap forward with his own sitcom, "Mulaney," on Fox. In the grand tradition of comedians making the transition to series television, he'll star as a fictionalized version of himself. The show, executive produced by Lorne Michaels, will also include scenes of Mulaney's stand-up act, which with its accessible, observational style has invited comparisons to Jerry Seinfeld's. After graduating from Georgetown, Mulaney earned a name for himself in New York's downtown comedy scene with "The Oh, Hello Show," in which he and fellow Hoya Nick Kroll played fiftysomething Upper West Side divorcees with a shared love for Alan Alda. In 2008 Mulaney landed a writing job at "SNL," where he and Bill Hader created one of the show's most popular characters, night-life expert Stefon. "'SNL' was great because you rewrite so much. Going through the week you change things all the time, and you cut things you really love" he says. "A sitcom is longer than an 'SNL' sketch but only 21 minutes long. You have to be brutal." And though it may not have Alan Alda, it does have old-school appeal in the form of Elliott Gould, who plays Mulaney's neighbor, and Martin Short as his boss, a veteran comedian-turned-game show host. "He's the funniest person in the world," says Mulaney. "SNL's" Nasim Pedrad also costars. Originally developed at NBC, the series is the latest Fox sitcom, following "Brooklyn Nine-Nine," with strong ties to the long-running sketch comedy show. The multiple-camera comedy will be taped before a live studio audience, a style that has somewhat fallen out of fashion in TV comedy but one that Mulaney, given his experience on "SNL" and love for classic '80s sitcoms such as "The Golden Girls" and "Family Ties," feels strongly about. Having to do it all in one night, he says, is helpful: "There's a certain point where it's done." — Meredith Blake |

|

Kelela | Singer-songwriter

With its spacey textures and shape-shifting grooves, Beyoncé's self-titled album — released this month on iTunes with no warning — felt like the superstar end point to a year rich in adventurous R&B. Among the underground acts that appear to have inspired her is Kelela, an L.A.-based singer-songwriter known for layering smoldering vocals over starkly futuristic beats. Raised in Maryland by parents who'd emigrated from Ethiopia, the 30-year-old put out a free Internet mixtape in October called "Cut 4 Me." It attracted instant attention from hipsters and tastemakers with tracks like the clanging "Enemy" and "Cherry Coffee," a woozy ballad lined with lonely sounding sonar pings. Beyoncé wasn't the only member of the Knowles family listening. In November, the star's sister Solange included Kelela's song "Go All Night" on an acclaimed avant-soul compilation alongside tunes by other up-and-comers such as Jhené Aiko and BC Kingdom. "I think it's really awesome to hear someone who's doing something so incredibly experimental but that still really, really values the art of the vocal," Solange told Billboard. Now, Kelela is at work on her first studio disc, reportedly with help from Hudson Mohawke, a Scottish producer with close ties to Kanye West. Expect something that soothes even as it unsettles. — Mikael Wood |

|

Travi$ Scott | Rapper-producer

Travi$ Scott is a 21-year-old L.A.-via-Houston rapper and producer, one so versatile and provocative that he makes having a dollar sign in his rap alias seem original. His eerily beautiful sonics and fevered delivery have earned him co-signs on two rap-titan major label imprints: Kanye West's G.O.O.D. Music and T.I.'s Grand Hustle. Behind the mixing boards, he helmed tracks for Ye, Jay Z and John Legend on their respective agenda-setting albums in 2013. Now after his debut EP, "Owl Pharaoh," in May, he's ready to take center stage himself. For the clearest look at his vision, check out the seven-minute surrealist, ghastly video for "Upper Echelon" — you'll wonder whether his next move could be directing an episode of "American Horror Story." — August Brown |

|

Zara McFarlane | Singer-songwriter

One of the real pleasures of 2013 has been the many fresh faces on the jazz vocal front, including José James, Gregory Porter and young phenom Cécile McLorin Salvant. Deserving of mention amid this rising tide of unique talent is London-born Zara McFarlane, who next month releases her second album, "If You Knew Her," on tastemaker Gilles Peterson's label. Her standing as a promising star in Europe is only confirmed with recent stints sharing the stage with Porter and Dianne Reeves, and she has already earned airplay on KCRW-FM (89.9) for a lush and arresting recast of the late Junior Murvin's reggae classic "Police and Thieves." Echoes of vintage soul and Britain's so-called acid jazz scene from the '90s echo through various points of McFarlane's album, but some of her greatest promise can be heard on the new record's elastically swung single "Angie La La," a buried treasure from reggae vocalist Nora Dean that features trumpeter-vocalist Leron Thomas with McFarlane's nimble band. But ultimately, it's about songwriter McFarlane's talent and voice here. Echoes of Nina Simone and Ella Fitzgerald shimmer at the margins, along with the sound of a rising talent claiming new ground of her own. — Chris Barton |

