Finding Marlowe

I

t was hot and I was late for lunch. I was feeling mean, like I’d been left out in the sun too long.

We were meeting at a joint on La Brea, the kind of place where the booths have curtains you can pull shut if you need a little privacy. I slid across cool leather and got my first good look at Louise Ransil, a wisp of a redhead with high cheekbones and appraising eyes.

She sat with her hands folded on the worn table, a stack of old paperbacks next to her.

Ransil had a script she’d been peddling to the studios. I’d started reading it — a detective caper set in 1930s Los Angeles — and wanted to find out about the claim on the title page.

“BASED ON A TRUE STORY: From case files of P.I. Samuel B. Marlowe.”

Watch a behind-the-scenes video with Daniel Miller and Louise Ransil »

Ransil didn’t waste any time.

Marlowe, she said, was the city’s first licensed black private detective. He shadowed lives, took care of secrets, knew his way around Tinseltown. Ransil dropped the names of some Hollywood heavies — Clark Gable, Jean Harlow, Howard Hughes.

But it got better. Marlowe knew hard-boiled writers Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett, she said.

The private eye had written them after reading their early stories in the pulp magazine Black Mask to say their fictional gumshoes were doing it all wrong. They began writing regularly, or so her story went. The authors relied on Marlowe for writing advice, and in the case of Chandler, some real-life detective work.

So his name was Samuel Marlowe … and their most famous characters were Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe.

That was no accident, she was sure of it.

Maybe, maybe not. At the very least, it was a hell of a coincidence.

But the letters that would prove it all had gone missing — if they even existed.

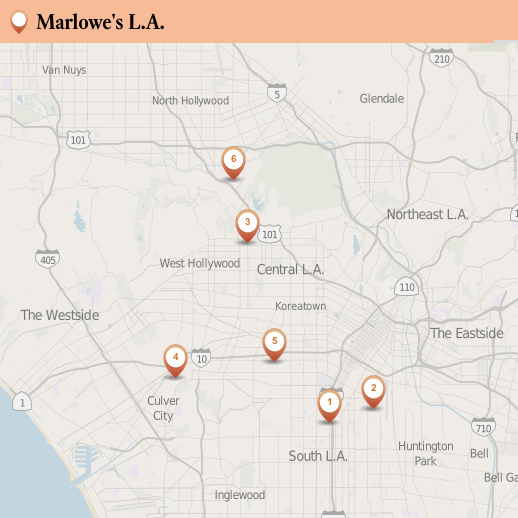

Marlowe’s relatives were searching for them. There was talk of a secret compartment in a home in West Adams. Or maybe they were hidden at a shuttered thrift shop in South Los Angeles.

Ransil flashed a wry smile. Was I interested?

Lost letters worth thousands. A family trying to uncover the truth about a man all mixed up in the glamour and the seediness of L.A. between the wars. And a Hollywood screenwriter who stood to gain a lot from any story I might write.

This was L.A. noir.

I didn’t know if I could trust Ransil, a former executive with Orion Pictures and New Line Cinema who lived alone in a penthouse with a pet parrot.

But she had gotten to me. Chandler and Hammett created two characters that shaped the archetype of the noir detective as a world-weary white man, and she was saying they might have been named after a black private eye.

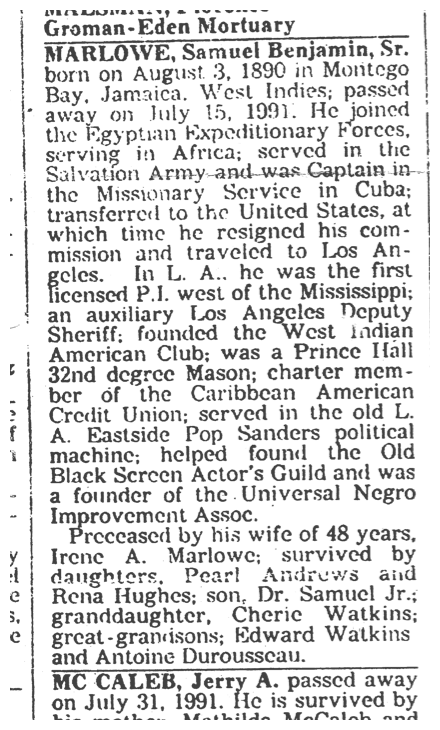

I started checking out Ransil’s story, looking up the paid obituaries in The Times and the Los Angeles Sentinel from when Marlowe died in 1991.

