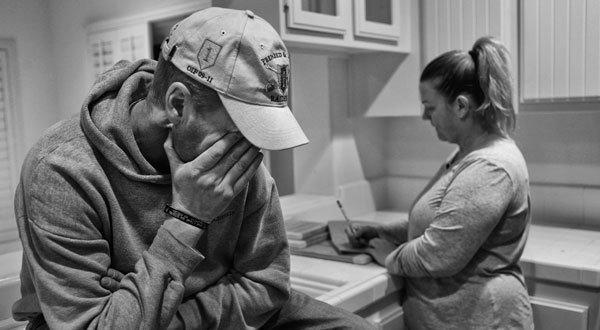

Candace Desmond-Woods tries to comfort her husband, Tom, an Iraq war veteran who suffers from PTSD and alcoholism. More photos

A SOLDIER'S WIFE

Her husband came home, and the war came with him.

September 8, 2013

O

ne night her husband thought he was back in Iraq and tried to kick down the door of their home on Garden Gate Lane. He shouted something in Arabic she didn't understand. As a cavalry scout in Baghdad, he had crashed through countless doors on nighttime raids. The "hard knock," he called it.

She clutched their infant son, afraid of her husband for the first time. She wouldn't let him in. He stared at her through the glass panes. Didn't he recognize her? He shoved, elbowed, punched. The lock began to buckle. The glass shattered.

It was February 2012. The war, her own small piece of it, had come rolling down the block the month before, in the form of a 22-foot Penske moving truck. Her newlywed husband was at the wheel, having crossed the country from Ft. Riley, Kan.

Candace Desmond-Woods told herself everything would be fine, now that he was out of the Army. Their lives as husband and wife would really begin in this white-fenced rental home in Irvine, a master-planned city where every manicured block was an argument against uncertainty.

The war would crash through her careful plans in a hundred ways, large and small. She watched it empty her refrigerator and shut off her gas. She came to feel like one of its strangest casualties, a widow with a living husband.

HIS PAINFUL RETURN

He had carried the dead with him from the start, the names engraved on the black metal bands he wore on his wrists. She had met him at a party in Newport Beach in the summer of 2009, after his first battle tour in Iraq with the 1-4 Cavalry Regiment.

Candy was 35, with blond hair, light freckles and blue-green eyes. She believed strongly in the war, and admired his willingness to put his life on the line for his country rather than just talk about it.

Tom Woods was 34, a lanky, redheaded Army sergeant and former race car driver from San Jose. Nearly 6 foot 4, he towered over her by a foot.

They fell in love over Skype and email, during his second tour. He sent emoticon hearts. He sent real-life daisies, remembering that she disliked roses. When he returned, he twirled her in the air.

She loved how gentle he was with her two daughters from her first marriage, Lizzie, 15, and Addy, 6. She felt like the epitome of the good girl — PTA, Charity League, classroom mom — and he possessed an aura of danger she found irresistible.

She would send him on a grocery run, and he would come back with a plastic display crab under his arm and a devilish glint in his eye. He would sneak her onto a private beach at night, and open the champagne bottle with his combat knife.

He loved that she was a little bit of a tomboy. "Not all prissy," he said. When he visited her at work, where she cared for children with autism and Down syndrome, he told her he was in awe of her patience.

He was unlike any man she'd known. In her world, girls didn't fall for soldiers. They didn't even meet soldiers.

When she visited him at Ft. Riley, he drove his Jeep Wrangler around the base with an open bottle of Jack Daniels in the cup holder. He took her to bars with his combat buddies — a rowdy, profane group, always ready for a brawl. It thrilled her.

She knew he drank too much, but she also knew he had experienced terrible things during his 14 months in Baghdad in 2007 and 2008. As part of the "surge," the 1-4 Cavalry patrolled bomb-laden roads and went door-to-door hunting insurgents.

