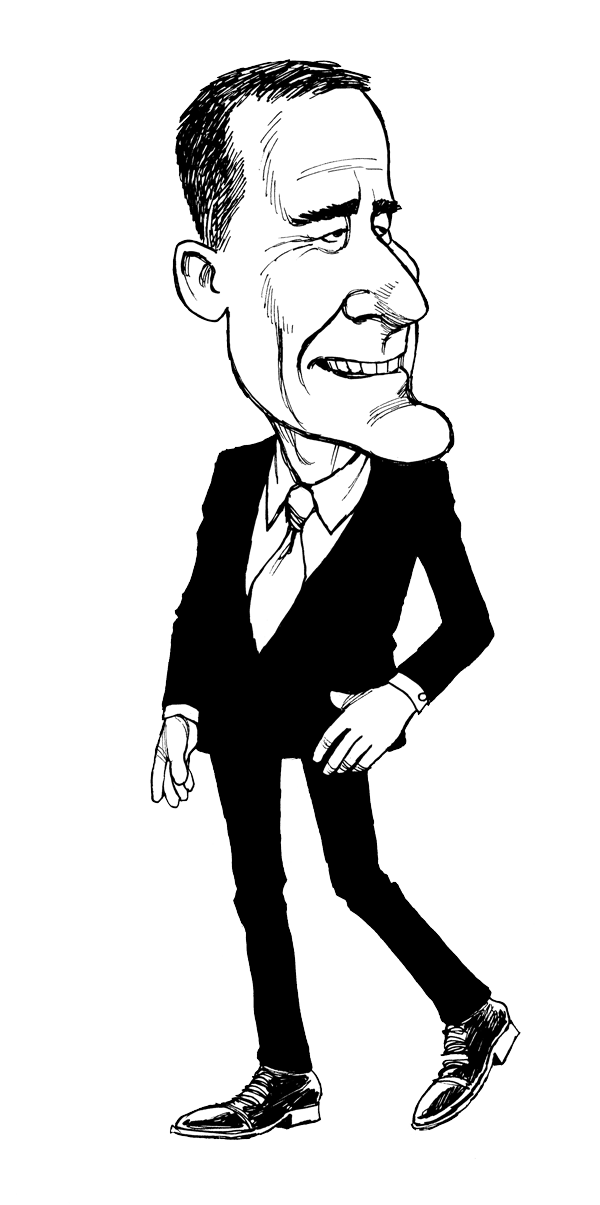

NAME Eric GarcettiOFFICEMayor |

|

|

|

NAME Eric Garcetti |

OFFICE Mayor |

Two years ago, when The Times endorsed Eric Garcetti for mayor, we described him as the candidate with the most potential to lead Los Angeles into a more sustainable and confident future. But we had concerns too: Garcetti should not confuse constructive compromise with the path of least resistance. He should not try to be "all things to all people." We worried that he was "hard to pin down" and called him "a bit of a Zelig."

Today, unfortunately, our concerns are becoming reality. Midway through his first term, Garcetti remains as appealing and articulate as ever, but his inclination to avoid tough or controversial decisions is undermining his ability to address the very serious problems facing the city.

Garcetti has presented a vision of Los Angeles as a more livable, transit-oriented, environmentally and technologically friendly city, served by a more efficient, customer-oriented government. This is a good vision, and he is an eloquent spokesman for it. But what has he done to achieve it? So far, not much.

| CATEGORY | GRADE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Overall |

|

Garcetti said repeatedly on the campaign trail that job creation would be his top priority. After all, the city has never recovered the middle-class jobs it lost over the last three decades with the shrinking of the aerospace and manufacturing sectors. Immediately upon taking office, he announced a nationwide search for a deputy mayor for economic development. But in the end, he chose to surround himself with political allies rather than nationally recognized experts, hiring his longtime council staffer for the deputy mayor position and putting former Councilwoman Jan Perry in charge of the Economic and Workforce Development Department. Two years later, unsurprisingly, the mayor has yet to articulate a comprehensive job creation strategy.

And after signing into law a modest break for just the highest-earning firms, he's all but dropped his campaign promise to completely eliminate the city's business tax, even though companies say it's the chief reason they won't locate in Los Angeles. This is how he leads on his No. 1 priority?

Likewise, the mayor laid out what he called a "back to basics" agenda aimed at restoring city services that had been slashed or ignored. However, he killed a sales tax proposal to fund street resurfacing and sidewalk fixes, and he's never offered an alternative proposal to pay for the multibillion-dollar backlog of repairs. He has set an ambitious and worthy goal of reducing the city's dependence on imported water, which will require enormously expensive investments in cleaning contaminated groundwater, recycling wastewater and capturing stormwater instead of letting it flow to the ocean. Yet last month, when the Department of Water and Power proposed raising rates to help pay for infrastructure replacement, Garcetti played coy, saying, "Before I agree on an exact amount of an increase, I want to hear what our customers have to say and get the analysis from our ratepayer advocate." Of course, this is insincere. Garcetti appointed all the DWP commissioners and hired (and can fire) the DWP's general manager. Garcetti's office was involved in developing the rate proposal. He should make an honest case about the city's infrastructure needs and what it will take to pay for them.