Capt. Stephen Hill had a 23-year career in the Army and a secret that he felt he could never make public without throwing it all away. More photos

THE HIDDEN MAN

America saw Stephen Hill's face for 15 seconds.

It took him a lifetime to show it.

An American soldier sits alone in a wooden box in the desert, trying to erase himself. Off comes the Velcro patch that says CAPTAIN. Off comes the name tag that says HILL. He positions the camera so it will show nothing to betray his identity: just a chin, a mouth, and the words U.S. ARMY on the breast of his combat fatigues.

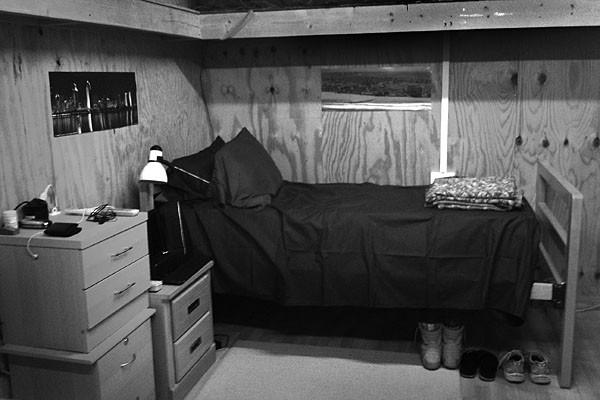

The box is a 10-by-10-foot room made of quarter-inch plywood, which counts as officers' quarters at this combat hospital in northern Iraq. He takes care not to show any of the personal touches on the walls. Not the taped-up note that reads, I love you. I'll never be able to show, say, write or send anything that can ever truly show you. Not the pinned-up chew toy bearing the teeth of his dog, Macho, or the stuffed Super Mario Bros. doll.

It is September 2011, in the waning months of the Iraq war. The soldier has duct-taped every crevice of his room, to keep out the harsh light and the endless gusts of desert grit. He still has a cough from Desert Storm, exactly half a lifetime ago. Because the walls are thin, he has chosen for his task an early-morning hour when he knows the soldier in the adjoining box will be away on duty.

He squares himself before his Sony laptop and hits record. The camera's tiny green light comes on. He swallows and begins talking. He stops, erases, starts over. He does it again and again, until he has a take he can live with.

Fear is a habit, and during his 23-year Army career he has seen what happens to soldiers who are careless. He clicks a button and sends off his 34-second message under a disguised email address. Maybe, he thinks, that will do the job. Maybe he can stay hidden in the lightproof, dustproof box.

Stephen Hill joined the Army just out of Upper Sandusky High School in north-central Ohio. He hoped to pay for college, because in the Hill family you paid your way. And he hoped to win the respect of his father, a former Marine who had come home from Vietnam with scars from the sharp elephant grass, and a hundred stories of peril and friendship. When he put on his father’s combat helmet, it swallowed his head and his large ears.

In basic training at Ft. Sill, Okla., people knew Hill as the spindly, guarded kid who quoted Scripture and never cursed. One night he found himself on fire watch with another recruit, who began to cry and confessed that he was gay.

Stephen relaxes at home with his dogs Macho, a beagle-pug mix, and Gizmo, a boxer. Josh sent one of Macho’s chew toys to him in Iraq as a reminder of home.

Hill didn't know any gay people, but he knew they were definitely not tough enough for the U.S. Army, and so he said, sternly, "You can't be here." Soon after, the gay soldier was gone.

More than anything, Hill wanted to love women and have kids. He'd dated some girls, but had never kissed anyone with passion, nor experienced anything resembling romantic love. He believed in the Bible he carried, but it was also a good way to deflect questions.

"God, let me be normal," he prayed.

They made Hill an artilleryman in Desert Storm. From his armored truck, he sought out enemy positions and called in the coordinates.

Sometimes, he thought about how easy it would be if he stuck his head out of the truck and an enemy bullet just erased him. He'd be written up as a hero in the Daily Chief-Union, his hometown paper, and his parents would have no cause for shame.

One night, during the brief land war in February 1991, an artillery shell landed to his left, very close, and then another to his right, just as close. He braced for oblivion. When the danger passed, he thought, "I never would have loved anyone."