She understood only a little of what he'd seen. She'd heard him speak with pride of the time Gen. David H. Petraeus, then commander of coalition forces in Iraq, shook his hand, and of how his platoon had built soccer fields and schools and helped businesses return to war-ravaged southern Baghdad.

But the other parts — the details behind the bracelets with the names of his dead friends — he didn't talk about. He told her she didn't really want to know.

She pressed him, gently. He told her about a pile of dogs, killed by his men and left on a corner — the barking had been giving away their presence on nighttime raids — and the image stayed in her mind. But he seemed to shrug it off.

She learned the most from a soldier who had fought with him. We lost a lot of friends, he said. When the blasted Humvees were towed back to base, Tom had to scrub the blood off the radios and ammo boxes.

She knew he was hurt in ways she didn't understand. She thought he deserved a chance.

They were married in the spring of 2011, when she was seven months pregnant with their son, Blake.

The wedding ring was white gold with a small diamond, scaled to a soldier's wages, purchased from an Army catalog.

"I found the perfect man," she would remember thinking, "and we'll have this great life."

Video: A Soldier's Wife

When Tom talked about life in the 1-4 Cavalry, he made it sound as if drinking was inseparable from a cavalry scout's identity. At parties, every "true cavalry scout" would dip his Stetson into the grog bowl — a plugged-up sink mixed with whatever mad combination of liquor was on hand — and swig right from the brim.

"Everybody drinks," Tom would say.

She told herself the Army was the problem, that he'd sober up once he got out.

She told herself this even after she gave birth to Blake and discovered whiskey bottles and beer in the duffel bag Tom brought to the maternity ward.

Even after she visited his Kansas apartment, looked into his refrigerator and saw whiskey, but no food.

Even after he dropped the baby, something she was prepared to attribute to his bad shoulder, and then tried to drink his guilt away while Blake was in the hospital with a concussion.

Even after she learned that Tom had been caught drunk on duty, and was being stripped of his sergeant's stripes and forced out early with a general discharge.

Once he was home in Southern California, she told herself, they would get him help. They had lived apart for the whole time they'd known each other, because he was either on base or at war, and now was their chance to live day-to-day as a family.

She'd introduce him to her lifelong friends. She'd bring him to barbecues, and to her daughters' swim meets and cheer-squad practices. With luck, he'd pick up good-paying work as a test driver for race cars.

Then he pulled up in the moving truck that day in January 2012. He had been drinking. The Jeep he was supposed to be towing was missing. He hadn't realized that it had broken loose over a bump, somewhere in San Bernardino.

The Highway Patrol found it the next day about 50 miles back.

People who loved order loved Irvine. Candy loved her hometown.

Tom was immediately ill at ease in America's safest mid-size city. It was easy to get lost amid the immaculate parks, gated community pools and shingled clubhouses.

Carefully ordered ranks of sycamore and eucalyptus trees flanked the streets, but the leaves somehow never seemed to clutter the clean white sidewalks, as if the city masterminds had arranged for them to vanish in mid-descent.

Candy writes a to-do list for her husband, Tom, as they prepare to pack up and move out of their Irvine home.

"Creeps me out," Tom told her.

These people have no idea what is going on in the world, he said of their neighbors, just as he did when she put on "Jersey Shore" or "The Real Housewives of Orange County."

She figured this was a big adjustment for him. He'd spent his 20s living out of a suitcase, traveling to auto races, and the first half of his 30s going wherever the Army told him.

Now he was the head of a household, subject to the emotional needs of a wife, an infant and two stepdaughters in a house always surging with activity.

One night, they attended a concert at the House of Blues in Anaheim, and the crowd made him panic. He raced away, breathing hard, saying, "I need it quiet, I need it quiet."

For all the horror he'd seen in battle, she knew that Tom longed to go back. He missed the camaraderie and adrenaline and the smell of sweaty combat gear. Sometimes, he admitted, he missed the freedom of the war zone and the power of an armored truck and a machine gun. "You are Billy Badass, and you sort of own the streets," he said. "It's elementary, but it's cool."

