Exide’s troubled history: years of pollution violations but few penalties

For decades, inspectors from the California Department of Toxic Substances Control dutifully recorded a long list of environmental infractions at the Vernon battery recycling facility now owned by Exide Technologies.

They described fluid gushing from a wastewater treatment system 10 years ago. They saw battery acid flowing into a manhole, lead waste stored in open containers and enormous cracks in flooring meant to contain hazardous chemical spills. Year after year, state inspectors documented illegal activity during annual walk-throughs at the 15-acre plant about five miles southeast of downtown L.A.

Yet, it wasn't until Wednesday that the Georgia-based company faced serious consequences. Under a deal with the U.S. attorney's office, Exide admitted to nearly two decades of illegal activity and agreed to permanently close, demolish and clean up the facility — and remove lead from surrounding homes — to avoid prosecution.

A Los Angeles Times review of two decades of enforcement records shows the state Department of Toxic Substances Control knew for years that Exide was violating environmental laws by spewing contaminants into the air, soil and water but only recently began taking steps to stop it.

• The department levied only seven fines on Exide and the plant's previous operators over 20 years, despite logging dozens of serious infractions, often for the same recurring offenses.

Numerous violations, few fines

Since 1996, state inspectors have documented violations every year at the battery recycling plant in Vernon. Exide Technologies and its predecessor, GNB, have paid slightly more than $1 million in fines during that period. Click on a row to view the inspection reports for that year. View all reports here.

• Over more than 15 years, Exide paid $869,000 in penalties. Most were assessed in the last two years after public outcry over revelations that the facility's arsenic emissions posed an increased cancer risk to 110,000 residents.

• The department only used its strongest enforcement tools after outrage over air pollution boiled over in 2013. It did not refer the violations at Exide for criminal prosecution until federal officials began investigating last year. Instead, regulators relied on negotiated orders and settlement agreements that company documents refer to as "consensual resolutions."

The federal investigation that led to Exide's closure relied on evidence provided by the DTSC that spanned decades, and for 33 years the agency allowed the facility to operate with only a temporary permit.

That history has led critics to raise questions about why it wasn't shut down sooner, whether the state toxics department is adequately overseeing other hazardous-waste operations and whether it is up to the task of ensuring Exide cleans up its mess.

Exide's agreement with the Department of Justice allows it to resolve a criminal investigation that, under the conditions of its Chapter 11 bankruptcy, would have led to the company's liquidation and left taxpayers with the multimillion-dollar cleanup bill.

Exide declined to comment for this story.

Testing has shown that decades of pollution from the plant has left the Vernon site and surrounding areas so heavily contaminated that they will take years and at least $50 million to clean.

Amid calls for reform from lawmakers, the department's relatively new director, Barbara Lee, has acknowledged the agency's past oversight was inadequate. But she said that she told Exide in February it would be denied a full permit and that she had been negotiating a closure plan for weeks. Lee promised that the department will force Exide to pay to clean both pollution at its site and lead contamination in hundreds of nearby homes.

"The Department's enforcement record for many years at Exide does not in any way resemble how I expect my enforcement program to perform," Lee said in an emailed statement. "It's unacceptable and I am changing it."

Terry Gonzalez-Cano and her family have lived about a mile from Exide in Boyle Heights for four generations, and she believes it has damaged their health. "Everything that they found in this investigation was happening years ago," she said. "So why did they have to wait so long?"

Problems at nearly every inspection

The battery recycling facility now owned by Exide opened in Vernon in 1922. It is one of only two lead-acid battery recycling plants west of the Rocky Mountains. Exide Technologies acquired it in 2000, when it was operating under a temporary permit the state granted in 1981. Violations by its predecessor, GNB, continued under Exide's watch.

"I've lived here 31 years and we were never advised, never given any health notice that we were so close to such a toxic situation," said Msgr. John Moretta, pastor of Resurrection Catholic Church in Boyle Heights. When Exide's excessive lead and arsenic pollution was made public several years ago, he and his parishioners began organizing to shut down the plant.

Smelters that recycle car batteries are heavily regulated because they release dangerous pollutants such as lead and cancer-causing arsenic. Lead is a powerful poison that can cause developmental problems and lower IQs in children, even at low levels.

The DTSC's oversight of Exide is detailed in thousands of pages of enforcement records The Times obtained under the California Public Records Act.

State inspections, conducted at least once a year, found lead and acid leaks, an overflowing pond containing toxic sludge and lead dust that had rained down on to nearby soil, streets and businesses.

The state recorded problems at nearly every inspection. Some citations were minor. But many were Class I violations, the type the department says require enforcement action because they present "significant threat to human health or safety or the environment."

Inspectors in 2013 found leaking trailers storing hazardous lead-acid battery waste, which Exide admitted in its agreement last week with federal prosecutors was a felony. Inspectors also found hazardous levels of lead on a street outside the plant and in the soil in the employee parking lot. But it wasn't the first time.

