How the Katrina survivors

we reported on 10 years

ago are doing now

Hurricane Katrina made landfall on the Gulf Coast 10 years ago on Aug. 29. The national drama that unfolded once the storm passed left more than 1,800 people dead and caused an estimated $151 billion in damage. The Times interviewed hundreds of survivors in the immediate aftermath of Katrina. We got in touch with several of those survivors this week, including the subject of our most memorable Katrina photo: Dillion Chancey, who was 7 years old when his image was captured by Times photographer Carolyn Cole days after the hurricane hit.

Katrina anniversary full coverage »

The photograph was a snapshot of desperation: a tawny-haired boy wearing nothing but a muddied pair of shorts, sitting on top of a collapsed fence in Biloxi, Miss. Mounds of debris filled the frame around him. He held his head in one hand and a soggy, face-down teddy bear lay at his feet.

The image, which ran Sept. 1, 2005, on the front page of The Times, showed how Hurricane Katrina had laid waste to the Mississippi coast, a place where thousands were displaced and few journalists had ventured as the focus stayed on the devastation in New Orleans.

It also captured the moment 7-year-old Dillion Chancey realized what he had lost. Dillion, along with his parents, had clung to treetops and neighbors’ rooftops to withstand the deadly storm surge after his home disappeared under the debris. A couple days earlier, Dillion had complained to his mother that there was nothing to do.

“You’ve got a room full of toys,” his mother, Sarah Fairchild, remembers chiding. “So many children in the world don’t even have that.”

Now he sat on the felled piece of fence, another child’s abandoned bear next to him, stunned into silence. “Mama, I really don’t have any toys now,” he said. “We’ll get more,” Fairchild told him.

They did, but it took a long time. Fairchild and Dillion’s father, Bobby Danny Chancey, got to work helping locals repair damaged roofs and rebuild homes that had washed away along with their own.

In the 10 years since Hurricane Katrina, this family has struggled, taking up residence in a trailer and then a mobile home, taking odd jobs, and making ends meet at times with the kindness of strangers and the generosity of one wealthy Pasadena man.

“If you can believe it, we’ve never really cried at any point” in the 10 years that have passed, Fairchild said. There was no room for that. “After making it through the storm itself, I figured there was a plan for me and I just had to take it a step at a time, a day at a time and get there.”

Fairchild, who made decent money as a dealer at a casino before Katrina, took jobs at a Dollar General, Hobby Lobby and Waffle House. The couple, who never married, tried to get ahead by starting a business rehabbing flea market furniture, but it went belly-up about a year later. Even so, Fairchild said, “We’ve managed day to day for our basic needs.”

“We came a long ways,” Dillion, now 17, said this week. “I didn’t even have no clothes after Katrina. I had the pair of shorts that I had in that picture, and that was it. I got clothes on my back now.”

As Katrina’s 10th anniversary approached, teachers at his high school asked students to talk about their storm memories, and Dillion pulled up The Times’ photo on his phone. He said his classmates, some of whom had seen Katrina’s devastation firsthand, were still awestruck by the image. The teen has seen the photograph all over the Internet, but he doesn’t often look at it. Asked this week to describe the moment captured in the photograph, he said it’s hard for him to talk about.

“It don’t bother me to look at it, but it’s not something I turn back to every day,” Dillion said. “Really, I feel that it’s a part of my past, and that’s where I like to keep it. It ain’t something I’m going to sit and cry about.” Besides, he said, plenty of people on the coast struggled.

Fairchild, 47, credits God and the generosity of strangers for the family’s survival since the storm. After The Times ran a front page story about the family, dozens of strangers sent them letters, Fairchild said, some with checks for $50 or $100. “Buy something for Dillion with it,” notes said. Many asked how they were faring, if there was anything they could do, if Dillion had a bicycle to ride. The random kindnesses lasted about a year.

Art Gastelum, a Pasadena business executive whose company manages government construction projects, also saw the story. “I saw that photo and that little boy just over a pile of trash, with his head down. Like the thinking man,” said Gastelum, referring to Auguste Rodin’s famous statue.