Maybe, she thought, that was why she came home from work every day to find him playing "Call of Duty" on his Xbox. Maybe that was why he watched "Restrepo," the documentary about American troops in Afghanistan, in an endless loop. And why he kept returning to his laptop video montage of the 1-4 Cavalry at war: seized bombs, blindfolded insurgents, and corpses, with a hard rock soundtrack.

When a metal bracelet came in the mail bearing the name of an Army buddy who had killed himself, she hid it, but he kept asking about it. Finally she gave it to him. Soon he was drunk again.

He needed alcohol to sleep, he insisted, and to forget. She would discover him sitting by himself, his eyes vacant, his speech slurred. He'd mix liquor with antidepressants and forget how many pills he'd swallowed.

She stopped inviting him to get-togethers. She made him sleep in the living room. Once, she came home from work and found him on the couch, out cold, clutching a loaded gun under his ear.

After her family is evicted from their Irvine rental home, the job of packing up falls mostly on Candy as her husband descends deeper into depression.

A WIFE'S LONELY STRUGGLE

Later, the months after Tom's return would merge into a blur of gray rooms and cheerless buildings: short-lived rental homes, hospital wards, storage units, jail corridors, welfare offices. Hopefulness was her strength, but she seemed to surrender more of it in every lonely place she pushed her stroller.

She pleaded with the Department of Veterans Affairs to give him a bed in rehab, but he couldn't stay sober for the required two weeks. One day he was found sobbing in his car outside the VA's Long Beach campus, and was taken to the ER for psychiatric evaluation. He fled when he realized they wanted to keep him for a few days, long enough to detox.

Doctors diagnosed him with post-traumatic stress disorder, though he didn't believe it. More than once, he remarked that she would be better off with him dead.

With Tom unable to work, she put out feelers for a better-paying job, even though she cherished her three or four days a week at the center for developmentally impaired children. It was intense work, and for a few hours, she didn't think about what might await her at home.

He picked up two DUIs in rapid succession. She confiscated the keys to his Jeep, hid his credit cards, hunted down and destroyed his booze stashes.

He would recall little of the day he tried to kick down the door, beyond the fact that he came home to find it locked and she wouldn't let him in. For her, the memory would be vivid. How she stood inside with Blake in her arms, frightened. How he shouted something incomprehensible in Arabic, his eyes fixed on her but somehow not seeing her.

"Tom, it's me! It's me! Stop!" she yelled.

The glass cracked, the wood splintered, and the door began to give.

She called the police. They calmed him down. They left her with a husband she no longer recognized, and a doorway littered with glass.

Then he vanished. It happened on the day she rushed the baby to the hospital with pneumonia. She stood in the pediatric intensive care unit, repeatedly dialing and texting Tom.

She suspected the truth even before it was confirmed. Another bender, another DUI.

When he finally called, later that day, he was only hours out of lockup. She assured him their baby was fine. No, she didn't want him at the hospital.

Tom looks at a photo his wife sent of their son, Blake, who was being treated at the hospital for pneumonia. Police had impounded Tom's Jeep after his latest DUI arrest.

"Please send me a picture," he said, alone in their new rental house. They had moved there after being evicted over the wrecked door.

"I'm worried about you and what you're gonna do tonight," she said. "Will you be home tomorrow when I come home?"

"Where am I gonna go?"

She told him she loved him, and then looked at the phone in silence and wondered why Tom wasn't replying. Finally he said, "You realize you're never gonna see me again after tomorrow?"

"What do you mean, I'm never gonna see you again after tomorrow? I don't like it when you talk like that."

He was talking about having to do time for the three DUIs. "I'm probably never gonna see my kid again," he muttered.

"I don't think it's gonna be that bad," she said. "We'll figure it out. But it has to be your last. You know that, right?"

She said "I love you" again and waited for him to reply. After a long silence he said, "How can you possibly love somebody like me?"

"Because I know who you really are," she said. "I know you're gonna be OK. OK?"