In 2008, the department sampled roofs of neighboring businesses and the street and soil outside Exide and discovered lead concentrations of up 52,000 parts per million — more than 50 times the regulatory limit for hazardous waste. DTSC deemed it an "immediate" threat and ordered cleanup measures.

State inspectors reported violations at Exide even after stricter air-quality regulations forced the operation to go idle a year ago. Inspectors noted new problems, including holes in the facility's walls and roof, as recently as January.

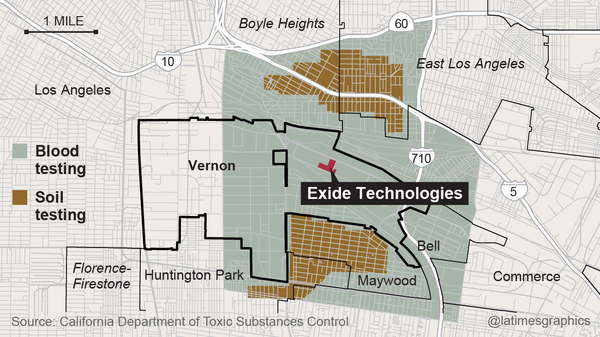

Department officials said that since 2013 their inspections, enforcement actions and penalties against Exide increased dramatically. The agency hired new staff and required blood and soil tests in communities near the facility. So far, all but three of more than 100 homes in Boyle Heights and Maywood that have been tested for lead have shown levels above allowable limits, the DTSC said. As a result, a few dozen homes have been cleaned up.

"Exide's facility will be properly, permanently closed, and its contamination in the community cleaned up," said Lee, who took over as director of the department in December. "And Exide will pay for it."

But for years, the state struggled to force the company and its predecessor to comply with orders. In 2013, the DTSC ordered Exide to shut down because of its arsenic emissions and a degraded stormwater piping system, but the company successfully challenged the directive in court.

Measuring the health risks

Residents near the Exide Technologies battery recycling plant in Vernon are eligible to have their blood tested for lead poisoning. The soil at more than 250 nearby homes is being tested for lead contamination.

In an agreement with the state last fall, Exide agreed to pay its largest penalty yet, more than $526,000, and to set aside $38.6 million for closure, along with $9 million in a trust fund to clean lead-tainted soil from surrounding homes. A closure agreement the state announced Thursday expedites those payments and requires the company to devote $5 million more for residential cleanup.

A new state law had compelled the toxics department to either grant Exide full permission to operate this year or force it to shut down.

Among other reasons for its recent decision to deny the company a permit, the DTSC cited its "failure to certify the structural integrity of a containment building used to hold hundreds of tons of lead, and poor history of compliance with environmental and health protection laws," including 10 enforcement actions against the facility since 1990 that cited more than 100 violations of California's hazardous-waste laws.

"Moving forward we have been doing the right thing to protect public health and the environment," said Elise Rothschild, who heads the department's hazardous-waste management program.

Questions about the future

Residents in the working-class, Latino communities near Exide had for years asserted that activities there were illegal and harmful to their health. They want to know why the facility wasn't shut down five, 10 or 20 years ago.

News of the plant's closure has renewed calls from advocacy groups and lawmakers for overhauling California's toxics department. Previous Times investigations have reported on an array of problems in the agency, including flaws in its tracking of hazardous-waste shipments, slow responses to urgent environmental threats and a backlog of expired permits for hazardous-waste operations.

California Senate leader Kevin de León (D-Los Angeles) said regulators had collected more than enough evidence to shut down Exide years ago.

De León said that if the department fails to properly oversee the cleanup of Exide, "we will move forward with legislation to dismantle that agency and rebuild it from the ground up."

In previous interviews, Exide officials have said they worked to comply with state regulations and spent millions upgrading pollution controls. A company statement issued Thursday said, "Exide expects to be able to meet its closure and cleanup obligations."

The company is facing several lawsuits over its pollution, including one on behalf of children who live near the plant and another from the region's air-quality agency.

Sean Hecht, an environmental law professor at UCLA, said it takes large penalties and strong enforcement to force companies like Exide to fix pollution and waste violations.

"In this case, neither one happened: The penalties weren't high enough to make a difference and DTSC never pushed the company hard enough to make sure fundamental problems were fixed," said Hecht, who eight years ago raised concerns about the facility's history to the department.

Gonzalez-Cano, 42, said years ago she joined with other parishioners at Resurrection Catholic Church who were worried about the health effects of pollution from the facility and urged state regulators to crack down.

"Still nothing was done," she said.

She believes her family has paid the price for that inaction.

She and her 10-year-old son, 25-year-old daughter and her brother suffer from an array of illnesses, including asthma, skin cancer and learning disabilities. They want to know the extent to which emissions from Exide are responsible.

They're still waiting for answers.

Twitter: @tonybarboza

For continued and full coverage, go here.

Additional Credits: Video: Spencer Bakalar and Bethany Mollenkof. Graphics: Thomas Suh Lauder. Web Developer: Honest Charley Bodkin.