Gastelum, a former lobbyist and longtime aide to former Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley, couldn’t get the image out of his mind. “It just broke my heart,” he said. He flew the family to California to send Dillion and his parents on their first and only trip to Disneyland.

“I didn’t make it through all the rides,” Dillion remembered. “But I know I didn’t like that Space Mountain one…. Maybe now I would.”

They stayed several days, and Gastelum gave the family a 27-foot-long motor home, which they drove back to Mississippi in late October 2005. Fairchild remembers stopping in San Antonio on the way home for Halloween, so Dillion could go trick-or-treating.

For nearly two years, the family lived in that motor home on a pine-filled property they owned that was farther north than their destroyed home -- and farther away from the water. Now they live there in a former shed that Chancey, 57, crafted into a two-bedroom house. Fairchild has envisioned building her dream home there, with stone on the outside and a wraparound porch. So far, only the foundation has been poured.

Fairchild says she’s hoping to change that. Three years ago, she was able to get a casino job again, and with Chancey’s steady handyman work, the family is on more stable ground. “Soon, maybe, we’ll be able to make a big step in that direction,” she said.

As for Dillion, “He’s got a good head on his shoulders. He’s tried to do right and be a good person,” his mother says. Dillion fell behind in classes this spring, and is retaking some sophomore year courses, but has assured his parents he’ll be on track by year’s end. Over the summer, he took a job at a shrimp factory in Biloxi. He saved enough money to buy his first truck, a 1994 Ford F150, and hopes to get his driver’s license soon. Dillion loves fishing and being outdoors and says he wants to be a game warden to help regulate hunting and fishing.

“We just had hope that we would get to the future, get to where we wanted to be,” Fairchild said of her family. “We’ve stuck together.”

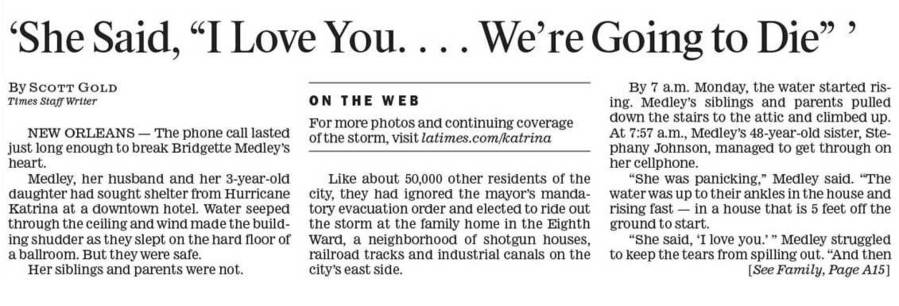

The morning Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, Bridgette Medley got a panicked phone call from her sister, who was trapped in a rapidly flooding home with their brother and elderly parents.

“I love you,” Stephany Johnson said, and then, “We’re going to die.”

The line went dead.

Medley was riding out the storm on the hard ballroom floor of a downtown hotel with her husband and 3-year-old daughter, but her sister, parents -- Barbara and Paul Johnson Sr. -- and brother, Paul Jr., had decided not to evacuate their house in the city’s 8th Ward.

As the home filled with water, her relatives sought higher ground, eventually finding themselves stuck in their hot attic.

By the time Medley told her story to The Times that evening, her sister had called again with welcome news: The National Guard was sending a boat.

Medley was beyond relieved. She vowed her family would stick together from then on.

But that isn’t exactly how things worked out.

The Times spoke to Medley again this week. Here’s what she said had happened since:

When the rescuers came to save Medley’s relatives from the attic, her father refused to leave. He wanted to protect his home.

“He had worked hard to get it, and he didn’t want anyone coming in,” Medley said.

She said her brother refused to leave their father’s side, so her mother and sister boarded the boat and said their goodbyes, unsure of when they’d meet again.

The two women ended up at the tattered Superdome, where more than 20,000 people had sought shelter.

The stadium was soon evacuated. Medley’s mother and sister ended up in Huntsville, Texas. Days later, as they watched more people arrive, the mother said to the sister, “Go help your daddy get off the bus.”