She told him that she was through with half-measures, that he had to check into a rehab center.

"You need to go away for a couple of months," she told him. "I don't even think you know what it feels like to be happy anymore."

"I don't know what it feels like to be happy anymore," he said. "I don't know what it feels like to be healthy anymore. Not even close."

But he hated the idea of being locked away in rehab, separated from his family. How would he support them?

She told him he wasn't helping anyway.

"If you want to stay married, if you want to stay in contact with your son, if you want to stay out of jail, this is your option," she said. "I love you, but enough."

The next day, they paid $250 to get the Jeep out of the tow yard and arranged to sell it at CarMax,

Candy gives husband Tom directions to the car lot where she is trying to sell his Jeep. On his Army base in Kansas, he would drive the Jeep around with an open bottle of whiskey in the cup holder.

He knelt before the black slab with the names of Americans killed in Iraq. He found the men he had served with. They were in their 20s, most of them killed by roadside bombs. "Rushing you to the hospital was the worst day of my life," he told one.

He touched other names. He talked to them. He heaved.

By the time he returned home, past dark, Candy had discovered his stash of beer and was throwing it away. He insisted that she give it back, or he would go buy more.

"I'm probably gonna get like another DUI," he said.

"You don't have keys to your car. I have them."

"God," he said. "You have no idea what I'm capable of."

"What does that mean?"

"Either leave the alcohol here, or watch me do something more stupid."

"I'm sorry, I'm not gonna contribute to this problem by leaving you alcohol," she said. "If you go to jail, don't call me from jail."

"No worries," he said under his breath. "It's only gonna cost the family more."

She demanded to know what he meant. He didn't reply. She asked again. No response. She left with the kids. They would spend the night with a friend.

'MAYBE THIS IS MY LESSON'

In three months, the homecoming had come to this:

Oversized garbage bags, stuffed with their clothes. Moving boxes, stacked in their SUV on either side of Blake's car seat. An air mattress on the floor of their still-empty new house, a few blocks from the first.

They were just back from Public Storage, where most of their belongings were still crammed.

"Hopefully, we don't move for like five years," she told him. "I don't want to move."

In the empty home, Tom held his son. He kissed him tenderly. At night he watched "Restrepo" and played "Call of Duty," filling the room with the sounds of screaming and chopper blades.

"It was freezing in this house and I kept getting bumped off the air mattress," Candy complained in the morning after a bad night's sleep.

"On the Syrian border we had a broken heater for four freakin' months," Tom said.

"That's great, but I'm not in the Army," she said. "We have a baby."

"Toughen him up," Tom said.

He asked his VA social worker for a referral to Combat Veterans Court in Santa Ana, a program designed to divert former war fighters from lockup and into treatment.

The presiding judge, Wendy Lindley, sent him to county jail while lawyers weighed the charges. She made it clear that he was either going to stay in lockup or enroll at Beacon House, a last-resort rehab program that would entail a separation from his family of nine months, or more.

Candy pushed Blake's stroller into the central jail in downtown Santa Ana, through the metal detector, into the inmate visiting room. She felt humiliated, judged by everyone. She hated it here. She was afraid. She looked at Tom through the plexiglass.

She told him she would not bail him out. She had a lawyer friend draw up divorce papers. An ultimatum.

After two weeks in jail, he agreed to Beacon House.

And so on April 24, 2012, Candy sat on a wooden bench in Judge Lindley's courtroom next to the glassed-in cage where Tom waited among other inmates, his expression desolate, his long body hunched forward in extra-large jail scrubs.

The judge told him he was endangering the people of Orange County by driving drunk, and was out of chances.

Tom faces an Orange County judge on DUI charges. During the hearing, he asks for his case to be transferred to Combat Veterans Court. The judge consents.

"It is no excuse that you are a combat veteran," the judge said. "You are a mess."

Now the judge looked right at Candy, explaining that it was important to understand Beacon House's strict no-contact rules.

No visits. No phone calls. Not even a glimpse of him across the room.