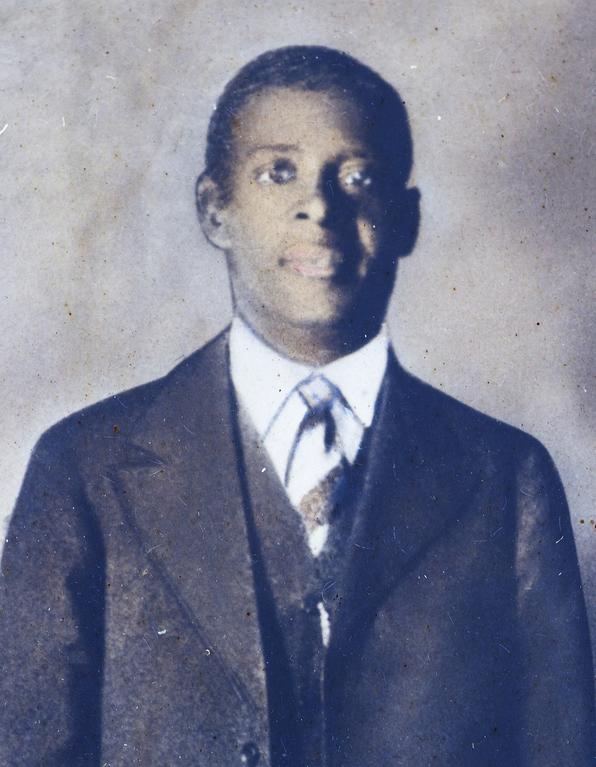

Marlowe was born Aug. 3, 1890, in Montego Bay, Jamaica. According to The Times obituary, he served in Britain’s Egyptian Expeditionary Force, a World War I fighting brigade that guarded the Suez Canal. After the war, Marlowe immigrated to the U.S., settling in Los Angeles, where he soon became a private detective.

Both obituaries made the same bold — and almost certainly untrue — claim: “In L.A., he was the first licensed P.I. west of the Mississippi.”

The notices were larded up with the private eye’s civic achievements, even referencing a few organizations — like the Old Black Screen Actor’s Guild, from his days as a bit actor — that I couldn’t verify ever existed.

I needed to turn to Marlowe’s family members. And to Ransil.

She said that after reading the obituaries, she reached out to the gumshoe’s son, Samuel Marlowe Jr., who gave her access to his father’s archives.

Over the course of several months in 1991 and 1992, Ransil said, she examined the PI’s papers at the younger Marlowe’s home — rifling through old case files, invoices and correspondence — and took notes in Stenoscript shorthand. She showed me dozens of pages of them.

Ransil said she didn’t photocopy anything because it would have amounted to hours of work and she figured there’d be plenty of time to examine it all. She eventually set aside the project, distracted by her day jobs. By the time she picked it up again in 2006, Marlowe Jr. was dead.

Ransil, 61, acknowledged that doubters could say she’s playing fast and loose with the truth to score a movie deal. She’s adamant that her motives are pure.

At least Ransil wasn’t the only person who claimed to have seen the letters.

Willie Rawls, 74, a Marlowe family friend, said she examined them around 2001 just before they went missing. And one of Marlowe’s great-grandsons, Antoine Durousseau, said he saw them too.

“A lot of them were handwritten — letters between Marlowe and the authors,” he said. “Marlowe kept a pretty good file cabinet.”

More on the shuttered shop that housed some of Marlowe’s possessions »

I followed a lead to a big man drenched in sweat. He was picking through battered steamer trunks and moldy cardboard boxes.

John Cummings was searching for the lost letters — or anything else that could prove the man he knew as a boy was a trusted advisor to two literary lions.

“He had a gold-capped tooth right here,” Cummings said of his great-grandfather, pointing at one of his own front teeth, “and was addicted to cigars, horses and women.”

As the sun beat down on a dilapidated South L.A. building, Cummings, 48, took a break. He wasn’t satisfied with the objects he’d unearthed at the property, once a thrift shop operated by his late father, who had retrieved some of Marlowe’s personal effects when the private eye died.

For Cummings, it’s personal. He wants to prove what a 1980s story in the Sentinel asserted: When Marlowe became a PI in 1921, he was the “first black man to have a licensed detective agency in the state of California.”

“I am more interested in Sr.’s legacy, and the legacy of African American men who have blazed a trail and gone unrecognized,” said Cummings, speaking in a cigar-ravaged rasp.

The California Department of Consumer Affairs, which issues private detective licenses, has no record of Marlowe, but an agency spokesman said that older files are often incomplete or missing. USC history department researcher Angelica Stoddard, whose work centers on L.A.’s first licensed black private eyes, says Marlowe is the earliest one she’s heard of.

Cummings ducked into a rusty white Ford Econoline van parked out back and emerged with a heavy cardboard box. He set it on the ground and plunged his hand in, pulling out a pistol, bullets, stale cigars. There was an address book with an entry for Universal Studios’ payroll department and a placard that read, “This property is protected by the Samuel B. Marlowe Detective Agency.”