A few months later, as a freshman at Ohio State University, he listened intently to a speaker who claimed the power of prayer could help one surmount homosexual tendencies. He seethed. He had tried.

He sat outside a gay bar in downtown Columbus, watching people come and go, until he worked up the courage to enter. The bartender handed him a Diet Coke and touched the straw, which made him fear he might contract AIDS. He drank from the rim, head down, and left fast.

He came out to his parents, terrified of losing their love. His mother had sensed his distress and was relieved that it wasn't something worse. His father wondered if his son was under the influence of a campus cult. Then the former Marine said, "This is not a big deal," and embraced him.

One day, he argued with a boyfriend outside a coffee shop. A drunk called him a faggot and snarled a threat. He was accustomed to absorbing ugliness. But now he was a war veteran, trained in hand-to-hand combat, and this was a public street in a country he nearly died for.

He confronted the drunk and let him throw the first punch. Then he knocked him to the ground, pinned him face-down and pummeled his spine. It would have been easy to cripple or kill him. His friends blinked in shock. He walked away frightened of himself. He'd never allowed himself to hit someone in anger.

He got a master's in dietetics and went to work for the Columbus Public Health Department. He gave two weeks a year to the Army Reserve. When he showed up for duty, he tried to peel the pink triangle sticker off his car. He had to scrape it with his fingernails, strip by strip.

The Army drills were easy — by now he could out-run and out-lift many of his peers — but the loneliness was hard. He invented girlfriends and endured endless talk of the female anatomy. Every year, for two weeks, he encased himself in a shell to survive. "Like dipping myself in concrete," he would say.

He followed President Clinton's attempt to lift the ban on gay service members. One senator promised that this would "destroy the greatest Army that the world has ever known." The military brass spoke of the harm that would be done to the "cohesion" of combat units. Some warned of violence against gay soldiers.

The debate yielded "Don't Ask, Don't Tell," which was billed as a compromise but would result in the discharge of more than 14,000 gay service members over the next 18 years.

For Hill, it prolonged a double life of tension and hiding. The fortress of lies he'd constructed had to be ironclad. A soldier didn't have to broadcast that he was gay to lose his career. Someone noticing was enough.

Josh Snyder was instantly likeable, with an effortless smile and blue eyes that matched his own exactly.

He met him at a party in summer 2010, after nearly a decade of dead-end liaisons. Snyder was as outgoing as Hill was reserved. He worked for a big Columbus bank and wore dark, conservative suits.

Stephen and Josh Snyder-Hill walk hand-in-hand on a street in Columbus, Ohio. When Stephen left for Iraq in 2010, the couple had to hide under an airport escalator to say goodbye, while other soldiers were able to embrace their loved ones publicly.

He liked video games. Hill invited him over to play on the arcade-sized machine he had jury-rigged from spare parts. They spent hours tearing through the games of their childhood. Frogger, Pac-Man, Super Mario Bros.

There were innumerable tiny humiliations. At the Columbus fair, Hill spotted another soldier from his unit and yanked his hand from Snyder's grip. If anyone asked, they were brothers.

That summer, Hill learned his unit would be sent to Iraq by year's end. He would be gone 408 days. He knew deployments killed relationships, and he told Snyder that he wouldn't blame him if he wanted to break up.

At the airport, they watched soldiers embracing their families, saying goodbye. Hill and Snyder were hunkered under an escalator. "Like little rats, hiding," Hill would say.

He climbed on an airliner with 300 other soldiers. His life would be in their hands, in a land where many people wanted them dead.

"Don't Ask, Don't Tell" had been in the news again, as Congress debated its repeal. A jokester grabbed the intercom and announced the in-flight movie would be "Brokeback Mountain." The line provoked raucous laughs.

Hill's throat went dry. When the plane door closed, it felt like the shutting of a tomb, leaving him with "one of the sickest, emptiest feelings you can have."

"I can't do this. I can't do this," he sputtered over the phone when he landed. His voice had a desperation Snyder had never heard before.