|

Sam Smith | Singer-songwriter

Last fall, singer Sam Smith was working as a bartender in London. Today, his picture hangs alongside Katy Perry's inside the Capitol Records building just off Hollywood Boulevard. The 21-year-old's trajectory from mixologist to pop star is largely because of the U.K. band Disclosure's 2013 dance hit "Latch." The song, omnipresent in the U.K., is anchored by Smith's scorching vocals. "The minute 'Latch' happened, everything has been 100 mph," Smith said on a recent trip to Hollywood. "Everyone who sees me thinks this has happened very quickly. But it's been quite a long slog." Smith, who began singing when he was 8, trained with a jazz vocalist before studying musical theater. Yet he found notoriety in the pop world via a dance tune and after posting his song "Lay Me Down" on YouTube. It's garnered more than 1.5 million views since January. Smith recently signed to Capitol in the U.S., and his debut album, "In the Lonely Hour," is set for summer release. Though the initial hits that brought Smith into the limelight are aimed at the dance floor, his solo work leans toward ballads filled with yearning, heartache and minimalist grooves. "It's soul music, but I give it to you in different ways. Sometimes it's an electronic sound, sometimes it's completely stripped back," he said. During a recent stint at the Troubadour in West Hollywood, he previewed the stark missive "Leave Your Lover." But it was the more familiar "Lay Me Down" that really struck a chord. Couples embraced, the glow of smartphones lighted up the room and a few concertgoers even shed tears. "These songs are so personal," said Smith, running his hand through his coiffed hair. "I'm always so shocked when people know who I am. It's very strange." — Gerrick D. Kennedy |

|

Philippe Jaroussky | Countertenor

Countertenors are a decidedly acquired taste — men who are trained to sing in the manner of women, or more accurately, in the style of the castrati, those singers hundreds of years ago who were castrated at a young age to preserve their boyish voices. In this rarefied (even for opera) domain, French singer Philippe Jaroussky stands as the hottest young thing. Charismatic, dashing and still youthful at 35, he has entranced European audiences with his otherworldly pitch and vocal dexterity, while also amassing a sizable online following. The concert will mark just the second time Jaroussky has performed in Los Angeles, the first being a 2011 concert at Royce Hall with the Baroque ensemble Apollo's Fire. Speaking recently by phone from Paris, Jaroussky discussed his career and his fascination with Farinelli, the celebrated 18th century castrato, who collaborated closely with Porpora. Here are excerpts from the conversation, which was conducted in French. — David Ng |

|

Khatia Buniatishvili | Pianist

The sultry young Georgian pianist Khatia Buniatishvili sneaked into Los Angeles under the radar last February for an underpublicized recital debut at Cal State L.A.'s Luckman Theatre. But her Los Angeles Philharmonic debut in January will not be so stealthy. Buniatishvili will be playing Chopin's Second Piano Concerto with another young Eastern European — Polish conductor and Indianapolis Symphony Music Director Krzysztof Urbanski, who made an impressive Hollywood Bowl debut last year. Conveniently found on YouTube rhapsodically carried away in the likes of Liszt and Rachmaninoff, wearing the reddest lipstick and conveying cinematic emotions, Buniatishvili may seem the ideal Hollywood pianist, the kind sultry actresses pretend to be when they portray classical pianists. What they can't so easily reproduce, however, is Buniatishvili's electrifying elegance. Two of her greatest champions happen to be two of today's greatest musicians with exactly that same combination of passion and commitment — pianist Martha Argerich and violinist Gidon Kremer. — Mark Swed |

|

Profeti della Quinta | Vocal group

Galilee may seem a strange place to put together a male vocal group that specializes in Italian Renaissance music, but the Israeli early music specialists known as Profeti della Quinta — now based in Switzerland — has particular reason to make a specialty of a late 16th and early 17th Mantuan composer. Salomone Rossi was a Jewish violinist in Monteverdi's orchestra who invented the trio sonata and who became the first composer not only to write new music for Jewish religious services but to controversially introduce the polyphonic music into the synagogue. Rossi is the subject of Profeti's gorgeous new recording on Linn, "Il Mantovano Hebreo" and of a new Rossi documentary with the same title. On Jan. 30, Profeti will bring a rare Rossi program that includes a screening of the film to the newly renovated Wilshire Boulevard Temple on Wilshire, offered as part of the Da Camera Society's Chamber Music in Historic Sites series. — Mark Swed |