She would be completely cut off from him. Any family communication, by the program's logic, might derail his progress. Tom must feel what it is like to lose everything.

"He is fighting for his life," the judge said.

"I, I understand that," Candy said.

She wanted to say goodbye, but when she tried to talk to Tom through the window, a bailiff stopped her. No communication allowed.

Outside the courtroom, she spoke as if she was the lucky one. "I'm not going through it. I'm not the one sitting there shackled," she said. But she knew this was only partly true.

She was already counting the time without him.

Two days ...

She was standing at the counter of an Irvine post office when her vision reeled and she started sweating. She was conscious of Blake, now 9 months old, crying in his car seat, and of Addy, 7, storming around the room. She was aware of people staring. She felt she was suffocating. She fixated on one word: "Breathe ... breathe ... breathe ..."

Because she had married a soldier and was accustomed to saying goodbye, the nature of her situation took some time to sink in.

She decided the panic attack was her body sending her a message.

"You're all alone," she said.

Three days ...

A letter arrived, written in pencil.

My loving wife,

I feel ashamed, guilty, selfish and pathetic for not being a stronger and more supportive man, husband and father. I’m truly, truly sorry for letting you down & hurting you. I hope I can make it all up to you in the decades ahead during what I believe will be a strong & beautiful marriage. I wish & pray that you’ll be able to find it in your heart to forgive me someday. I promise you that from this day forward I will spend every day working on being a better man for my family.... I don’t know how you balance the baby, the girls, work, bills, house, job hunt, moving and so on without me.... You mean the world to me babe and you always will. I love you.

He'd written it while still in jail. She didn't know when she would hear from him again.

He was only an hour's drive away, but she already felt like a war widow, more distant from him than when he was in Iraq.

Yet she had to admit she was relieved he was gone, and this filled her with guilt, because she remembered the brokenness in his voice and how he had never been deliberately cruel, even during the worst of his meltdown.

"He's not out cheating, he's not saying mean things to me," she said.

Sometimes she popped a Xanax for anxiety, or Ativan to sleep, but she resisted antidepressants; she feared losing what she called her "super-happy times," a treasured part of herself.

Sometimes her worries closed in, like a fist. Would she be able to pay the $2,700-a-month rent on their new Irvine house, which had three bedrooms and a small courtyard, just enough room for Blake to play in? How would she find another place if she was evicted again, considering her credit? What if she became homeless and Social Services took her kids?

"I've made it this far," she said. "I can't be homeless. I don't have any option other than to figure it out."

She had filed claim after claim with Veterans Affairs for Tom's full disability benefits, but the VA backlog was notorious, already a dark national joke.

"I don't get how they think we're gonna survive — the VA, government, society," she said.

With son Blake nearby, Candy looks through her bills. To her, Irvine meant security and stability, and she clung to her home there at all costs -- even if her family had to go without gas or water for a time because of the high rent.

Two months, two weeks, one day ...

She could be mistaken for any other Irvine mom, sitting poolside in the dappled sunlight of a fine summer afternoon. Before her, Addy swam practice laps with her teammates. At her feet, Blake studied pill bugs. Behind her, hamburgers and hot dogs cooked on a grill.

This was the gated neighborhood pool where Candy swam as a girl, and her swim team photo hung in the clubhouse. Her whole life was here, as were her kids' lives, which was why she wouldn't move to a cheaper city. Irvine was security and stability, and she'd cling to it at all costs.

She tried not to cry in front of her kids. She did it in her car, where it was safe.

"I'm not even treading water," she said. "Just my lips are sticking out of the pool."

She had hundreds of acquaintances, some of them draped fashionably on the deck chairs around this pool now, but almost no one was aware of her plight. If people asked about Tom, she said he was in treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder and alcoholism and tried to leave it at that.

Certainly she wasn't confiding the full sorry story to the moms with the brand-new Escalades and designer purses and glows of surgical youthfulness, the elegant moms who had twice-monthly dates at the hair stylist, just as she'd had through her 20s and most of her 30s, before she started yanking her locks into the pragmatic ponytail she wore now.