A mattress, a TV, a broken chair. His tiny wooden room has the amenities of a cell, but affords more privacy than the communal tents. It smells of the duct tape he has plastered everywhere. It's a prison, but also a sanctuary, the place where he retreats to make secret phone calls.

He must survive a year at Contingency Operating Base Speicher, a makeshift city in northern Iraq encircled by concrete blast walls. His fellow soldiers know him as the spirited diet guru and fitness instructor who screams at them in the gym, a 40-year-old who can run harder and lift more weight than men half his age.

None of them knows.

He jogs amid the rubble of Saddam Hussein's reign. A bombed-out soccer stadium. A high diving board from which, he is told, one of Saddam's sons made people jump into a drained pool.

All day and night, through the plywood walls, he can hear choppers bringing the wounded from hundreds of miles around. Lying on his bunk, he looks at the flimsy ceiling and knows how easily an enemy mortar round could crash through it.

Snyder sends him a chew toy gnawed on by Macho, his beagle-pug mix. It reminds him of home. He sends him a Super Mario Bros. doll, which reminds him of their hours together. He sends him a handwritten love note, which bears his initials, J.S. If anyone asks, the J is for Jessica.

Snyder will text, "Are you free?" before initiating a conversation, just in case. Once, Hill's smartphone auto-corrects "I love you" as "Oliver," and that becomes their favorite word.

In these plywood quarters in Iraq, Stephen recorded the YouTube video in which he came out as gay with a question for presidential candidates. (Photo courtesy of Stephen Hill)

Sometimes mortar rounds hit the base while they are Skyping. Hill gropes for his flak vest, helmet and M-16, and scrambles to the concrete bunker, leaving Snyder blinking in panic at a blank screen.

Hill doesn't want to make him worry, so he leaves a lot out. He doesn't tell him about carrying the shrapnel-impaled victims of suicide bombings on a stretcher. Or having to collect the personal effects of a soldier who walked into a latrine and shot himself in the head.

Or trying to coax food into the mouth of one who had given up and was determined to starve himself to death. Or calculating the stomach-tube formula for another, whose .50-caliber rifle had accidentally blown off half his face.

Many mornings, Hill awakens to voice-mail messages from Snyder. He is careful to listen to them on a headset.

I love you. I miss you. You're one day closer to getting home. You're my hero.

He is home on leave in May 2011 when they decide to get married. Ohio will not perform the ceremony, so they drive to Washington, D.C. He returns to war wearing a titanium wedding band.

Jessica, he says. For his screensaver, he uses the image of a lesbian friend.

September 2011 should be a month for celebration. The military brass have retreated from their objections, and "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" is officially ending.

Maybe it is all the years of hiding and paranoia, but for Hill the victory feels like it could be snatched away in an instant. It is election season, President Obama looks vulnerable, and some Republican candidates have vowed to reinstate the policy if elected.

If that happens, he could lose his career. His uniform. His pension. His identity as a soldier. His honorable discharge. Everything.

He learns that Google and YouTube are hosting a nationally televised debate in Orlando, Fla., for the nine Republican presidential candidates. They are accepting questions.

He closes his door. He strips his name and rank from his uniform. He hides his face. He would like to disguise his voice, but he doesn't have the technology.

I am a gay soldier, and I am currently serving in Iraq, he says to the camera. The repeal of 'Don't Ask, Don't Tell' is going to be taking place in six days. Then it will be legal to say, 'I'm gay, and I'm here.' I wanted to know what the rights of gay people will be under a presidency of one of you, and if you'll try to repeal any progress that's been made for gay people in the military.

He sends it in and waits. YouTube likes his question, but they have a request. Could he please do it again without the "six days" line, so it won’t seem dated if it airs?

He closes his door. Instead of his combat fatigues, he wears a T-shirt that says ARMY. It is less official, he reasons, and therefore less likely to get him in trouble if he is discovered. It also displays his gigantic biceps, which he has not spent 20 years developing so he can hide them.

His face, he hides.

I'm a gay soldier and there's been a lot of progress made in the military with the abolishment of 'Don't Ask, Don't Tell.' My question is that under one of your presidencies would you try to change what's been made for progress for gay people in the military?