|

Sunny Yang | Cellist

The Kronos Quartet's new cellist, Sunny Yang, has what might seem the hardest job in all string quartetdom. A recent USC grad born in Korea a dozen years after the famous new music foursome was formed, Yang joined Kronos in June just in time for the quartet's 40th-anniversary celebrations. Were she expected to master the full Kronos repertory, that would include more than 800 works the ensemble has commissioned. But Yang gets a break given that Kronos always has a large number of new quartet irons in the fire, which means all the players are learning new music all the time. Plus she has already proved a cool cucumber for whom no challenge seems too great, as evidenced by her appearances this fall in the U.S. premiere of Philip Glass' complex and difficult Sixth String Quartet in Las Vegas and at a 40th birthday concert in Berkeley in which a theatrical performance of George Crumb's "Black Angels" (the first piece Kronos ever played) ended the program with profound and darkly ecstatic poetry. Cool, yes, but she also cooked in Vegas with the old Kronos favorite, a once-shocking string quartet arrangement of Jimi Hendrix's "Purple Haze," and in Berkeley when the National guitarist Bryce Dessner joined Kronos for his recent piece, "Aheym." Yang's first Los Angeles appearance with Kronos will bring her almost back to her Southland roots, not USC but — block that kick — UCLA for two programs in Royce Hall that include "Black Angels" on March 14 and an evening-long new work by Laurie Anderson, "Landfall," March 15. — Mark Swed |

|

Yotam Haber | Composer

Young composers, righteously impatient over intolerance, are unleashing large forces to combat injustice. First there was Mohammed Fairuz's "Poems and Prayers," a symphony for hundreds of instrumentalists and singers that tackles the Palestinian and Israeli morass through persuasive music and poetry at UCLA this month. Next, the week of Martin Luther King Day at REDCAT and courtesy of CalArts comes Yotam Haber's "A More Convenient Season." A commission from the University of Alabama to commemorate the 50th anniversary of a Ku Klux Klan church bombing in Birmingham, Ala., that killed four black children, this opera/oratorio for orchestra, chorus, vocal soloists, electronics and film takes its title from a letter King wrote from jail in which he famously declared "that justice too long delayed is justice denied." Haber, 36, was born in Holland and grew up in Israel, Nigeria and Milwaukee. His music is similarly wide-ranging, taking inspiration from Minimalism, Modernism and world musical traditions. He serves as artistic director of MATA, a New York organization Philip Glass helped found to support young composers. The composer calls "A More Convenient Season" not multimedia but multi-spectral. It envelops the audience with the sights and sounds of Birmingham in the '60s, the horror of the era but also it the strains of hallelujah that led to profound lasting change. — Mark Swed |

|

Taraji P. Henson | Actress

She may not be a household name, but Taraji P. Henson has notched quite a few milestones in her young career. Nominated for both an Oscar ("The Curious Case of Benjamin Button") and an Emmy (Lifetime's "Taken From Me"), Henson has garnered attention for her portrayal of detective Joss Carter on the CBS crime drama "Person of Interest." Not only has she held her own in a film starring Brad Pitt but she even has a blockbuster on her acting resume: "Think Like a Man," which did so well during its opening weekend that it spawned an upcoming sequel. All of which is to say she's ready for her theatrical close-up. Henson stars in the world premiere of New-York-Times-reporter-turned-playwright Bernard Weinraub's "Above the Fold," which opens at the Pasadena Playhouse on Feb. 2. Henson plays an enterprising African American New York journalist called on to investigate a racially sensitive story at a Southern university. Professional ethics are challenged by the new pressures of digital journalism and the old pressures of objectivity. No doubt that familiar character flaw that Macbeth called "vaulting ambition" will come into play as well. A topical tale (recalling the 2006 Duke lacrosse case), "Above the Fold" showcases a talent on the verge of making headlines. — Charles McNulty |