“Yeah, right,” she replied, not believing that her father and brother had wound up in the same place. But there they were.

Two days after refusing to leave the home, the two men had agreed to hop on a rescue boat, which left them on a highway on higher ground. They caught a ride out of town on a bus -- a bus that happened to be heading to Huntsville.

Meanwhile, Medley and her husband, Lester, and daughter pingponged around the South. Her husband’s job as a news photographer took them to Louisiana’s capital, Baton Rouge. Then Medley went to Atlanta to meet up with her other sister, Gail Joseph. She headed to North Carolina when she learned her in-laws had evacuated there, and then she returned to Georgia.

It would be five years before Medley’s whole family would be living in New Orleans again.

Medley’s parents and sister Stephany settled for a time in Houston after her father, suffering from dehydration and chronic heart disease, was hospitalized there. Medley joined them in October. Her brother remained in Huntsville, an hour north. Her sister Gail stayed in Georgia.

Medley’s husband kept working in Louisiana. She and her daughter went to New Orleans to join him in January 2006. It had been barely three months since the city dried out.

She came home to a waterlogged house, furniture and debris scattered everywhere. “It looked like my house had just exploded,” Medley said. The water line was 3 feet up the wall, and black mold seemed to engulf every corner. She remembers the stench as unbearable.

“It was dusty. It was moldy. You could smell the mold over the whole city” for months, she said.

For more than a year, Medley and her husband, daughter and mother, who had come to help out, lived in a one-room trailer parked next to the Medleys’ gutted home.

“It made it easy for my husband to work on the house,” Medley said, but that was the only upside. Each morning when he came home from his graveyard shift, he’d get to work rebuilding, slowly, plank by plank.

Medley, who had been an operating room nurse before the storm hit, couldn’t find a job. The hospital that had employed her shut down after it was flooded, and there were few others operating. So Medley worked part time as a school nurse.

On weekends, they’d pack up the car and make the five-hour drive to Texas to see the relatives who remained there. That was their routine for nearly two years.

Piece by piece, their home came together. They rebuilt, adding a den and an extra bedroom with the $100,000 they received from the state’s Road Home program, designed to assist residents with post-Katrina recovery. (Many others languished while the payouts were delayed.)

Slowly, more of her family members began to trickle back to New Orleans. Her father arrived in 2007 to a rebuilt house, this time with an extra bathroom. Her brother and sister Stephany rejoined them a couple years later.

Medley went back to school, earning her bachelor’s degree. Earlier this month, she started a new job as an operating room nurse again, at a hospital that opened just last year. It was built on the site of another hospital Katrina had flooded.

“I’m starting over with an institution that is starting over too,” Medley said.

Ten years later, some things remain unfinished. The floors of her home aren’t quite done, and the back of the house remains unpainted.

Her parents recently died -- her father in 2013, her mother last year. Her brother and sister Stephany live in their parents’ home now, and the family often uses it as a gathering space. The other sister still lives in Georgia but visits regularly.

“We stick together now,” Medley said. “As much as we can.”

Dr. Bryant King walked away from Hurricane Katrina, largely unscathed, and never really looked back.

He already had one foot out of New Orleans: In nine months, he was scheduled to begin a nephrology fellowship in Indiana. King, who now has a private practice in Indianapolis, had just finished his residency and was a newcomer to New Orleans’ Memorial Medical Center when the storm hit.

Four days later, in the devastation wrought by the hurricane, King would walk out on a sweltering hospital full of hundreds of trapped patients.

“I just thought to myself, ‘I got to get the hell out of here,’ ” King recalled to The Times this week.

FOR THE RECORD

Sept. 1, 2:03 p.m.: This post stated that the hospital was full of hundreds of patients when King left. Many of them had been evacuated by the time King left, and some reports said only a handful remained. By Thursday evening, all of the patients had been evacuated.

The hospital had been in a desperate state for days. With most of the city underwater, hundreds of patients were stranded, along with a cadre of doctors who had stayed to treat them. Electricity had been cut off when pumps that powered the hospital’s generators were flooded, and nurses were monitoring vital signs manually. Hospital staffers smashed windows to ventilate the building.