He sends it in and waits. Viewers are allowed to vote on potential questions, and he is informed that his question is a hit. But now YouTube has another, much scarier request:

Would you consider revealing your identity?

Hill doesn't need time to consider. There's no chance. He has too much to lose.

The Snyder-Hills work out in the basement of their home five times a week. Stephen holds a master’s degree in dietetics. As an Army diet and fitness instructor, he was known for his ability to out-run and out-lift men half his age.

Snyder reminds him that they are now married, and that it would not be hard for his command to discover this, and that if the ban is reinstated, he will be kicked out anyway.

He wakes for his 5 a.m. run. The blast walls seem closer than they were a week ago. The base is shrinking as America ends its nine-year occupation. He has survived his second war, and soon he will fly home, the same furtive, frightened man who arrived.

He thinks of the gay recruit he helped drive from the Army. He thinks of the drunk he might have killed. He thinks of how he clawed the pink sticker off his car. He thinks of hiding under the escalator.

In the subject line of his next email to YouTube, he writes: I have reconsidered.

On Sept. 22, 2011, Capt. Stephen Hill appears on the big screen at the Orange County Convention Center in Orlando, and on TV and computer screens across the world.

The camera is angled upward, revealing the features of the buzz-cut soldier. His muscles are almost comically swollen, bursting through the Army T-shirt. He speaks for 15 seconds. Midway through, his voice cracks.

In 2010, when I was deployed to Iraq, I had to lie about who I was because I'm a gay soldier and I didn't want to lose my job. My question is, under one of your presidencies, do you intend to circumvent the progress that's been made for gay and lesbian soldiers in the military?

There are boos. It might be only two or three people in the audience. But everyone will remember it.

Former U.S. Sen. Rick Santorum gets the question, and says, "Sexual activity has no place in the military." Allowing gays to serve openly "undermines" America's ability to defend itself. The crowd applauds enthusiastically.

Seven thousand miles away, before dawn in Iraq, Hill watches in his plywood box. It is not the booing that devastates him but Santorum's response, which frames the whole issue in terms of sex.

He turns off his TV. Because of the early hour, it is possible most of the soldiers have missed the debate. Somehow, he harbors the hope that he can escape with his anonymity and melt back into the ranks.

He lines up for breakfast in the chow hall. There are jumbo TVs mounted all over the walls. His face is on every one of them.

At a dinner speech, President Obama remarks on the Republican candidates' silence amid the boos: "You want to be Commander in Chief? You can start by standing up for the men and women who wear the uniform of the United States, even when it's not politically convenient."

On "Face the Nation," Sen. John McCain — who fought fiercely to keep "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" — says: "We should honor every man and woman who is serving in the military."

On "The Daily Show," Jon Stewart flashes an image of Hill and says: "If this guy turned into the Hulk, his arms would stay the same size. They would just turn green."

On HBO's "The Newsroom," a fictional news anchor says: "The only president on the stage last night was Stephen Hill. Godspeed, Captain Hill, and come home soon. A grateful nation is waiting to say thank you."

The C-17 transport idles on the tarmac, and Hill looks out the window at what is left of Contingency Operating Base Speicher. The PX and the gym have been shuttered, the shops with the bootleg DVDs boarded up.

He is going home. It is October 2011, just weeks after he asked his question.

Some soldiers told him they were surprised, some said they kind of suspected, and some confessed to leading their own secret lives. The initial awkwardness has been replaced, mostly, by a sense of exhilaration and possibility. He knows there must be soldiers mocking him, but the dynamic has shifted, and now they are the ones hiding.

Before boarding the plane, he empties his plywood hiding place and strips away all the duct tape. The light filters through the cracks into the empty shell.

Contact the reporter | Follow Christopher Goffard (@LATChrisGoffard) on Twitter

Contact the photographer | Follow Rick Loomis (@RickLoomis) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

About this story: This is one in a series of portraits of Iraq war veterans by Times staff writer Christopher Goffard and photographer Rick Loomis. All three articles, along with videos and photos, are at latimes.com/veterans.

Additional credits: Web Producers, Soo Oh and Evan Wagstaff

Also by Christopher Goffard and Rick Loomis