|

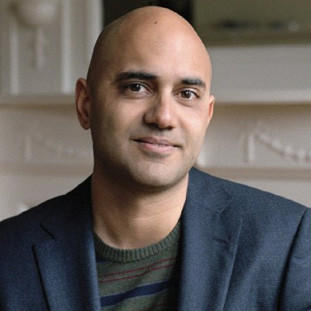

Ayad Akhtar | Writer

"At first I thought it was a crank call," Ayad Akhtar told the British newspaper the Telegraph about the announcement that his play "Disgraced" won the 2013 Pulitzer Prize for drama. This isn't false modesty. Although "Disgraced" was well received when it was produced by Lincoln Center Theatre after a successful world premiere at Chicago's American Theater Company, Akhtar, a 43-year-old New York-born writer of Pakistani heritage, hadn't exactly established himself as a force to be reckoned with in the American theater. A novelist, screenwriter and occasional actor, Akhtar (who co-wrote and appeared in the film "The War Within") hurtled to the front ranks of American playwriting with this drama that practically exploded during a dinner party scene when the subject of Islam is introduced among a group of successful New York strivers. His latest play, "The Who & the What," has its world premiere at the La Jolla Playhouse in February. It too explores the tinderbox of religion, this time by exploring the conflict that spirals out of control within a conservative Muslim family in Atlanta when an independent-minded daughter writes a book on women and Islam that offends her more traditional father and sister. Akhtar's approach? Ferocious comedy. Add bravery to the list of qualities of a writer we'll soon become better acquainted with. — Charles McNulty |

|

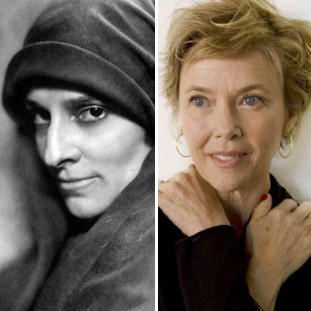

Ruth Draper and Annette Bening | Actresses

Annette Bening, right, is a face accustomed to being watched, but this year she'll be lending her famous visage (and veteran theatrical craft) to the work of a solo performer who ought to be better known given the scale of her influence: Ruth Draper. Bening is performing a bill of Draper monologues at the Geffen Playhouse beginning in April. Teaming with telling detail and shot through with satire, these richly dramatic character sketches have a novelistic amplitude. Perhaps that's the reason Henry James was so taken with the young Ruth Draper, whom he encouraged with words of Jamesian enchantment: "You have woven yourself a magic carpet — stand on it!" Draper was equally heralded by actors. John Gielgud considered her, along with Martha Graham, to be "the greatest individual performer that America has ever given us." Uta Hagen said each of her characterizations was like "a Rembrandt on stage." And Lily Tomlin confided that when she discovered Draper's recordings she had found "a standard," "something to aspire to." Theater critic Kenneth Tynan may have said it best, however, when he wrote in a 1952 review that Draper "has all but ruined the pleasures of normal play-going, since her large supporting cast, which exists only at her mind's fingertips, is so much more satisfactory than any which makes the vulgar mistake of being visible." Taking inspiration from Ruth Draper's art, Bening, a singular yet slyly flexible performer, gets the opportunity to demonstrate just how multifarious she can be. — Charles McNulty |

|

Josie Walsh; Melissa Barak | Artistic director-choreographer; artistic director-choreography-dancer

There's an undeniable synchronicity to the career arcs of Los Angeles natives Josie Walsh, left, and Melissa Barak. They are alumnae of Westside Ballet; both became ballerinas with prominent national companies — Walsh with Joffrey Ballet and Barak with New York City Ballet. Then in 2010, Walsh got a commission from Los Angeles Ballet and cast Barak (then a soloist with LAB) in a leading part. Now, these outspoken women are forging against the local head winds and heading up their own contemporary troupes, Walsh's Ballet Red and Barak's Barak Ballet. The award-winning Barak has a sophisticated and complex style that is nonetheless warm and human. She exhibits a keen intuition of how movement affects an audience. Each woman is planning (separate) concerts in June at the Broad Stage. "If I can find that raw, visceral internal dialogue through totally contemporary movement and fuse it through the ballet syllabus, that has been my path," Walsh said. In addition to creating new work for her own company, Barak has commissions from Sacramento Ballet and Richmond Ballet in 2014. And she has found an interim executive director, Christopher Clinton Conway, a onetime Joffrey Ballet administrator. Said Barak: "I want nothing more than to give L.A. its own unique ballet company." — Laura Bleiberg |