She wasn't about to tell them her family had gone days without gas or water, and had showered at a friend's house.

She wasn't going to tell them about driving to Costa Mesa and entering a pawnshop for the first time, a place she associated with desperation and drug addiction, where she sold Tom's combat knives and a World War II-era radio that had belonged to his grandfather.

Or about having to sell her wedding ring for quick cash, and — just as painfully — the Tiffany necklaces her daughters had given her for Mother's Day.

Or about the humiliating card she now carried, which looked like a credit card but bore the words "Golden State Advantage" and entitled her to $500 a month in food stamps. Was she just imagining people's eyes on her at the Trader Joe's checkout line when she pulled it out of her purse?

"It's a card, so no one knows," she said. "But I know."

She was a proud lifelong Republican, a believer in grit and self-reliance, and this reversal made her question the unspoken superiority she had felt during her years organizing charity food drives. "Maybe in my own head I was a little judgey about it," she said. "Maybe this is my lesson."

Her Facebook friends mocked and derided people who owned iPhones but who claimed to need public assistance. They didn't know she had become one of them.

She could expect 30 or 40 "likes" when she posted a photo of Blake on Facebook, but few cared when she linked to a story about veterans. It made her think of her grandmother's stories about World War II, of how cheese and nylon were rationed and every family seemed to have a son or a neighbor in the fight.

"This war has been going on for so long, and they don't get it," she said. "This is not a war you or I have to sacrifice for unless you have someone in it. If you don't want to think about it, you don't have to think about it."

Solitude made her brood and worry, so it was good to be out here among the other Irvine moms, despite the invisible gulf that now separated her from them. The balmy air was good to breathe, meat grilled poolside, and kids swam through the early-summer light.

Two months, three weeks ...

The information blackout seemed increasingly ludicrous and cruel. At one point, by her count, she had left 10 unreturned messages with Beacon House. Even when she managed to get someone, the news was only, "He's doing great."

She fought the compulsion to drive to the rehab house and steal a glimpse of him. "I need to see physically that he's alive," she said. "My mind has played this trick on me. It's like he's dead."

She received word that he would be driven to the VA's mental health wing for an appointment. She devised a plan: A trusted friend would take surreptitious photos of him in the waiting room. Surely Tom would appreciate a stealth recon mission.

Tom recognized Candy's friend immediately and alerted his Beacon House minder. The plan was torpedoed. Tom seemed terribly afraid of upsetting the program.

What is happening to my very brave husband? she wondered.

Three months ...

Doctors removed the tip of her cervix after diagnosing her with cancer. She was home the same day, with the promise of a full recovery. But she had a new worry: What if she died, and Tom emerged from treatment no better? What would happen to her kids then?

Six months, three weeks, two days ...

She pulled the Ford Expedition up to a stoplight outside the VA's Long Beach campus. The SUV was 14 years old, with a sticker that said "Iraq Veteran." Waiting for a green light, she put it in park to keep it from stalling. It needed a new engine, a $2,000 proposition. She kept it running on luck and favors.

For months now, she had been trying to add her kids to Tom's VA health benefits, and to increase his disability rating from 80% to 100%. She had called the VA relentlessly, but couldn't get answers to what seemed the simplest questions.

"This is money he's entitled to. It's not like it's welfare," she said. "People get welfare faster than disability compensation."

In ways, she considered herself lucky. Her kids were healthy, and she found her work meaningful. But she felt guilty, somehow, when she caught herself actually enjoying her life — like watching Lizzie's cheer squad performing at the Veterans Day parade at Disneyland — because Tom was not around to share it.

She felt guilty about other things, like the little ways she stole a few minutes' extra sleep for herself. Instead of cooking Addy a full breakfast, she kept a Clif Bar and nonperishable milk in the truck's cup holder, so they were ready on the way to school.