King later became associated with a controversy involving allegations regarding the actions of a doctor and two nurses at the hospital during the height of the storm’s chaos.

The day before King left, he said, a man and woman with a baby floated to the front of the hospital on a makeshift raft, pleading with the armed guard at the front door to let them in. The hospital wouldn’t. King said the couple begged someone to take the infant, and so did he, but the doors stayed closed.

King’s sister, whom he’d been communicating with by text message, posted a desperate plea on the online message board of the Times-Picayune newspaper. “My brother, Dr. Bryant King, is stranded there,” Rachelle King said. “Yesterday, he explained that management at the hospital decided to selectively withhold food and water from patients. Doctors are being forced to decide who gets to live and who will starve to death,” the message said. “My brother asked that we please get them out of there.

Bryant King left the day that significant help began arriving.

“People say that I abandoned the patients,” King said. “There’s no police, there’s no law.” King said he feared for his personal safety after objecting to what he saw, including the episode with the infant.

As soon as King walked out through the hospital’s front doors, he said, he was focused on getting home. A boater took him about 10 blocks before the water became too shallow to navigate. He walked a couple of blocks in waist-high water before reaching dry land.

King recalled that as he walked, he saw scattered packs of people roaming the streets. People armed with shotguns sat on porches, warning him not to approach. Bloated bodies lined the streets — he said he saw at least half a dozen. The stench of death was inescapable, King said.

“It seemed like a Third World country,” he said. “I had lived in New Orleans for 13 years, and I didn’t recognize it.”

But his West Bank neighborhood had remained dry, and three hours later, he arrived home to his neat but dark apartment, fully stocked from a pre-storm grocery run.

He took a shower, put on a fresh T-shirt and scrubs, and waited.

“I was perfectly fine,” King recalled. “It was like nothing had happened.”

King stayed in his apartment for two weeks, surviving on canned tuna, fruit and chips. He gathered downed branches, using a charcoal grill outside to boil his water after the local treatment plant was compromised.

“It drove me absolutely crazy to be drinking room-temperature water all the time,” he recalled.

Eventually, a friend was able to drive to New Orleans to pick him up. King said he went to Houston to see his girlfriend, then to Chicago because his mother wanted to touch his face.

He went back to New Orleans to retrieve his things and moved to Indianapolis soon after, working in the emergency room of a VA hospital as he waited to begin his fellowship. He’s lived there ever since.

King has returned to New Orleans a couple of times, for a friend’s wedding or other reunions. His friends there refer to the “P.K.” — or pre-Katrina — era. His current life seems a world away.

There was some recovery period, King said. For months, he said, he couldn’t remember basic things — account numbers, his address; he’d always been able to recall the minutiae of a patient’s care for months at a time. There was a recurring dream in which he, an avid swimmer, was drowning in deep water and couldn’t move his limbs.

King lives in a landlocked place now, on purpose, and always keeps a plastic tub stocked with basic supplies: a can opener, dry food, tuna, medicines, a battery-powered television and lantern. “I can deal with tornadoes and snow,” he said.

But he never again wants to live through the kind of widespread devastation that Katrina caused.

Every once in awhile, his mind wanders back to the dark days in the New Orleans hospital he left behind.