|

Nikolai Tsiskaridze | Dancer

Nikolai Tsiskaridze began the 21st century as arguably the greatest Russian danseur of his generation: a 6-foot-1, perfectly proportioned, brilliantly trained star of the Bolshoi Ballet as well as someone who would quickly become a respected ballet coach and a popular television celebrity. But eclipsing those excellences in the next decade was his role as the Edward Snowden of Russian dance. At great personal risk, Tsiskaridze refused to be silent about the corruption he found at the Bolshoi in the treatment of the dancers and the remodeling of the theater, to name a few. His unrelenting accusations led to his dismissal from the company. Some of them involved the crime that had everyone in the ballet world talking and texting for almost a year. On Jan. 17, the Bolshoi's artistic director was nearly blinded by an acid-throwing assailant — a scandal that exposed just how venomous the conflicts in the company had become. Tsiskaridze testified for the prosecution at the recently concluded trial of the accused perpetrators. But he stayed in the news for more reasons than his testimony. Suddenly, he was appointed the head ("acting rector") of what is widely regarded as the greatest ballet school in the world: the Vaganova Academy in Saint Petersburg, affiliated with the Mariinsky Ballet (formerly the Kirov). Tsiskaridze is much loved as a guest artist with the Mariinsky, and that company has given him roles that were denied him at the Bolshoi. But the bedrock differences in style between the companies has made his new position controversial in the extreme, so you can bet he'll remain in the news — as reliably dramatic in his speech as he always was in his dancing. — Lewis Segal |

|

August Bournonville | Choreographer

August Bournonville died in 1879, but memories of this great Danish ballet choreographer are likely to be alive and well in May and June when Los Angeles Ballet presents his two-act masterwork "La Sylphide" in four theaters throughout Southern California. Bournonville's classical style is not as bold or space-devouring as Russian classicism, but it emphasizes intricacy and effervescence, qualities hard to master by dancers trained in other techniques. In the distant past, Los Angeles audiences saw a stylistically clueless "La Sylphide" by American Ballet Theatre and a hopelessly crude production by the Bolshoi Ballet. But Los Angeles Ballet's performances in 2009 were exemplary, among the finest achievements in this company's history. The late spring staging will again be by Thordal Christensen, Los Angeles Ballet artistic director and a former artistic director (1999-2002) of the Royal Danish Ballet, Bournonville's home company. Based on a French original, the work itself is a high-Romantic dance drama from 1836 about a young Scot who has everything he needs, including a girl who loves him. But even on his wedding day, he dreams of something more: an ideal love from a parallel universe. And when that dream girl flies in at his window, demanding that he leave his old life behind, the results are momentous for everyone. — Lewis Segal |

|

Anne Ellegood | Curator

Hammer Museum Senior Curator Anne Ellegood will likely see some attention this spring with the debut of her long-mulled, provocative show "Take It or Leave It: Institution, Image, Ideology." The 35-artist historical show — co-organized by Ellegood's friend, New York-based art historian Johanna Burton — is an institutional critique of museums themselves as it examines American artists who the curators felt have changed the way we, as a culture, think about art. Among those included in the exhibition, focusing on work largely from the '80s and '90s, are Barbara Kruger, Mike Kelley, Jimmie Durham, Adrian Piper and David Wojnarowicz. "It's kind of a risky show," Ellegood says. "It's a historical show that, woven into the curatorial approach, is also a question about historical shows themselves." Ellegood says it's important to note that the show strives to be educational and sprightly challenging, not aggressively or aimlessly critical. "The artists who are evaluating the institution are critiquing it not because they want to burn it down but because they love the institution and want it to be a better place — to be more inclusive, to grapple with the most difficult issues of the day, to be a space for dialogue," she says. Originally from Portland, Ore., Ellegood, 46, spent seven years honing the idea for "Take It or Leave It," which she says grew out of casual conversations with Burton (who's now at New York's New Museum of Contemporary Art, which isn't affiliated with the show). Throughout Ellegood's four years as curator of contemporary art at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., as well as her time as an associate curator at the New Museum, she couldn't let the idea go. It wasn't until Ellegood came to the Hammer in 2009, however, that she brought the show to life. "In a way, it's the show I'm most proud of," she says. — Deborah Vankin |

|

Phillip K. Smith III | Artist

Phillip K. Smith III's light installation "Lucid Stead" — a worn, wooden homestead shack tricked out with mirrored slats and multicolored LED lights — stood alone in a dusty desert clearing just outside Joshua Tree for two weekends in mid-October. Only 400 or so people visited the structure in person as it shimmered in the high noon sunlight and glowed red, orange and pink at sunset. The shack became something of an Internet sensation, with the video garnering more than 300,000 views on lucidstead.com and catapulting the artist into a whole new stratosphere of recognition. Smith, 41, grew up in the Palm Springs area and spent 11 years on the East Coast after earning dual degrees in fine arts and architecture from the Rhode Island School of Design. He returned to Palm Desert in 2000, where he lives now, because "When you grow up in the desert, it's in your blood," he says. Throughout his career, Smith has created more than a dozen large-scale sculptures across the country, including an over-50-foot fiberglass piece, "Inhale/Exhale," for the University of La Verne in 2009 as well as publicly and privately commissioned sculptures in Kansas City, Mo., Nashville, Arlington, Va., and Scottsdale, Ariz., among other places. While he was the 2010 artist in residence at the Palm Springs Art Museum, Smith created a 24-foot-long acrylic sculpture backlighted by LED lights that served as the inspiration for "Lucid Stead." "Lucid Stead" is no longer up, but Smith's smaller-scale works can be seen in the show "Lightworks," now on view at Palm Desert's Royale Projects. The artist also will have a solo show next month at the Museum of Art and History in Lancaster. "Lucid Stead: Four Windows and a Doorway" opens Jan. 18 and will feature five works made of physical elements, taken out of context, from "Lucid Stead"; together, they constitute a new, single installation. — Deborah Vankin |