I started re-reading Chandler’s and Hammett’s novels, gulping down their stories of crooks and femmes fatales, dizzy with all that hard language coursing through my head.

Hammett’s debut novel, “Red Harvest,” was published in 1929 — the same year Marlowe wrote the author to complain about his writing, Ransil said.

The following year, Hammett released “The Maltese Falcon,” with its iconic, white private detective, Sam Spade.

Marlowe claimed that Spade’s first name was an homage to him, and that the character’s surname was Hammett’s “winking inside joke,” because “spade” was a derogatory term for a black person, Marlowe Jr. told Ransil.

In 1933, Hammett published “Nightshade,” a little-known, four-page tale that appeared in Mystery League magazine and is his only work to feature a black protagonist.

In the story, the lead character, Jack Bye, helps a blond out of a jam with two toughs. Afterward, they visit an African American speak-easy called Mack’s.

Once she leaves, the barman tells Bye: “I like you, boy, but you got to remember it don’t make no difference how light your skin is or how many colleges you went to, you’re still a n—.”

Ransil said that Marlowe’s cache of letters from Hammett included a carbon copy of a draft of “Nightshade” with an index card clipped to it suggesting the story was inspired by the private eye:

“I came across this and thought you might like to have it. You’ll see I changed a few of the details, but I think it still works.”

Marlowe, family members say, provided security for illegal speak-easies during the Prohibition era, when Hollywood types liked to frequent the Dunbar Hotel and other nightspots on South L.A.’s Central Avenue — long the center of African American life in Los Angeles.

Great-grandson Durousseau said that he’d been told by older relatives that film studios also paid the gumshoe to “pick up actors and actresses who were in the wrong part of town at speak-easies and juke joints.”

The work on Central Avenue, and a walk-on part in the 1933 epic “King Kong,” introduced Marlowe to a slew of movie industry players. Among those who relied on Marlowe were Howard Hughes and Charlie Chaplin — both of whom used him to keep tabs on women they were seeing, Ransil said.

In 1936, Paramount Pictures hired Marlowe to investigate an attempt to blackmail actress Marlene Dietrich, Ransil’s notes show. Marlowe went to a train station to stake out the delivery of $8,000 in hush money provided by the studio to a “young man.” He turned out to be the son of Dietrich’s makeup artist.

“Dietrich refused to have the makeup woman and son arrested because she and the makeup woman had been lovers,” Ransil’s notes show.

The detective also started doing a little work for Chandler after the author wrote the PI asking if he could retrieve some police files, Ransil said. Marlowe’s billing files, she said, show that he was also Chandler’s guide on research expeditions to the “tough parts of town.”

Marlowe gave Chandler a bit of advice on how to think like a PI: “Believe no one, even the person hiring you — especially the person hiring you,” according to Ransil’s notes.

In 1939, Chandler released “The Big Sleep,” his first Philip Marlowe novel. It turned the writer into a literary star.

Chandler followed up “The Big Sleep” a year later with “Farewell, My Lovely,” considered by some to be his greatest work. Ransil believes that the South L.A. vignette that opens the book depicts a side of the city that Chandler would have been unfamiliar with unless he had a guide like Marlowe.

The novel opens on Chandler’s Philip Marlowe emerging from a barbershop on Central Avenue. He watches the felon Moose Malloy throw a black man out of a bar called Florian’s. Later, Malloy and Marlowe come across an African American bouncer at Florian’s who says, “No white folks, brother. Jes’ fo’ the colored people. I’se sorry.”

“Where did he get that? Why Central Avenue?” asked Judith Freeman, author of the biography “The Long Embrace: Raymond Chandler and the Woman He Loved.”

The research institutions that house the two writers’ papers said none mention Marlowe. And scholars have plenty of other ideas about where the characters’ names might have come from. Freeman said the connection would be plausible — “if one could find even the smallest direct link.”

I thundered down the 110 toward Compton, my coupe shuddering over the highway’s tar-smeared seams. I was hoping for an audience with Marlowe’s oldest living relative — his nephew.

Samuel Joseph Marlowe lives in a pink, wood-sided house with a security gate at the front door. It was a Sunday, and down the block a church was flooded with parishioners who spilled out onto a porch.

I parked across the street, where two steely-eyed men sitting in a late-model sedan clocked me as I hustled up the driveway. My visit was unannounced; I’d had a mind to doorstep Samuel Joseph, who didn’t answer my letters or have a working phone.

Inside I found a withered man lolling deep in a stained couch, as comfortable as an old shoe.

His speech had been muddied by a recent stroke, but Samuel Joseph, 88, was eager to talk.