She had been assembling a book of photos documenting each day Tom had missed of his son's life. Blake's first lollipop, first bite of cake, first apple, bumps on the head.

Now, she pushed Blake through the parking lot into the VA lobby. She found an elevator and headed down a series of corridors. The building made her anxious. She had spent too much time here.

She found the Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation Enduring Freedom veterans transition center. The friendly man at the check-in desk gave Blake a Hot Wheels car and cookies.

About 4:30 p.m., after hours of waiting, she was shown into a little office where she sat across from another friendly man, a benefits manager with graying hair.

He searched his computer, but could find no evidence of the claims she had filed.

"Is there any way you can help me with his e-benefits account?" she asked.

"I would love to, but without permission of the veteran, I can't," said the man. "Can you call him?"

"I can't."

He explained how a claim wended its way through the VA system. He had the patient tone of a man who had given the talk before, and would give it again every day until he quit.

"The claim is received in the mail room, and goes to the triage team," he said. "And then to the predetermination team, and then to the rating team, and then to the notification team." He added, "That is the final stage of the process."

He was so nice that it was impossible to be angry at him.

"At least I know what I'm waiting for now," she said.

Afterward she pushed Blake down a series of corridors until she found office No. K-127-C.

She wanted a look at the woman who had recently become Tom's new case manager for Combat Veterans Court, the woman who got to spend time with her husband while she, the wife, was banished.

Maybe it was silly, but she didn't want her to be too pretty. She peeked in the door, but couldn't get a good look.

She pushed Blake back through the parking lot and lifted him into the truck. It was another wasted day at the VA. For a veteran's wife, it was always the same. Everyone was sympathetic, and you waited forever, and nothing could be done.

Eight months ...

Under the Christmas tree sat donated gift baskets. She didn't tell her kids they had come from strangers. Her family had been adopted as a charity case for the holidays. The donations came with Target gift cards. She sold them for $300 and paid the electric bill.

Nine months ...

The VA came through. Tom's disability ranking was increased to 100%, boosting the monthly check from $1,700 to $3,340. It had taken Candy months of badgering, and some dumb luck. She had randomly dialed VA numbers one day, and she had reached a claims manager's assistant.

The money was a great relief, especially since her wages were now being garnished as a result of a court judgment stemming from the door Tom kicked apart at the rental house. They owed $20,000 for property damage and the unpaid remainder on the lease.

She called and yelled, but Beacon House would still not tell her when Tom was coming home.

She showed Blake photos of his father. They kissed the photos.

ONE MORE CHANCE

Nine months, two weeks ...

What if he didn't want to be part of their noisy, bustling, unruly family? What if he couldn't be fixed, or didn't want to be?

Her phone rang. It was Tom. Beacon House was bending the rules a little, he explained. They had seven minutes.

He told her he wanted to be a good father, and never wanted his son to see him drunk. She kept sobbing and telling him she loved him.

Ten months ...

Friends kept asking: What if Tom comes home and relapses?

"I'm not giving him a third chance. I will not hesitate. I will be gone. This is not going to be the rest of my life," she said. "He already got more than anyone else would have gotten in my book, so that's his chance."

She'd made other decisions. She would not have any more kids, even if he begged. Blake still woke her up at night, and she was tired in a way she hadn't been with her first two kids.

She'd also decided that she'd never lose another argument with her husband. If he complained about anything, ever, she'd silence him with the two words that summed up what she'd endured: "Beacon House."

She knew his rehab program was built on structure. Tom was up at 6:30 a.m., then breakfast, chores, meetings. But how would he handle the whirlwind of what she called "our very busy, crazy, chaotic life"?

Lizzie was 17, dashing through the house from cheer practice to the pizza place where she worked as a hostess. Addy was 8, dancing across the living room or chasing the cat. Blake was nearly 2, climbing on everything, finding new ways to injure himself every day.

But there was good reason to hope now, wasn't there? He'd been sober for almost a year. And he'd have to submit to regular urine tests as a condition of his probation, which meant she wouldn't have to police him. He had learned. He must have.