|

Gabriel Kuri | Artist

Gabriel Kuri is already a significant midcareer contemporary Mexican artist — he's had solo museum and gallery exhibitions around the world and been part of the 2003 and 2011 Venice Biennales as well as the 2008 Berlin Biennale. In the late '80s and early '90s he was part of a collective that studied at Gabriel Orozco's Mexico City studio. The group — which included Damián Ortega, Abraham Cruzvillegas and Dr. Lakra — regularly showed its work at the Mexico City gallery Kurimanzutto, co-owned by Kuri's brother José. After 10 years of living and working as an artist in Brussels, the 43-year-old Kuri moved his family to Los Angeles in August, for personal and professional reasons."It was great to be in Belgium, but we didn't want to wake up there and find it impossible to leave because we'd dug roots," he says. "Here in L.A. I'm close enough to Mexico, but I have my own space. Also, the arts are exciting here," he adds. "It's a scene of artists, not a scene that's about the market." Kuri studied art at Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas in Mexico City before pursuing a master's at Goldsmiths College of Art in London. His work explores consumer culture and how we repurpose the material world, both natural and artificial, via sculptures and collages created with found objects and the detritus of his everyday life — shopping receipts, ticket stubs, stray plastic bags, leftover hotel shampoo bottles as well as natural elements he finds outdoors, like marble and stones. His work is on view at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth as part of the exhibition "Mexico Inside Out: Themes in Art Since 1990" (through Jan. 5). Kuri's solo exhibition "bottled water branded water" is on view at Parc Saint Léger in France through Feb. 9. In May, Kuri's first L.A. solo exhibition will open at Regen Projects. He can't yet say what exactly will be included in the show — just that he aims to make it different from anything he's done before. "I want it to be in the classic Gabriel Kuri tradition, for people not familiar with my work, and also it's quite important for me to reinvent myself," he says. "Restarting is extremely important for artists. This exhibition has to be at a zero starting point, with a reminder of where I was." — Deborah Vankin |

|

Edan Lepucki | Novelist

Edan Lepucki's first novel, "California," due out in July, comes steeped in Southern California narrative tradition: "a post-apocalyptic domestic drama" (or so she calls it) about a couple that escapes a devastated Los Angeles to raise a child in a new and elemental world. One thinks of Steve Erickson or Cynthia Kadohata, or Carolyn See, whose 1987 novel "Golden Days" ends with the nuclear holocaust. "I wanted to write about the future," the 32-year-old author says by email, "but have the personal relationships be [the] central concern." Then, one evening, she was driving along Sunset Boulevard, and at the boundary between Echo Park and Silver Lake, the streetlights had gone out. "I wondered," Lepucki remembered, "what it would be like to live in a ruined L.A. — no services, the roads neglected — and I extrapolated from there." For Lepucki, there's a strong personal connection at work here; although she currently lives in the Bay Area, she's an Angeleno born and raised. A staff writer for literary web site the Millions, she "write[s] about books as a way to understand what I've read," and she runs a writing school, Writing Workshops Los Angeles. "For me," she says, "a literary life involves books, sentence-making and rich conversations with other writers and readers. (Also: coffee and chocolate)." Lepucki's novella, "If You're Not Yet Like Me," appeared in 2010 from the independent press Flatmancrooked, but as a first novel, "California" represents a different order of debut. "Once you start a novel," she says, "everything gets folded in: pregnancy, parenthood, my experiences as a student at Oberlin College … sibling relationships, suicide bombers, gated communities, coyotes, baking. … How it became a book? Sheesh … I have no clue." — David L. Ulin |