He spoke of his journey from Jamaica to Los Angeles in 1947 and how his uncle got him a job at a cold storage facility. Marlowe was willing to lend a helping hand, but when Samuel Joseph needed help filing his taxes, the flinty PI charged him $10.

“When he finished my income tax I went by the house and he said, ‘Your paperwork is finished,’ so I reached up to get it,” Samuel Joseph said. “He said, ‘You can pay me $10 first.’ I picked it up anyway. He pulled out his little pistol and said, ‘No, you put it back until I get my money.’ He was joking, but he was meaning it too. He didn’t pity no man.”

Samuel Joseph smiled at the story but told me that he didn’t know about Marlowe’s connection to the writers. He said in a bashful sort of way that I knew more about his uncle than he did.

“Oh, what should I say about Uncle Sam?” he trailed off, squinting at something unseen.

I had hit another dead end.

Marlowe kept things close to the vest, even with his relatives. But as he grew older, he hinted at his glory years, back when he called himself the “Answer Man.”

Durousseau remembers watching television with Marlowe years after he’d retired. The old man’s eyes lighted up when the film adaptation of “The Maltese Falcon” came on the screen.

Watching Humphrey Bogart hunt down the jewel-encrusted falcon statuette, the elderly former detective gestured at the television and said “he knew that guy from the movie,” Durousseau recalled.

The private eye died two weeks before his 101st birthday. He’s buried at the Inglewood Park Cemetery. I visited with Durousseau and watched as he cleaned the grave marker in row 1190 of the cemetery’s Resthaven section, sluicing it with water from a fast-food restaurant cup.

“He outlived his family members, he’d seen Los Angeles [transform] from nothing to everything,” said Durousseau, 44, stifling tears. “He just felt he was ready to go.”

After the detective died, some of his possessions were transferred to his son’s house in West Adams. The old Dutch Colonial became the focus of a family legal battle when Marlowe Jr. died in 2003, and that may have led to the loss of the private eye’s files.

After three years of legal skirmishing, the house was put on the market — and the feuding heirs never retrieved the files from it. When buyer Ethan Polk toured the property before making an offer, it was filled with the belongings of the late PI and his son. As part of the transaction, Polk stipulated that it be cleaned out.

“The real estate agent hired a crew of people to clean out the house,” Polk said. “They basically dumped everything.”

It had been a year of hard work but even harder luck when I met Ransil for lunch again, this time at an Italian place on Hillhurst Avenue. She appeared more frail than I’d remembered.

As I walked in, the faint sound of an army of air conditioners registering their protests set me on edge. We were in the middle of a ferocious heat wave and AC units had been surrendering all across the city.

Ransil ordered a tuna melt with fried potatoes and picked at the food. I barely gave her time to eat.

I peppered her with questions, asking again why she hadn’t photocopied Marlowe’s files. I told her about the real estate agent’s crew, and what they’d done.

I needed a good night’s sleep, I needed a change of scenery, and I needed a break in the case. It didn’t look like any were coming.

Ransil slumped back into the green leather booth. She said she felt ashamed that she’d let the story slip through her fingers.

“It's a long and twisted tale that didn't turn out the way I’d hoped,” she said. “I'm kicking myself in a lot of ways.”

There was another lead to pursue, and I wasn’t some soft-boned flatheel who’d give up without a fight.

The Dutch Colonial once owned by Marlowe’s son is a husk, shedding roof shingles and sloughing off its white clapboard exterior. But it could hold the private detective’s secrets.

Word is, the house contains at least one hidden compartment where the younger Marlowe had stashed valuables. Ransil said that the private eye’s daughter, Rena Hughes, once told her about this. A former resident, Stacie Ottley, recalled one in a bedroom too.

“There’s a room that had a little thing in the floor,” Ottley said. “One of the floorboards moved.”

Could the letters still be there? I asked Polk, the current owner, if he’d mind if I tore up a room. He gave me a look and, laughing a little, agreed.

I called up my handyman, a street-smart Cincinnatian named Dan Boster who keeps his salt-and-pepper hair short. I asked for a favor. A week later, the two of us stooped in one of the house’s closets. Boster yanked up musty carpet. He rapped his fingers on the hardwood floor.

A hollow thump.

Sweating now, he leaned in and edged a steel scraper between two boards. The wood gave way. Cool air rose from below. I swallowed and looked down.

Nothing.

I’d spent a year chasing dead men. They weren’t talking. Maybe they never would.

But I just got another tip. I’m in too deep to quit now.

Twitter: @danielnmiller

Contact Daniel Miller | Illustrations by Morgan Schweitzer | Photography by Gina Ferazzi | Design and production by Armand Emamdjomeh and Lily Mihalik