"I want this to be a happily ever after," she said.

Eleven months, three weeks ...

She waited for him in an Irvine park. She would have 10 minutes with him, under the watch of a program chaperon. She saw him walking across the grass and ran to him.

He recited his sins and apologies. This was the making-amends part of his recovery, and his tone struck her as a little robotic, but he looked great, sober, lucid, clear-eyed, and she got to kiss him.

He wasn't supposed to stray from the script, but he had to tell her how scared he'd been. When cars pulled up at Beacon House, he thought she was sending divorce papers.

One year, two weeks, two days ...

Tom would be coming home tomorrow. She was digging through boxes in the garage for a pair of heels, but could find only mismatches. Tonight she would shave her legs, for the first time in a year. In the morning she'd apply mascara, curl her hair and put on a black dress.

She could see it. She would attend Tom's Beacon House graduation ceremony in San Pedro, and lift her son into his father's arms. Then they would drive home, and they would live as a family. Their life as husband and wife would finally begin.

Would it?

She remembered how hopeful she'd been, 16 months ago, as she waited for him to pull down the block with his moving truck.

To make room for Tom's things, she was cleaning out closets and cabinets. She didn't expect to sleep tonight. She wondered if Tom would be upset with her for decisions she'd made over the last year. Would he be angry, for instance, that Blake was still spending nights with her in bed? Would he question how she'd handled the family money? Would she bite his head off if he dared to criticize any of her choices, considering his absence?

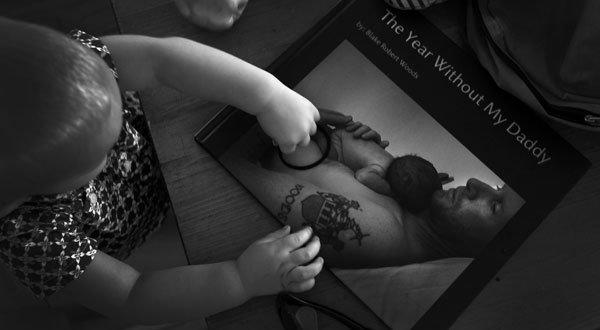

The book of Blake's day-by-day photographs was ready. "The Year Without My Daddy," it was called. The boy had his mother's blond hair and his father's blue eyes.

She had been drinking health shakes, trying to slim down. Would she still love him? Would he still be attracted to her? She caught herself and said, "Here I am, still worried if he's gonna love me. That shows I do love him."

She had fixed the flagpole holder out front, hammering in the nails. She had purchased new light-blue bedsheets. She had poured the wine down the sink. She had left his cavalry Stetson on a living room shelf, to greet him.

"I feel like he's normal, he's OK, that he can come here and be OK," she said. But she knew the war always found new ways to punish people, and no one could say whether love or war would win, least of all a soldier's wife.

One year, two weeks, three days ...

A car came down a quiet block in a fine city in a country at war. It pulled up to a two-story brown house on the corner, with a big American flag and welcome-home signs and patriotic balloons out front. Husband and wife climbed out. They walked to the front door, arm in arm. Then they entered together.

Contact the reporter | Follow Christopher Goffard (@LATChrisGoffard) on Twitter

Contact the photographer | Follow Rick Loomis (@RickLoomis) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

About this story: Times staff writer Christopher Goffard and photographer Rick Loomis followed the Woods family for a year and a half, beginning in March 2012. One or both of them accompanied Candace Desmond-Woods to court hearings, on jail visits and to the Veterans Affairs campus, the neighborhood pool, the pawnshop and other places depicted in the story. Audio or video recordings were used to ensure the accuracy of extended quotations.

Additional credits: Video Producer, Spencer Bakalar | Video Co-Producer, Liz O. Baylen | Web Producer, Evan Wagstaff | Digital Layout, Stephanie Ferrell

Also by Christopher Goffard and Rick Loomis