|

Cristina Henríquez | Novelist

Cristina Henríquez likes to quip that her forthcoming novel, "The Book of Unknown Americans," is "the great Delaware novel everyone's been waiting for." The daughter of Panamanian immigrants, Henríquez grew up in Newark, Del., a suburb of Wilmington, but now lives in Chicago. Her novel, to be published in spring by Knopf, tells the story of Latin American families whose journeys to the U.S. bring them to the same apartment building in Delaware. It's a sweeping and ambitious work, with the point of view shifting among a dozen different characters: Mexican, Guatemalan, Nicaraguan. "I have a lot of people ask me why it's set in Delaware," Henríquez, a 36-year-old graduate of the Iowa Writers Workshop, said in a phone interview. "My answer is that there are communities like this everywhere." Henríquez set her first two books (the story collection "Come Together, Fall Apart" and the novel "The World in Half") in Panama, a country she visited often as a child. But in her lifetime, a kind of Latino country has been spreading across the United States: from places like Gettysburg, Pa., and Grand Island, Neb. Her new novel is an attempt to describe the nation we're becoming. "The Book of Unknown Americans" has a love story and an accident at its center. Much of the action unfolds on a street like Newark's Kirkwood Highway. "My mom is a translator for the school district in Delaware," Henríquez says. "She'd hear these different stories from working with families there. Those stories stuck with me." — Hector Tobar |

|

'Welcome to Night Vale' | Storytellers

Twice monthly, an eerily calm voice reports the news from Night Vale. Like other small towns, Night Vale has PTA meetings, local construction projects and a high school football team. However, most small towns aren't haunted by a glowing cloud, their stray dogs don't have three heads and passing sandstorms don't create replicants. "Welcome to Night Vale" is a podcast created by Joseph Fink and Jeffrey Cranor that's a mash-up of H.P. Lovecraft and "Prairie Home Companion." The show reached the top of iTunes' podcast chart in late 2013, which led to a book deal: A "Welcome to Night Vale" novel will be published by HarperPerennial in 2015. Fink, 27, is from Camarillo; Cranor, 38, grew up in Texas and Oklahoma. The two met doing experimental theater in New York, but set "Night Vale" in a remote desert where the boundary between real and unreal stretches thin. "Welcome to Night Vale" is the best fictional podcast out there, a terrific example of how the form can be used for storytelling. Like quality science fiction, it's a world with impeccable continuity that's able to grow in unexpected ways. And like Charles Dickens, Fink and Cranor write serially, often responding to the ideas of their listeners. The show's creators maintain a close relationship with their fans, answering emails and doing a live stage version (a 2014 West Coast tour is almost sold out; there are still tickets for the late show at Largo at the Coronet on Jan. 25). Cranor and Fink understand that in the new media landscape, a writer's job isn't just to write: It's to bring stories to audiences wherever they are.

— Carolyn Kellogg |

|

Ruben Farrus | Game Designer

A game designer today at independent studio Minority Media, Ruben Farrus remembers the nightmares he had as a teenager. He can't forget because he continues to have them. They're a holdover from being bullied. "Every couple weeks I see my bullies in front of me," Farrus says. "I try to push them back. I try to hit them. But I cannot. I cannot throw a punch. I am motionless. I am powerless." As a kid he played a lot of games. He also read a lot of books. Looking back today at that time, Farrus, now 30, feels the books provided him with "tools for life." The games? Not so much. "When you're a kid," he says, "you're naturally attracted to games. They look fun, so it would be perfect if you could get something out of it." That's the goal shared by Farrus and the Montreal-based Minority Media. Farrus contributed to Minority's 2012 title "Papo y Yo," which used dreamy landscapes and a frog-chomping monster to metaphorically deal with topics of paternal abuse. In early 2014, Minority will release "Silent Enemy" for mobile devices, a Farrus-designed game that will address bullying. Like "Papo y Yo," it will do so in a fairy tale-like universe. "In "Silent Enemy" a boy gets lost in a sub-arctic region, where he'll require the help of friendly animals to locate warmer climates. Crow-like creatures will intercept him on his journey. They will be "all powerful, all evil," says Farrus, but they won't be typical video game villains." — Todd Martens |