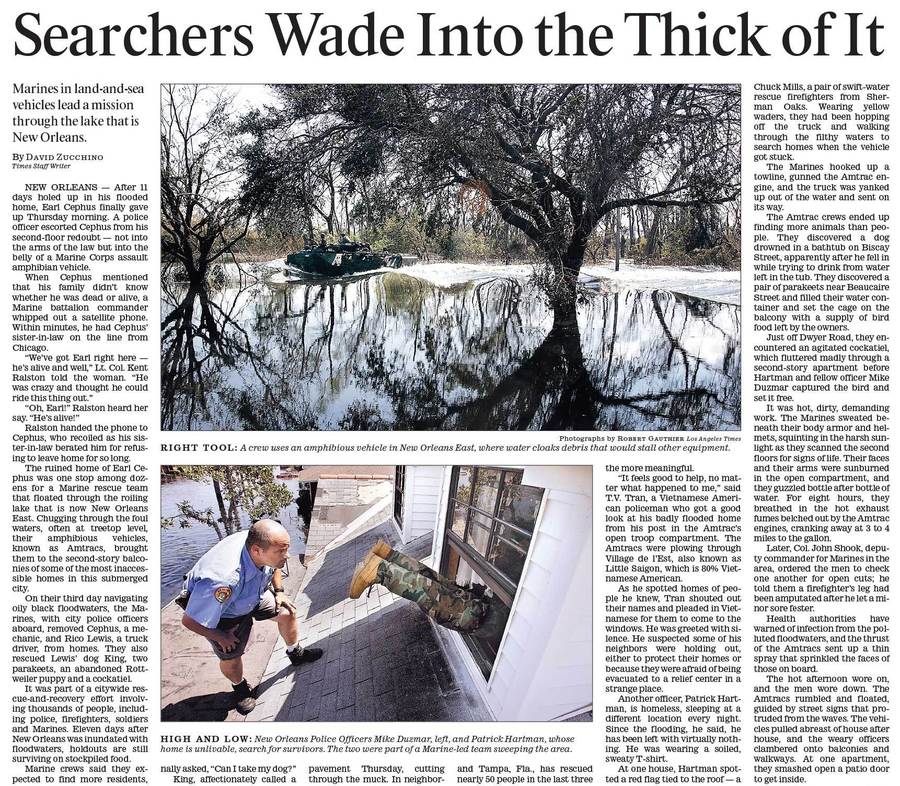

In the days after Hurricane Katrina tore through New Orleans, the city’s police officers still needed to run their operations from somewhere dry.

Michael Duzmal and his fellow officers found respite at the Crystal Palace banquet hall. During those hellish days 10 years ago, it served as a makeshift command center. It was cramped and filled with Army cots, he recalled. There was no air conditioning.

“I think we had one or two fans,” Duzmal, now a detective with the New Orleans Police Department, told The Times this week. “But it was where we were able to regroup.”

Each day the officers were given different roles, he said, be it rescue operations or patrolling to look out for criminal activity. They ate bagged military meals. The hours were long because they were short-staffed -- especially during the first week after Katrina hit -- and lacked vehicles because they were destroyed in the storm. Running on four hours of sleep was not uncommon, he said.

“It was literally go, go. There was very little downtime,” Duzmal said. “So you did the best you could. That was the roughest time, when we first hit the ground running.”

Duzmal said working during the initial recovery efforts was overwhelming, but he saw law enforcement and military agencies “at their best.”

At the time, he was 37 and had been with the Police Department for just two years. He still struggles to find the words to describe the experience.

“It was beyond anything I could have ever imagined I would be a part of,” he said. “It’s tempered me for the rest of my career.”

He added: “I don’t know how to explain it, but after you’ve been through that, not that the rest of it isn’t dangerous, not that the rest of it isn’t challenging … but other things don’t seem quite as stressful.”

A Times photo from 2005 shows him and another officer searching for survivors in a home with a flooded street in the background. The two were part of a Marines-led team sweeping the area.

The accompanying article says the team ended up finding more pets than people and did what they could to give the animals a chance to survive. It says that on one street, Duzmal and a fellow officer “encountered an agitated cockatiel, which fluttered madly through a second-story apartment before [they] captured the bird and set it free.”

A few months ago, Duzmal said, his job brought him back to that neighborhood in eastern New Orleans. He said he was stunned to see how many homes had been reoccupied.

“It made me feel good to be able to look at that area and not be confronted by the ghosts of the places that I had left,” he said.

A Chicago native, Duzmal said his adopted home “is back in business.” It’s once again a tourist destination. People, homes and stores have recovered. Duzmal attributes it all to New Orleans’ spirit.

“Because it’s the city it is, there is no other possible outcome,” he said. “The city is resilient.”

UPDATES

3:30 p.m.: This article has been updated with additional background and context.