|

Ryan and Amy Green | Game Designers

The setting is a hospital. A father is exasperated, a child is crying and it's your job to find out why. But any victories will be small, as "That Dragon, Cancer" explores the ups, the downs, the everyday terror, the sudden miracles and the dreaded inevitability of caring for a loved one with terminal brain cancer. So … wanna play? Ryan Green, his writer-wife, Amy, and a small team near Fort Collins, Colo., are in the early to middevelopment stages of "That Dragon, Cancer," a narrative-driven game they hope to complete and release by the end of 2014 for the home video game console the Ouya. Its tale is a personal one, initially conceived by Ryan and Amy in part as a way to help them and others express and cope with the unthinkable. At around 12 months old, their son, Joel, was diagnosed with terminal cancer and was given about a month to live. He's now 4, and the Greens are posting updates of his treatments online (Joel was undergoing radiation sessions in mid-December). Ryan, 33, who dreamed of someday being a filmmaker and has worked in mobile game development, ultimately determined the interactive medium was the one best suited for handling such a serious topic. While the area explored by "That Dragon, Cancer" may seem more suited for an indie film, he believes that by offering players a choice they can better experience "the themes that we have faced." "Video games are the perfect nexus of all these different mediums," Ryan says. "It takes everything I love about film and animation, and it adds the nuance of immersion. You're asking a player to do something and then they evaluate it as if they are doing it." It's not, Ryan stresses, a game designed to make players miserable. Parts will no doubt be difficult for some players to stomach, but he wants the game to start a conversation. Early scenes show the stress and weariness of a parent who has spent a late night in the hospital, and later Ryan wants to show players the perspective of the medical staff. The end of the game has yet to be scripted, but he envisions it more as a series of vignettes. "Ninety-eight out of 100 people are going to have somebody that they knew with cancer," he says. "Everyone can identify with the pain that causes, but I also hope I can give you the same comfort I have received." — Todd Martens |

|

ISSA RAE | ACTRESS-WRITER-DIRECTOR

The 28-year-old actress and writer first attracted notice with "The Misadventures of Awkward Black Girl," a Web series that follows the title character, J, through comically uncomfortable situations on the job and in her personal life (including one moment in which a white co-worker at a call center attempts to touch her hair). Rae's sharp writing attracted the notice of Pharrell Williams, who featured the series on his I Am Other YouTube channel, and also of "Scandal" creator Shonda Rhimes, who worked with her on a pilot called "I Hate L.A. Dudes" that ABC decided not to pick up. She's joined with "The Bernie Mac Show" creator Larry Wilmore to write a pilot for HBO. She created, wrote and sometimes directed the Web series "The Choir," a comedy set in the United Church of Holy Christ in Fellowship's choir as the members attempt to rebuild their dying congregation through innovative and sometimes inappropriate ways. When not in front of camera, Rae is writing a book of personal essays. — Dawn Chmielewski |

|

MIKE HOPKINS | HULU CHIEF EXECUTIVE

Hulu, the popular online TV service known for its sleek design and free access to current TV episodes, has won raves from consumers who've flocked to the site since it launched in 2007. Users credited the company's first chief executive, Jason Kilar, for building a service that could revolutionize TV. But momentum stalled as its media company owners — 21st Century Fox and Walt Disney Co. — were divided over how best to position the service. Now Hulu is at a crossroads, and it's up to Hopkins to navigate the thicket of problems that Hulu created for cable TV companies and Hulu's owners. Hopkins also must figure out how to keep Hulu relevant as more aggressive digital services, Netflix and Amazon.com, spend lavishly to bolster their exclusive content. Hulu is poised to remain a significant player in digital media as more people migrate to streaming services. The Santa Monica company's revenue nearly doubled in 2013 to $1 billion, and new advertisers have jumped on board. Observers are watching to see whether Hopkins will reposition the service. Some expect Hulu to become an offering from cable and satellite TV companies trying to retain subscribers who want to watch TV on their laptops, tablets and smartphones — not just the big screen at home. Hopkins, who has an MBA From UCLA's Anderson School of Management, spent more than 15 years at Fox, where he helped launch new cable channels and wrangle programming agreements with cable companies. — Meg James |

|

Nancy Tellem | Microsoft's president of entertainment and digital media

The veteran CBS television executive had her work cut out when she joined Microsoft Corp. in 2012 to launch a Santa Monica studio to create original content. Long fascinated with changes in consumer behavior, Tellem is now playing an important role in determining what appeals to younger consumers accustomed to getting their entertainment on multiple screens. She is trying to build on the momentum that Microsoft has achieved by encouraging millions of consumers to consider the Xbox more than just a video game console. Xbox users spend more than half of their time online listening to music and streaming movies, TV shows and exploring other entertainment options. Microsoft wants to build a trove of exclusive content to differentiate its game system from the rival Sony PlayStation. Microsoft's slate of new shows designed to appeal to the digitally connected generation is expected to launch in the first half of 2014. Microsoft also brought Tellem on board to make inroads with Hollywood's creative community. One of the first projects she announced was a live-action TV series, produced by Steven Spielberg, based on the "Halo" game franchise for Xbox Live, a feature that enables gamers to play against online opponents. Tellem was trained as a lawyer and worked her way up the ranks in business affairs at Lorimar, Warner Bros. and then CBS. At the broadcast network, Tellem was a key executive in the development of new shows, including the hit reality show "Survivor." She was one of the TV industry's first female entertainment presidents. — Meg James |